Jet Crashes and Hidden Treasure

In 2019 Digby was contracted to search for the crash site of a USAF jet, piloted by Forrest Fenn, that was shot down over Laos in 1968. Forrest Fenn is famous in the USA for writing a cryptic poem that started a massive treasure hunt for a bronze chest containing gold and artifacts worth some $2 million that he hid somewhere in the Rocky Mountains.

Litter 81 Found

By Chris LaFrieda, PhD

Photographs by Digby Greenhalgh and Kai Chang

Introduction by Forrest Fenn

Christopher LaFrieda is a treasure hunter by hobby and a designer and maker of microchips when he is not thinking about WWWH (‘where warm waters halt’ – a clue used to find the treasure). His PhD is in electrical engineering. He was studying my life looking for clues when he became interested in my Vietnam experience, especially the story about me being shot down. Before my mind could catch up with what he was doing, he was looking for my crashed F-100, deep in the Laotian Jungle. Yeah Chris, good luck with that one. This is his story. f

It’s still morning here in New Jersey, but it’s just past 11 p.m. in Laos. I should have heard from Digby and Kai by now. Communicating with my team in Sepon has been a constant struggle. There’s only a small window of time to arrange a call before they turn in for the night, exhausted from the long day spent in the extreme heat and humidity of the Laotian jungle. If that fails, then there’s an eight-hour wait to try again in their a.m. Today is different though.

This was our last shot to find the wreckage of a missing Vietnam-era warplane, an F-100D with serial number 55-3647. The pilot, who safely ejected and was rescued by helicopter over 50 years ago, is home in Santa Fe, New Mexico eagerly awaiting news of its fate. We’ve been growing increasingly confident about finding it over the past few days. I wouldn’t know how to break it to him if we are unsuccessful. I’m also starting to worry about my guys.

The United States dropped approximately 300 million bombs on Laos during the Vietnam War. About a third of those never went off and they continue to maim and kill to this day. The area around Sepon, where we are operating, is one of the most contaminated in all of Laos. Local guides will try to steer my team around unexploded ordnance, but much of it is hidden beneath the surface and you wouldn’t know it’s there until it’s too late. Oh, then there are the tigers.

Kai translates, “The boy says he saw a footprint the size of an open hand. That means the tiger is as big as a water buffalo.” They seemed to feel better when one of the guides offered to bring his AK-47 with them into the jungle. That only made me more nervous. The locals say not to bother worrying about tigers because the giant poisonous centipedes are the real danger. How did I get myself into this mess?

You may have heard that there is a treasure chest filled with gold hidden somewhere in the Rocky Mountains. In 2010, Forrest Fenn hid the chest with the hope that it would motivate people to “get off the couch” and experience nature. Forrest wrote a poem that contains clues to the location of the treasure and published it in his memoir, The Thrill of the Chase. In addition to the poem, Forrest teases that his memoir contains “subtle clues” hidden among its stories.

After nearly a decade, nobody has found the treasure. That’s just the sort of challenge that I can’t resist, so last year I picked up a copy of Forrest’s memoir. Its stories cover 80 years of Forrest’s life from his first steps at the beginning of the Great Depression right up to the time he hid the treasure. All the stories are fascinating, but one perfectly sums up Forrest’s special brand of luck and adventure—his rescue after being shot down as a fighter pilot during the Vietnam War.

