Motorcyclist Magazine

Riding the Ho Chi Minh Trail

by Digby Greenhalgh

Riding the Ho Chi Minh Trail

I was standing on the crumbling remains of a former top-secret air base deep in the mountains of Laos that was once used by America in its secret war against Laotian and Vietnamese communists. Instead of Huey helicopters, CIA agents and US pilots dressed as civilians however, now only a terrible mix of Britney Spears cover songs kept the local people focused on their dance moves as they shimmied over the tarmac. It was the wedding season, and no one was interested in that conflict anymore. Nor did they care that they were dancing on what was once the second busiest airport in the world, where every day planes loaded with bombs made their way southwards to take out the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

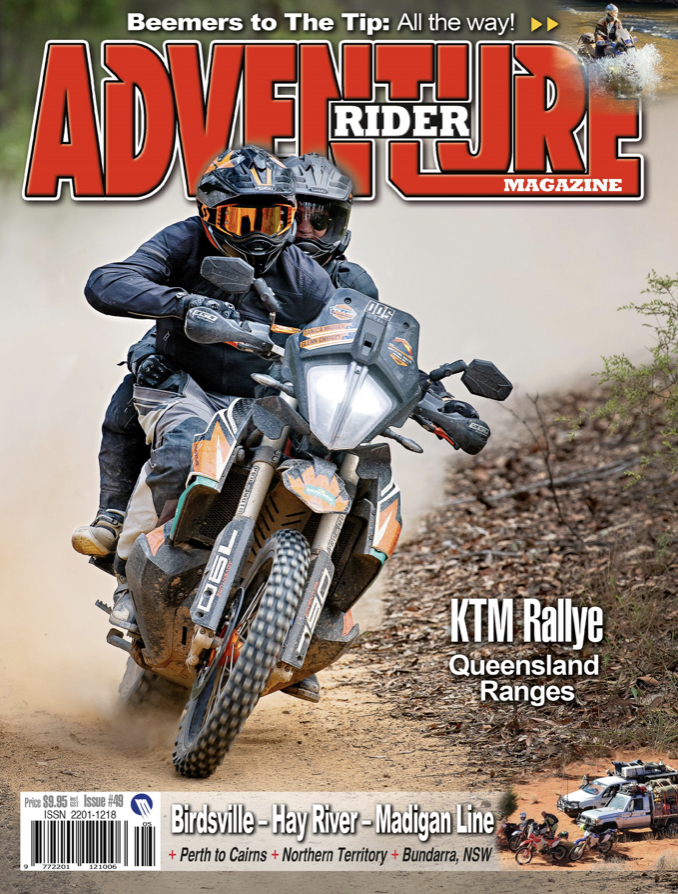

Keeping the Trail open during the 60’s and 70’s was therefore a matter of life and death for North Vietnam’s war effort in South Vietnam. If the US had shut it down then the strategic balance would have shifted in its favour. Thus tens of thousands of Vietnamese road construction/repair teams, thousands of trucks and porters and hundreds of anti-aircraft guns bore the brunt of a ferocious, yet secret, US bombing campaign. Most of the Trail ran through the mountains and forest of neutral Laos, which due to the Geneva Convention was a political no go area for America. Nevertheless, Presidents Johnson and Nixon ordered such extensive bombing that close to 600,000 combat missions were directed against this tiny nation. Put another way, a US plane dropped its payload of bombs every eight minutes, around the clock, 24/7, for a staggering nine years!