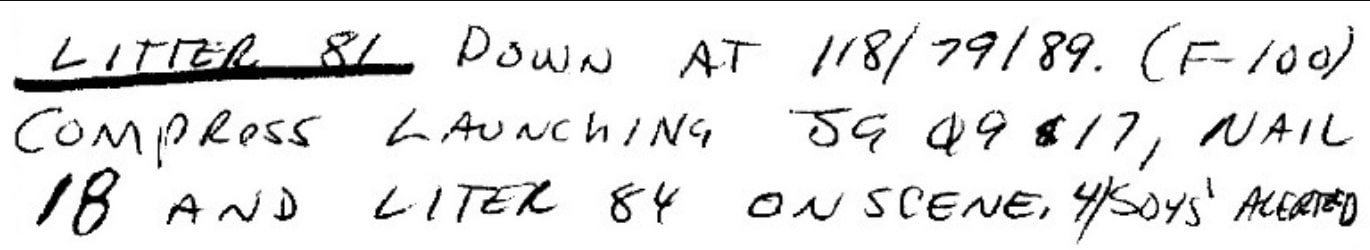

On December 20, 1968, Major Fenn was leading a flight of four F-100Ds under the call sign Litter 81. As part of Operation Commando Hunt, their mission was to drop ordnance on the main road leading into Tchepone, Laos (now known as Sepon) to disrupt the movement of North Vietnamese troops and equipment along the Ho Chi Minh Trail. As Forrest made his passes over the target, his F-100 was hit and severely damaged by anti-aircraft fire. Rather than immediately heading for safe ground, Forrest charged the guns and marked them as targets for the rest of his flight (an act that earned him the Silver Star).

Forrest pulled away from the guns and, as instructed, took a heading of 030 for bailout. His plane held together long enough to get him to a remote stretch of jungle, about 20 miles away from the action, before he ejected. As Forrest descended in his parachute, he watched his F-100 crash into a distant cliff and explode in a giant fireball. After spending a harrowing night in the jungle and narrowly avoiding capture, his Forward Air Controller (FAC), James Swisher, found him the next morning and alerted rescue forces.

One Crown C-130, two Jolly Green HH-3Es, two Misty F-100Fs, four Sandy A-1s, and one Nail O-2 with a total crew of 26 all worked quickly to rescue the downed pilot. The Jolly Green helicopters, one low and one high (a backup), took their positions over Forrest, hoisted him out of the jungle, and ferried him safely to their base at Nakhon Phanom, Thailand. As was typical for the time, Forrest was given just a few moments for a photo op and to thank some of his rescuers before they all continued with the business of war. Forrest had the distinction of being the 1,500th combat save in Southeast Asia.

There was something about the rescue that puzzled me. Forrest was out of radio contact with his flight and rescue forces for about 14 hours. A cursory study of rescue operations from that era suggested that was an anomaly. Usually, a doomed aircraft would be escorted by a wingman through bailout. The wingman would then orbit near the downed pilot until rescue forces arrived, while maintaining constant radio contact with the survivor. In Forrest’s case, he had somehow been separated from the rest of his group and lost, then found the next day. There had to be more to this story.

With the help of a retired Air Force historian, George Cully, I obtained mission reports from each of the units involved in the rescue. The full picture started coming into focus, but there were details that I would only learn after tracking down James Swisher, the FAC who found Forrest.

Wisher explained, “We [the FACs] were given a heading of 300 for bailouts in the morning briefing. Forrest ended up on a heading of 030, 90 degrees off. He punched up through a break in the clouds and we lost sight of him.” (It’s not clear where the incorrect heading came from, but Swisher’s account makes sense because 030 is toward North Vietnam.) Swisher assumed Forrest turned to 300 and they spent the first day looking for him in the wrong place. Early the next morning, Swisher returned with a pair of Misty F-100s (same plane as Forrest) and sent them along Forrest’s last known trajectory. When they cleared the mountains that were blocking Forrest’s transmissions, he came up on the radio.

In April I visited Forrest at his home in Santa Fe to discuss these newly found details about his rescue. Forrest sang my praises, “Chris is a ferret. I was looking for Swisher for 50 years and he found him in two weeks.” (It was closer to two months.) We spent the next couple of days poring over his collection of Vietnam memorabilia, which included a handwritten log of every mission he flew, his parachute beeper, combat maps, photo albums and letters. The pièce de résistance was a photograph taken by Roger Gibson, the co-pilot of the backup chopper, just as Forrest was being hoisted up out of the jungle.

At first glance, the photo appears to show only a lush green jungle surround by magnificent stone cliffs. Upon careful inspection, a tiny, camouflaged helicopter can be seen nestled in the treetops. As Forrest held the photograph, he told me that in the 1970s, a filmmaker wanted to bring him back to Laos to find the wreckage of his airplane. “I was going to find the flight stick from my F-100 and bring it home. That would have been some trophy.” Forrest raised his hand slightly and closed his eyes as if he could see himself holding that piece of his airplane. For a moment, I thought I could see it too.

The project eventually fell through and it was clear that the passing decades did little to assuage Forrest’s disappointment. Forrest continued to regale me with stories about his tour in Vietnam, but my mind kept drifting back to the thought of finding his airplane. Fifty years had passed. Could it still be out there? I was confident that with the rescue photo and mission reports, I could find the exact spot where Forrest was pulled from the jungle. However, Forrest was the only person to see where his plane crashed. If there was any chance to find it, we’d have to rely on half-century-old memories to get us the rest of the way.

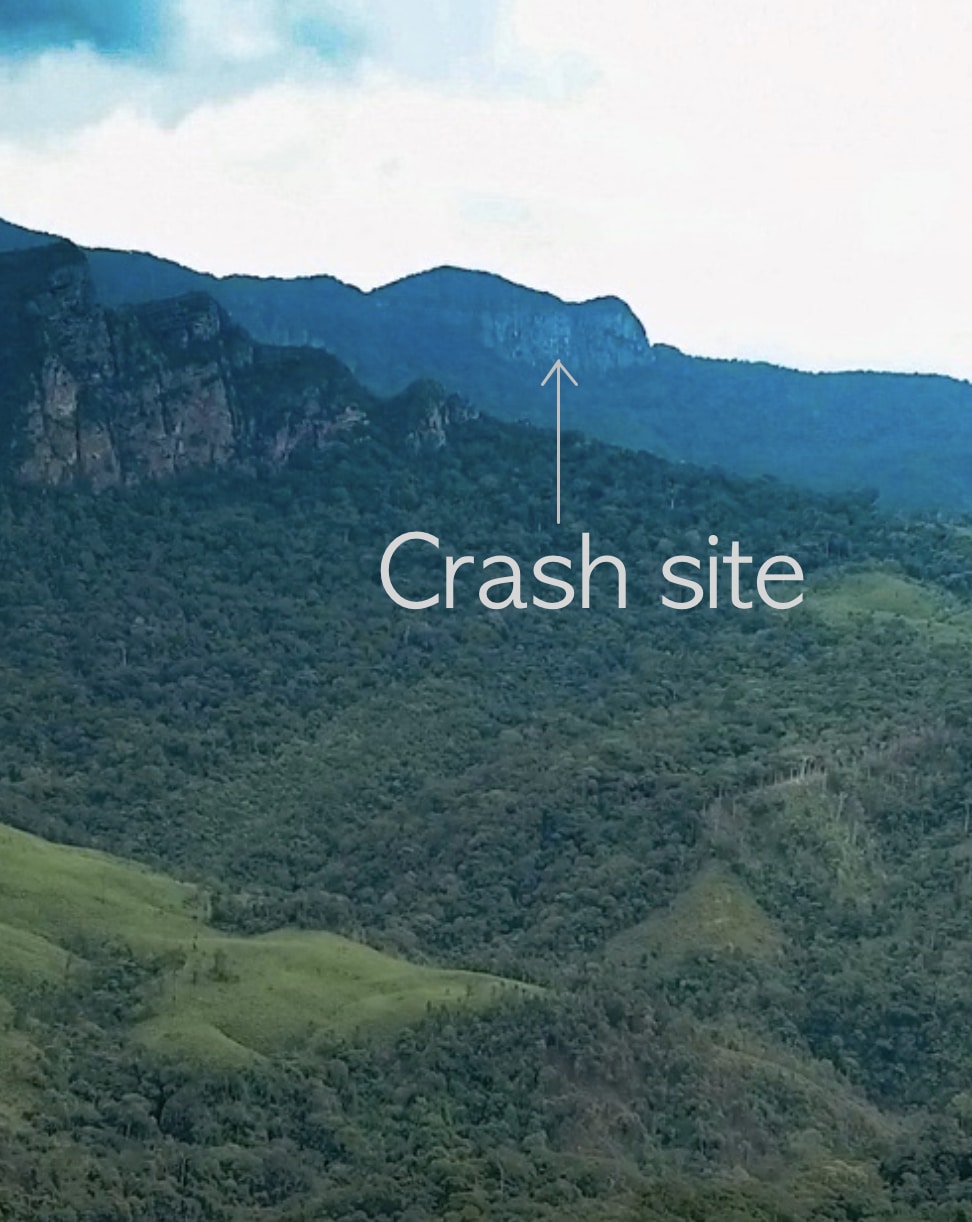

Over the next few weeks, I peppered Forrest with questions about his bailout. I did my best to disguise my intentions because I didn’t want to be the second person to get his hopes up and then shatter them. Forrest was able to recall that he was flying parallel to a cliff wall and that his plane crashed halfway up a distant cliff wall, approximately one minute after ejection. That reduced the search area to a series of cliffs about 3-4 miles from the extraction point. There was still too much ground to cover, so I tried to press him further. That’s when Forrest said, “If I was 500 feet above where my chute is hanging in the trees, I could point to where the plane crashed.” I suspect that was Forrest’s polite way of changing the subject, but it gave me an idea.