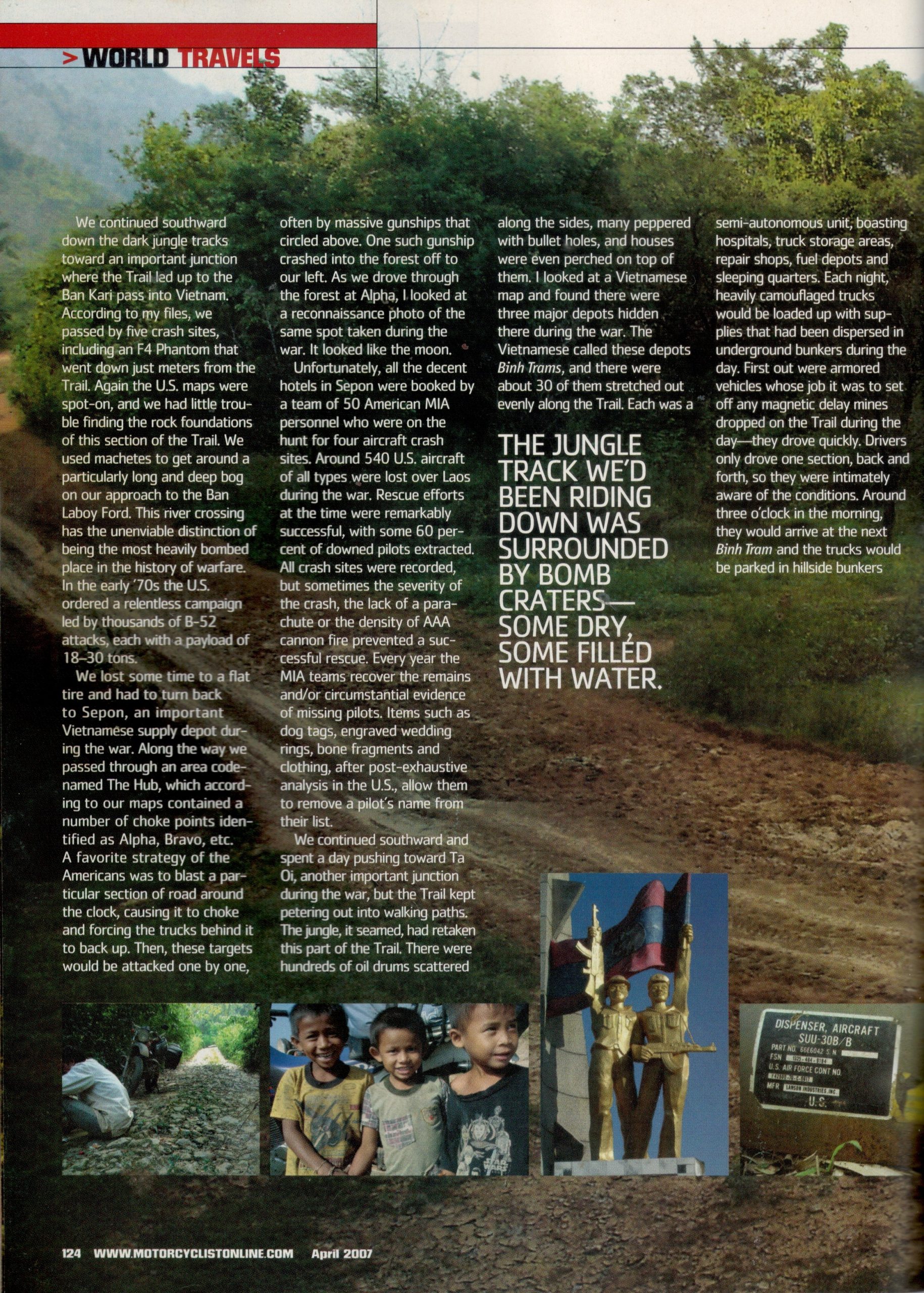

Little wonder then that the jungle track I had been driving down was surrounded by bomb craters, some dry, some filled with water, even after forty years. Meanwhile, villages contained simple wooden houses perched on top of bomb casing and spring onion patches grew in upturned cluster bomb casings. There were even bombs just lying on the sides of the road, and on one large river, boats were actually made from massive jettisoned aircraft fuel tanks that have been cut in half.

Unexploded Ordnance

We were taking no chances, and stuck to the dirt track at all times. People still die every year due to unexploded cluster bombs, the size of tennis balls. During the war some 80 million cluster bombs were dropped on Lao, and now some eight million remain unexploded. Four boys earlier that day had shown us a number of broken pieces they had found with an improvised metal detector. They will earn US$3 for the 30 kilos of rusting shrapnel they collected that day, and once a month a Vietnamese truck will visit all the local scrap yards in that area and load up around 25 tones. Considering more bombs were dropped on Laos than the entire Allied effort in WWII, it is little wonder that forty years on, the Vietnam War still leaves its mark.

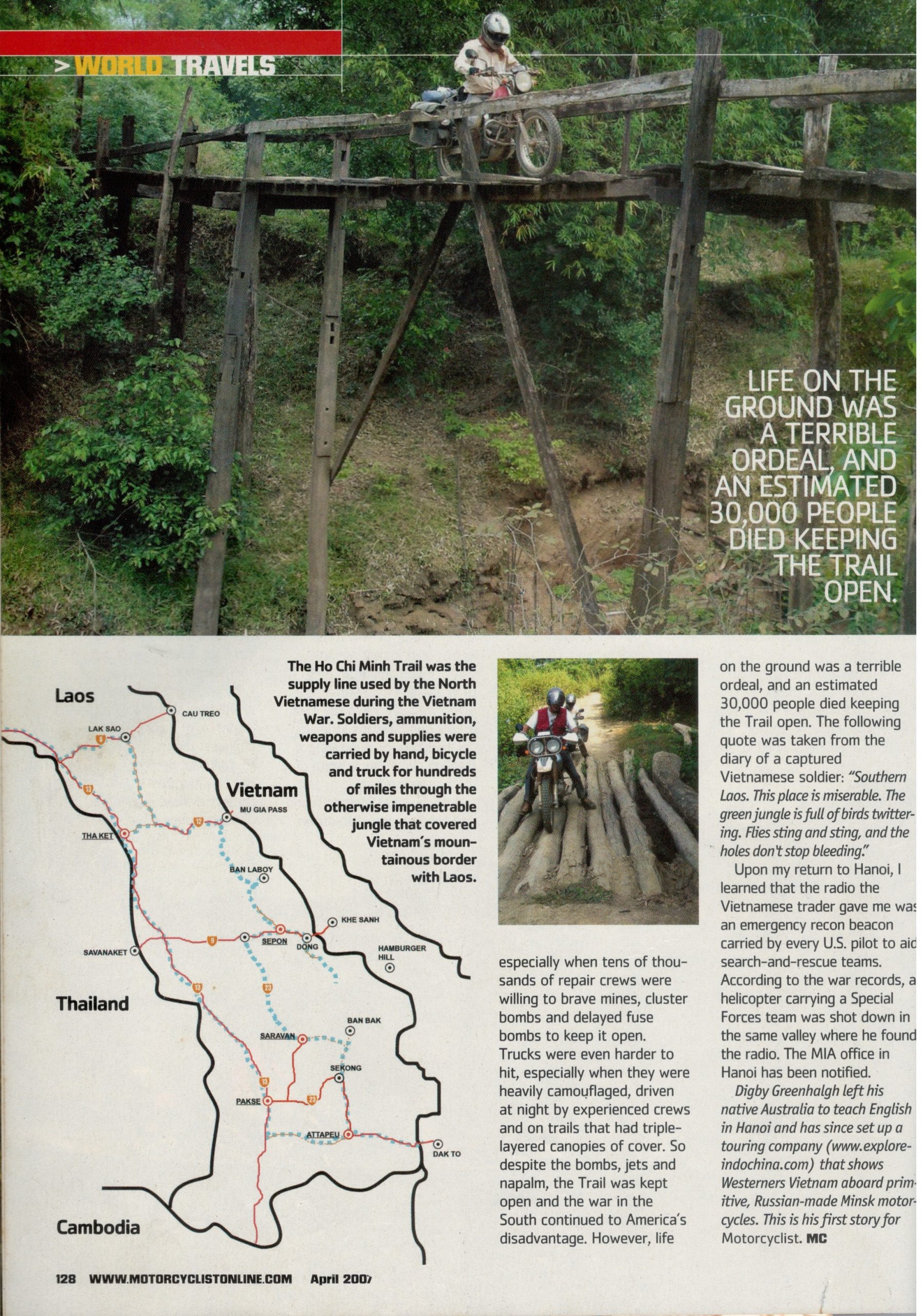

The jungle track forked in two and we were not sure which way to go. During the war there were thousands of such junctions and turns that allowed the Vietnamese trucks and porters to bypass heavily bombed areas. All told, the Trail was a network which contained more than 3,500km worth of motorable roads. We consulted a US army map used during the war by forward air controllers, who flew single propeller Cessna “Bird Dogs” low in the sky in an effort to map the Trail, spot targets and direct attack runs by other planes. They had a pretty good idea exactly where the main arteries of the Trail were, and with the aid of a GPS, we followed their lead and took the right fork down to a river crossing. There we waited for a snake to swim to the other side before driving through water up to our waste. Once on the other side we realized we had chosen correctly, as underfoot were the original paving stones first laid down by the Vietnamese road teams, almost 40 years ago. We were back on the Trail!