At age 88, Forrest wasn’t going to travel to Laos and fly around in a helicopter looking for wreckage. Fortunately, technology could provide an alternative. Forrest’s extraction point is roughly 13 miles north of Sepon, Laos on lands that belong to the Village of Ban Talouay. Satellite images show a clearing in the jungle about 1 mile east from the extraction point. If we can get permission from the village and if we could make it to the clearing, then we could send up a drone, get footage from Forrest’s parachute perspective, show it to Forrest and, hopefully, get a fix on the crash site. That’s a lot of ifs, and there really was no we yet, but the idea was technically sound.

I needed to assemble a team that included a translator, drone pilot and local guides. Due to the remoteness and rugged terrain of the area, it seemed logical to enlist the help of a travel agency that specializes in motorcycle tours of Laos. I reached out to James Barbush, an American expat living in Laos, and explained the situation. James runs Remote Asia Travel with his wife Quynh, and he personally has years of off-roading experience at remote locations in Laos, including near Sepon. James would serve as a one-stop shop of sorts. He recruited the required personnel, handled the equipment rentals, made the travel arrangements, and applied for all the necessary permits. The only caveat was that rainy season had just begun, and they’d have to wait for a break in the weather to proceed. The short delay gave me an opportunity to become acquainted with my team.

Kai Chang would act as translator and guide for this expedition. Kai is Laotian and speaks both Lao and English fluently. He’s worked for James as a motorcycle tour guide for over five years and led many weeks-long tours across the rough backroads of Laos. Over the years, Kai has developed contacts at many of the remote Laotian villages, including Ban Talouay.

Digby Greenhalgh is our drone pilot. Originally from Australia, Digby has lived in Hanoi for almost two decades. His company, Explore Indochina, provides motorcycle adventure tours across Laos and Vietnam. He has been exploring the Ho Chi Minh Trail by motorcycle for the past 17 years and has ridden the trail over 25 times. Digby has been featured on several television shows, including The World’s Most Dangerous Roads and Top Gear. More recently, Digby has been using drones to explore parts of the trail that are too dangerous to get to on foot.