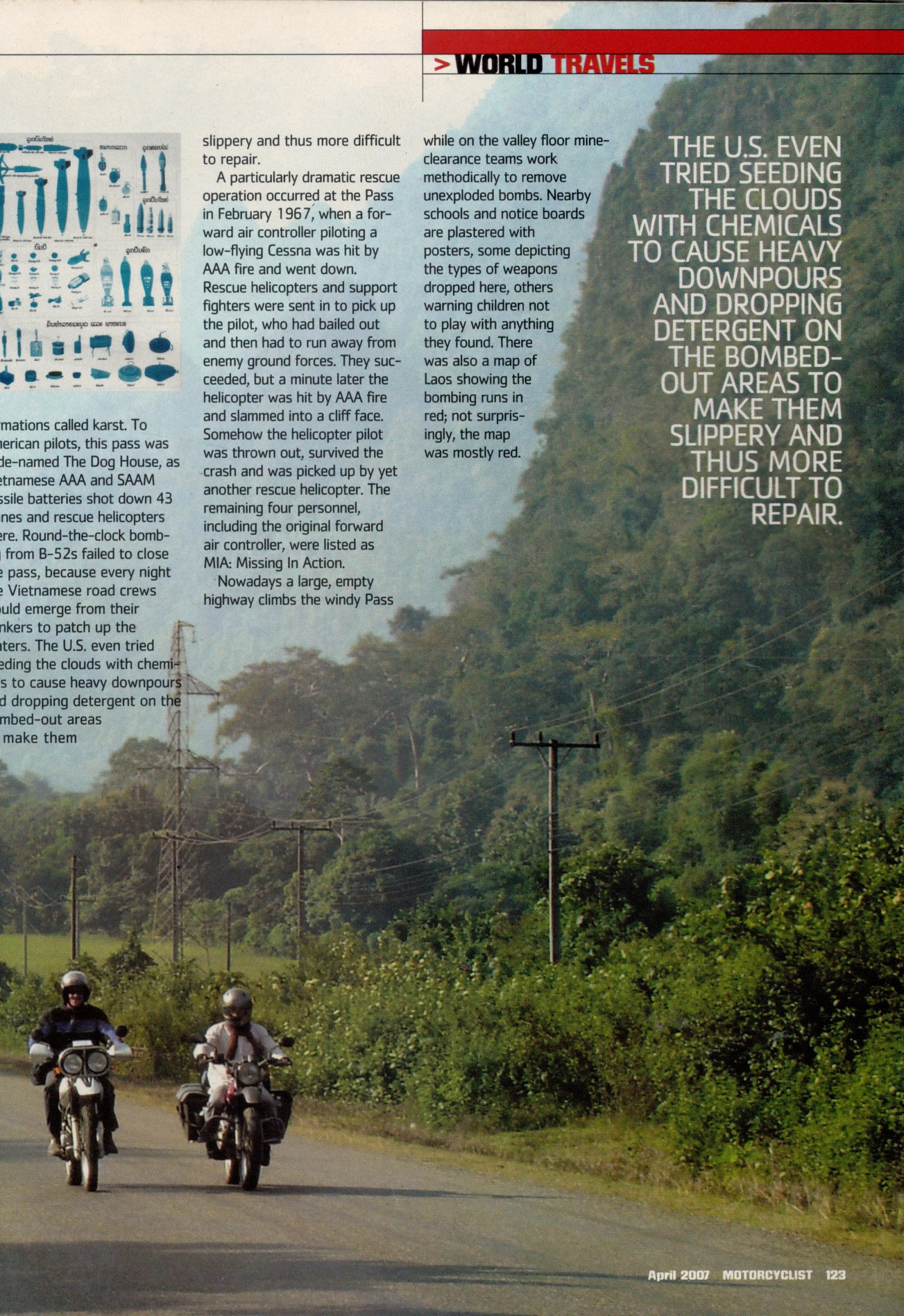

The Mu Gia Pass

Our two week adventure started at the Mu Gia pass, a dramatic slot valley that cuts through the otherwise impenetrable Truong Son mountain range which runs along the border of Laos and Vietnam. This valley is one of the only ways to get into Laos from Vietnam as the mountains there are plugged full of very rugged limestone rock formations called karst. To American pilots this pass was code named the “Dog House”, as Vietnamese AAA and SAAM missile batteries shot down 43 planes and rescue helicopters there. Round the clock bombing from B52s failed to close the pass, because every night Vietnamese road repair teams would emerge from their bunkers to patch up the craters. The US even tried seeding the clouds with chemicals to cause heavier downfalls while another operation saw detergents dropped into the bombed out areas in order to make them slippery and un-repairable.

A particularly dramatic rescue operation occurred there in February, 1967 when a forward air controller piloting a low flying Cessna was hit by AAA fire and went down just near the top of the pass. Having bailed out into the jungle, rescue helicopters and support fighters were sent in to pick up the pilot, who had to run away from enemy ground forces. They succeeded but a minute later the helicopter was hit by heavy AAA fire and it slammed into a cliff face. Somehow the helicopter pilot was thrown out just before impact, survived the crash and was picked up by another rescue helicopter. The remaining four personnel, including the original forward air controller, were listed as MIA.

Nowadays a large empty highway climbs the windy pass while in the valley floor mine clearance teams work methodically to remove unexploded bombs. Nearby schools and notice boards had many warning posters. Some showed the kinds of weapons dropped here, some warned children not to play with anything they found while another was a map of Laos with the bombing runs marked on it in red, which not surprisingly, was mostly red.

Finding the Radio

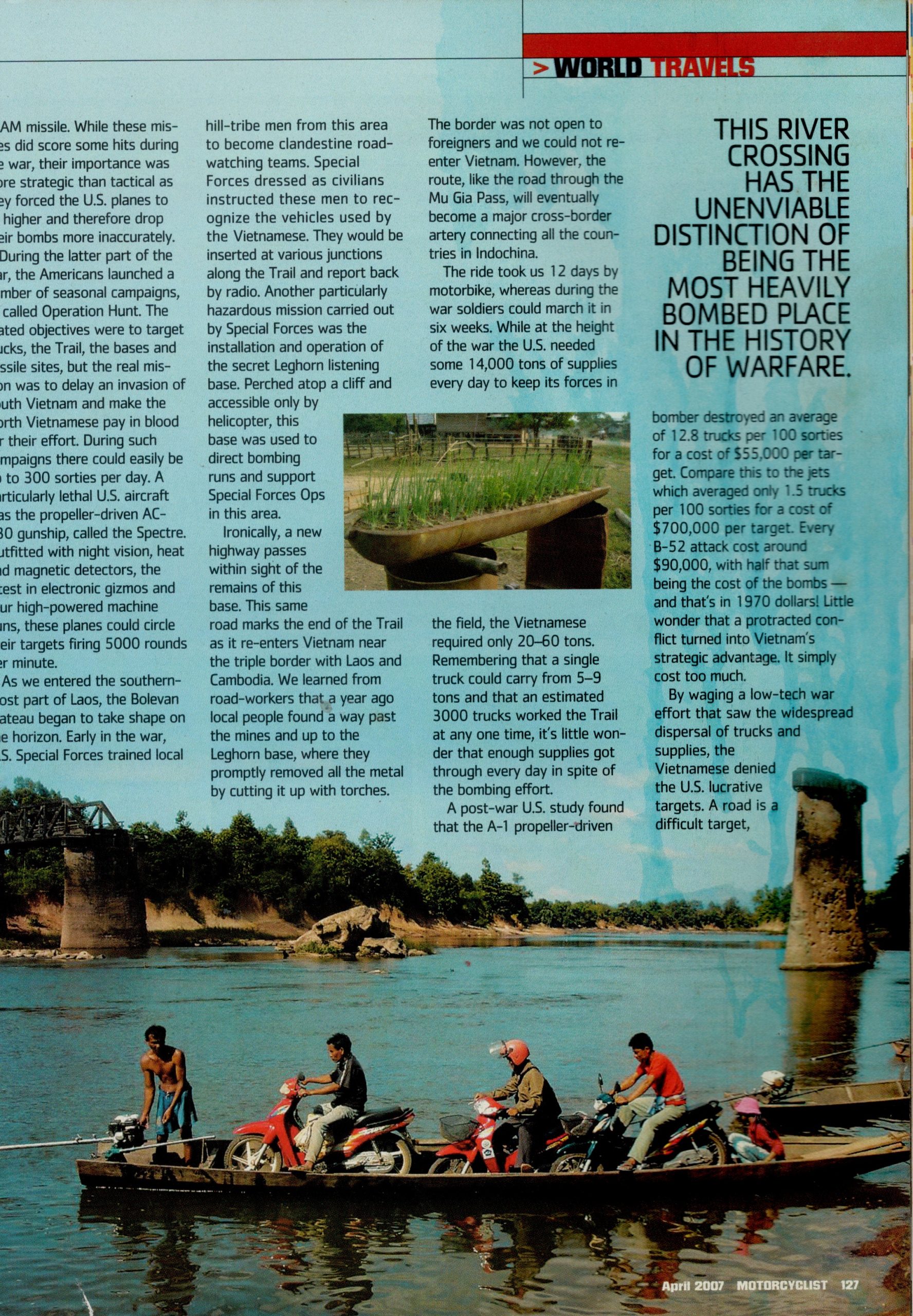

We continued southwards down dark jungle tracks from Mu Gia pass towards an important junction where the Trail led up to the Ban Kari pass into Vietnam. According to my files we passed nearby to five crash sites, including a F4 Phantom that went down just meters from the Trail. Again the US maps were spot on and we had little trouble finding the rock foundations of this section of the Trail. We used machetes to get around a particularly long and deep bog on our approach to the Ban Laboy ford. This river crossing has the unenviable distinction of being the most heavily bombed place in the history of warfare. In the early 70’s the US ordered a relentless campaign led by thousands of B-52 attacks, each with a payload of 18-30 tones.

We lost some time to a flat tire and had to turn back to Sepon, an important Vietnamese supply depot during the war. Along the way we passed through an area code named “The Hub”, in which, according to our pilot maps, contained a number of choke points code named “Alpha”, “Bravo” etc. A favored strategy by the Americans was to blast a particular section of road around the clock, causing it to choke forcing the trucks behind it to backup. Then these targets would be attacked one by one, often by massive gun ships that circled above. One such gunship crashed into the forest off to our left. As we drove through the forest at Alpha, I looked at a reconnaissance photo taken during the war of the same spot. It looked like the moon.