After weeks of daily thunderstorms, the weather improved marginally to intermittent rain. It was decision time. James advised, “Go for it. Wait it out in Sepon and hit your weather windows as you can.” Digby seemed to concur, “The only way to know will be to stick our hands out the window in Sepon.” I brought Forrest up to speed and asked him to be ready to review the drone footage. Slightly stunned, he responded, “This is exciting, Chris. I’ll do what I can.” There was no backing out now. We were a go.

On the morning of June 11, Digby and Kai departed from Vientiane on motorcycle. The 400-mile trek to Ban Talouay was impeded by poor road conditions and the occasional downpour. They arrived at the village the following day and arranged a meeting with the naiban (village chief). Armed with a photograph of Forrest, Kai, speaking in Lao, relayed the story of Forrest’s rescue and his desire to find the remains of his missing F-100. The naiban was sympathetic. Not only did he grant access to their lands, but he also arranged for three hunters from a neighbouring village to serve as guides. Their chat was followed by friendly carousing and storytelling into the night.

The naiban has lived in the village his entire life. During the Vietnam War, when he was just a boy, the village was moved farther up into the valley, not far from where Forrest spent the night in the jungle. The naiban revealed that there were Vietnamese bases throughout the area—a fact that underscored how fortunate Forrest was to escape capture. The North Vietnamese fed and looked after the villagers, and in return the villagers helped them. After being on opposite sides of such a brutal and devastating war, the naiban had readily offered us his assistance. In a way, I felt this expedition was already a success.

Early the next day, Kai and Digby regrouped at the naiban’s house for a quick introduction to their guides, Su, Noob and Don. The five men crowded onto three motorcycles and started up the dirt road at the west side of the village. The rocky narrow road cuts a swath through an overgrown jungle that occasionally blocks out the sky above them. They followed the road over streams and rain-filled depressions, passing through a bamboo gate, and eventually reaching its end at a dry creek bed, about 3 miles into the valley. They parked their bikes and continued on foot.

Over the next half mile, the creek bed turns into a stream, then into a full-fledged gorge with sheer stone walls as it squeezes between two mountains. The crew navigated the meandering path as the rocks beneath their feet grew from stones to boulders. Just past the narrowest section of gorge, the grade quickly lessens and the stone walls crumble, yielding to the jungle environment. The guides escorted the group up a steep trail to a hilltop clearing.

The clearing offers a unique 360-degree view of the entire jungle valley, which is surrounded by a C-shaped mountain range with 1,000-foot-high stone bluffs. Waist-high and shoulder-high crops with long narrow stalks cover sections of the clearing. Digby inquired, “Kai, can you ask the guys what they planted here?” Kai translated, “They say the tall plants are exported to China or Vietnam to make fiber for clothes. The smaller one, the people use it to make a roof for their house.” The guides further explained that the villagers cleared out the trees just two years ago. Prior to that, our expedition wouldn’t have been possible.

Digby laid out his equipment and prepped the drone for launch. The cliffs in the rescue photo perfectly matched the cliffs to the west of their position; Digby knew exactly where he needed to go. He piloted the drone a mile out to precisely where Forrest broke through the jungle canopy, climbed to 500 feet and scanned the mountains on the far side. With the remaining battery, Digby made a pass along the western side of the bluffs and then hightailed it back to the clearing. He checked the drone footage and made an exciting discovery.

From what seems to have been Forrest’s vantage point during bailout, the surrounding terrain masks all but one 700-foot-long section of distant cliffs—it was the only place that fit his description of the crash site. Digby signalled for the guides to come over and pointed out the location on a map. They became animated and started talking over each other. Kai summarized, “They sometimes go up there to hunt. There are plane parts along the base of that cliff. They say that is where the plane crashed.”

This crash site is one of several nearby sites that are known to the villagers. They normally don’t advertise the locations of these sites, but they felt compelled to after we made the connection. Over the years, these sites were stripped of most of their metal to support construction booms in Vietnam and China. Only small fragments or non-metallic items remain. The guides cautioned that the three-hour hike to the crash site would be difficult, but they were willing to take Kai out there the next day. Kai agreed and the group retraced their steps back to Ban Talouay.