Unfortunately all the decent hotels in Sepon were fully booked out by a team of 50 American MIA (Missing in Action) personal who were on the hunt for four aircraft crash sites. Around 540 US aircraft of all types were lost over Laos during the war. Rescue efforts at the time were remarkably successful, and some 60 per cent of downed pilots were extracted. All crash sites were recorded but sometimes the severity of the crash, the lack of a parachute or the density of AAA cannon fire prevented a successful rescue. Every year the MIA teams recover the remains and or circumstantial evidence of the missing pilots like dog tags, engraved wedding rings, bone fragments and clothing that, post exhaustive analysis in the US, allow them to remove a pilot’s name from the MIA to the KIA list.

We continued southwards and spent a day pushing tracks towards Ta Oi, another important junction during the war, which unfortunately always petered out into walking paths. The jungle, it seamed, had retaken this part of the Trail. There were hundreds of oil drums scattered along the sides of the Trail, and houses were even perched up on them. Many were peppered with bullet holes. I looked at a Vietnamese map of the Trail and found that there were three major depots hidden there during the war. The Vietnamese called these depots “Binh Trams’ and there were about 30 stretched out evenly along the Trail. Each was a semi-autonomous unit, boasting hospitals, truck storage areas, repair shops, fuel depots and sleeping quarters. Each night the heavily camouflaged trucks would be loaded up with supplies that had been dispersed in underground bunkers during the day. First out were armored vehicles who’s job it was to set off any magnetic delay mines dropped on the Trail during the day. They drove quickly. The next Binh Tram would be a night’s drive away. Drivers only drove one section, back and forth, so were intimately aware of the conditions. Around three in the morning they would arrive, the trucks would be parked in hill side bunkers while the supplies would be dispersed again underground.

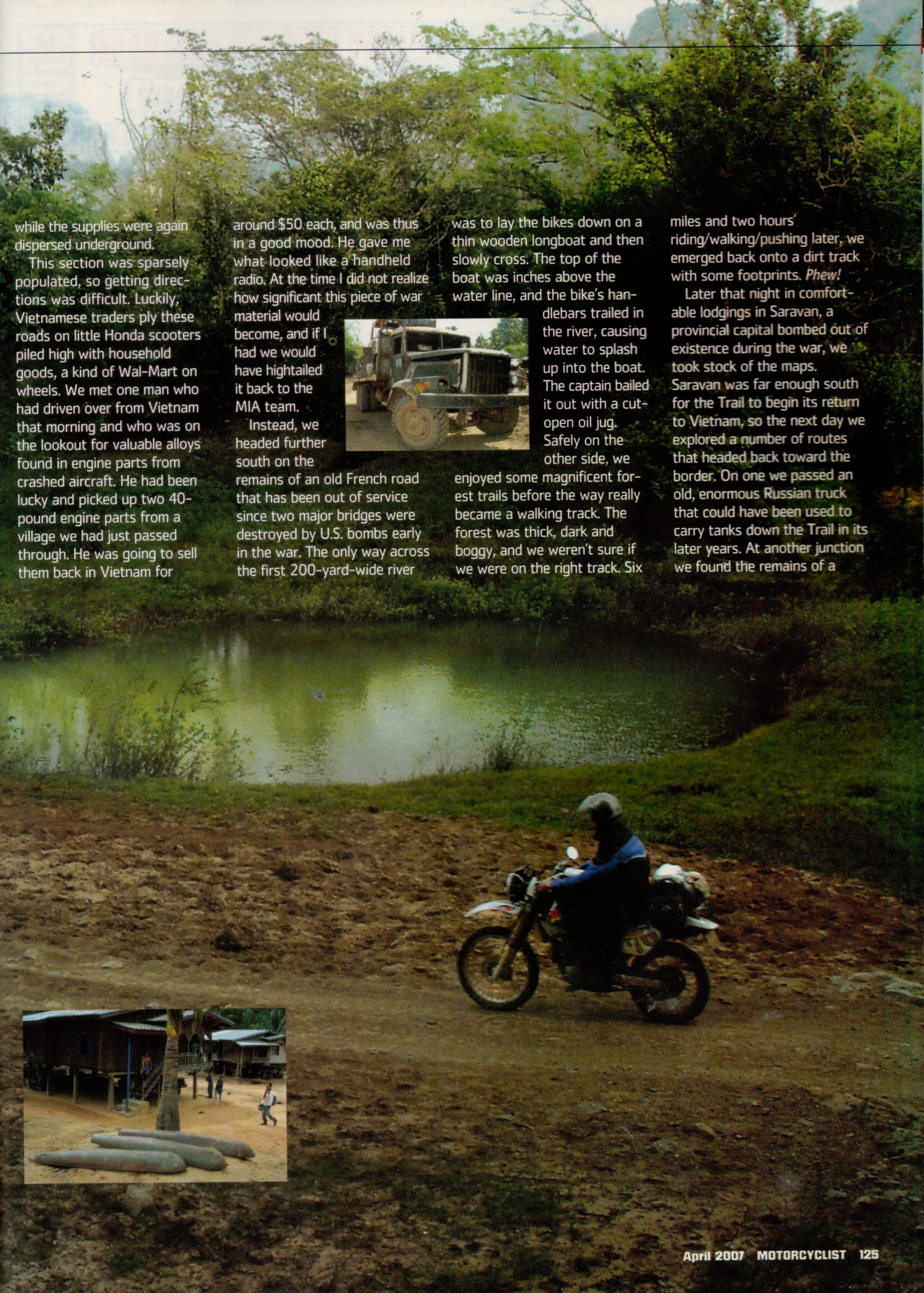

This section was sparsely populated so getting directions was difficult. Luckily, Vietnamese traders plied these roads on little Honda scooters piled high with house hold goods, a kind of Wall Mart on wheels. We met one man who had driven over from Vietnam that morning, and who was on the lookout for valuable alloys found in engine parts from crashed aircraft. He had been lucky, and had picked up two 20 kilo engine parts from a village we had just passed through. We was going to sell them back in Vietnam for around US$50 each and was in a good mood. He gave me what looked like a hand held radio. At the time I did not realize how significant this piece of war material would become and if I had we would have high tailed it back to the MIA team.

Continuing South

Instead we headed further south on the remains of an old French road that has been out of action ever since two major bridges were destroyed by US bombs early on in the war. The only way across the first bridge-less river was to lay the bikes down on a thin wooden long boat and then slowly cross the 200-meter-wide river. The top of the boat was only inches above the water line and the bike’s handle bars trailed in the river, causing a lot of water to splash up into the boat. The driver bailed it out with a cut-open oil jug. Once safely on the other side we enjoyed some magnificent forest trails before the way really became a walking track. The forest was thick, dark and boggy and we were not sure if we were on the right track. Ten kilometers later and two hours worth of jungle driving/walking/pushing we emerged back onto just a dirt track with some foot prints. Phew!