That night, back at the hotel, Digby updated Forrest and me on the recent developments and sent us some drone footage to review. Forrest confirmed, “That is exactly as I remember it.” We planned to have Kai take two cell phones to the crash site and photograph every piece of wreckage with emphasis on anything with a serial number. We scheduled a call for 9 p.m. the following night. Kai should be back before then. That gave me a day to figure out how to identify an airplane from small parts.

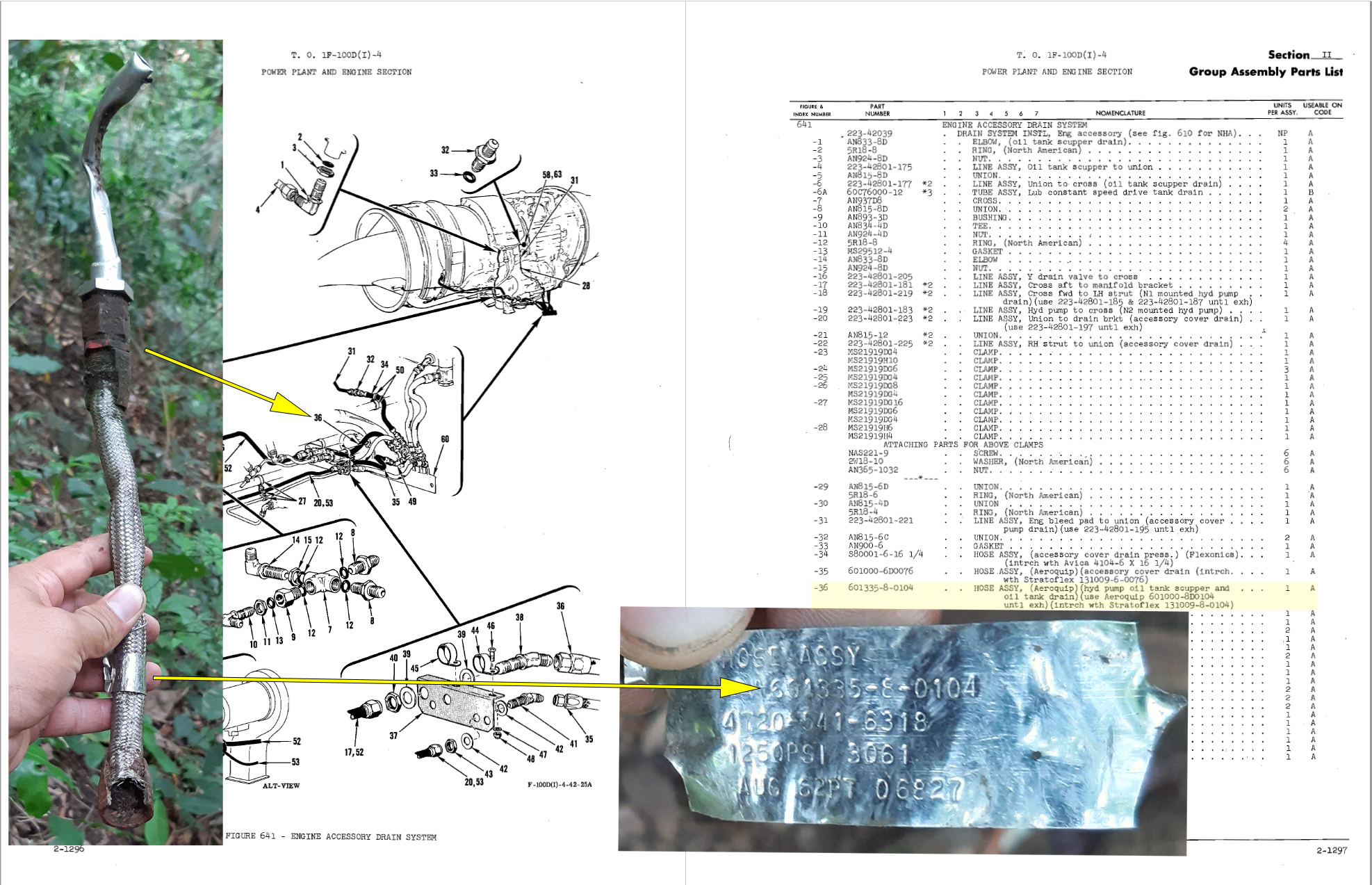

Fortunately, the National Archives hosts a database of all aircraft losses during the Vietnam War with their last known coordinates. Those records show that 183 planes were lost within 30 miles of the crash site. Only four of those planes, including Forrest’s, were F-100s. Forrest ejected 3 miles from the crash site. The other F-100s were reported to have crashed or exploded at least 15 miles away. If the wreckage is from an F-100, then there would be no doubt that we found Forrest’s plane.

In my collection of F-100 materials, I had a copy of a technical manual named Illustrated Parts Breakdown. That manual contains a complete list of the F-100’s more than 30,000 parts. If we find any serial numbers belonging to an F-100, they’ll be in there. I placed the manual next to the phone on my desk. I was ready. All I could do now was wait.

A little after 11 p.m. Laos time, the phone rings.

“Mr. Chris” a voice beams with an Australian accent that I’ve become accustomed to. “Yes, Mr. Digby,” I returned, sensing the incoming good news. “Tell Forrest to break out the bubbly, we found Litter 81.” An elated Digby and Kai recount the events of that day…

That morning, Kai rendezvoused with the guides at Ban Talouay and, this time, they rode off on the trail at the northern side of the village. Near the end of the trail, they ditched the bikes and headed northeast into the jungle on a barely visible footpath. After a short walk, the jungle opens at a hidden rice paddy packed with green shoots and dotted with burnt tree stumps, a by-product of slash-and-burn. They continued along a stream at the northern end of the paddy.

The stream grows in size and intensity as they near its source—a small waterfall flowing over a stone ledge and into a pool of clear water. The last mile of the journey is a steep 1,300-foot climb up the mountain. Stone slabs form a natural staircase and exposed roots act as handholds to aid the group as they ascend. After an exhausting two-hour climb, they reached a relatively flat tree-covered ridge at the base of 1,000-foot-high stone cliffs.

Various jet debris found at the crash site

On the return trip, the guides stopped to bathe in the pool at the small waterfall before returning to the village. Ban Talouay was alive with singing and dancing. Neighbouring villages had joined in the festivities and they were feasting on a large pig that was spit roasted over an open fire. It was a wedding! Kai said his goodbyes to our new friends and made his way back to the hotel.

As I listened to the story, I felt an adrenaline rush come over me. It quickly turned to panic as I began to worry: What if we found the wrong plane? I needed to research those plane parts ASAP.

The tire fragments are from a Goodyear size 3.0 x 8.8 tire with a ply rating of 22. They match only one type of aircraft with losses in Laos, the F-100. Hose assembly #601335-8-0104 is from the hydraulic oil pump attached to the F-100 engine. Similarly, all the other identifiable parts are a match to the F-100. We did it. We found Litter 81.

Weeks later, a package arrived. I can’t say how, but a small piece of aluminium, vibrating with the spirit of Litter 81, made its way down the mountain and travelled halfway around the world to get to me. I padded a small wooden box, placed the metal bit inside, closed the lid and shipped it to Santa Fe. Shortly after, I received an email from Forrest:

“You are an absolute genius. That fragment is so beautiful. Words cannot describe how I feel about this little thing, Chris. It is a real part of me now. Thank you so much.”

– Forrest

Postscript

Forrest Fenn’s treasure was finally found on June 6, 2020. Three months later, Fenn died at age 90.

Videos:

Digby and Kai at the drone take off clearing

Drone footage to rescue extraction site (no audio)

Hike to crash site / wreckage