Later that night in comfortable lodgings in Saravan, a provincial capital bombed out of existence during the war, we took stock of the maps. Saravan was far enough south for the Trail to begin its return to Vietnam so we explored a number of routes that headed back towards the border. On one we passed an enormous old Russian truck that could have been used to carry tanks down the Trail in its later years. At another junction we found the remains of a SAAM missile. While these missiles did score some hits during the war, their importance was more strategic than tactical as they forced the US planes to fly higher and therefore drop their bombs more inaccurately.

During the later parts of the war the Americans launched a number of seasonal campaigns, all called Operation Hunt. The stated objectives were to target trucks, the Trail, the bases and AAA/SAAM sites but the real mission was to delay an invasion of South Vietnam and to make the Vietnamese pay in blood for their effort. During such campaigns there could easily be up to 300 sorties every day. A particularly lethal US aircraft was the propeller driven C-130 gun ship, called the “Spectre”. Kitted out with night vision, heat and magnetic detectors, the latest in electronic gizmos and four high powered machine guns, these planes could circle their targets firing 5,000 rounds a minute.

Navigating the Trail

We continued southwards and spent a day pushing tracks towards Ta Oi, another important junction during the war, which unfortunately always petered out into walking paths. The jungle, it seemed, had retaken this part of the Trail. There were hundreds of oil drums scattered along the sides of the Trail, and houses were even perched up on them. Many were peppered with bullet holes. I looked at a Vietnamese map of the Trail and found that there were three major depots hidden there during the war. The Vietnamese called these depots “binh trams’ and there were about 30 stretched out evenly along the Trail. Each was a semi-autonomous unit, boasting hospitals, truck storage areas, repair shops, fuel depots and sleeping quarters. Each night the heavily camouflaged trucks would be loaded up with supplies that had been dispersed in underground bunkers during the day. First out were armoured vehicles whose job it was to set off any magnetic delay mines dropped on the Trail during the day. They drove quickly. The next binh tram would be a night’s drive away. Drivers only drove one section, back and forth, so were intimately aware of the conditions. Around three in the morning they would arrive, the trucks would be parked in hillside bunkers while the supplies would again be dispersed underground.

This section was sparsely populated so getting directions was difficult. Luckily, Vietnamese traders plied these roads on little Honda scooters piled high with household goods, a kind of Woolworths on wheels. We’d frequently be struggling along a rocky track our 250cc dirt bikes when one of these overloaded scooters would zoom past. We met one man who had driven over from Vietnam that morning, and who was on the lookout for valuable alloys found in engine parts from crashed aircraft. He had been lucky, and had picked up two 20-kilo engine parts from a village we had just passed through. He was going to sell them back in Vietnam for about A$60 each and was in a good mood. He gave me what looked like a handheld radio. At the time I did not realise how significant this piece of war material would become, and if I had, we would have high-tailed it back to the MIA team.

Instead we headed further south on the remains of an old French road that has been out of action ever since two major bridges were destroyed by US bombs early on in the war. The only way across the first bridge-less river was to lie the bikes down on a thin wooden long boat and then slowly cross the 200-metre-wide river. The top of the boat was only inches above the water line and the bike’s handlebars trailed in the river, causing a lot of water to splash up into the boat. The boatman bailed it out with a cut-open oil jug. Once safely on the other side, we enjoyed some magnificent forest trails before the way really became a walking track. The forest was thick, dark and boggy and we were not sure if we were on the right track. Ten kilometres later and two hours worth of jungle driving, walking and pushing, we emerged back onto just a dirt track with some foot prints. Phew!

Later that night in comfortable lodgings in Saravan, a provincial capital bombed out of existence during the war, we took stock of the maps. Saravan was far enough south for the Trail to begin its return to Vietnam so we explored a number of routes that headed back towards the border. On one we passed an enormous old Russian truck that could have been used to carry tanks down the Trail in its later years. At another junction we found the remains of a SAM missile. While these missiles did score some hits during the war, their importance was more strategic than tactical as they forced the US planes to fly higher and therefore drop their bombs more inaccurately.

During the later parts of the war the Americans launched a number of seasonal campaigns, all called Operation Hunt. The stated objectives were to target trucks, the Trail, the bases and AAA/SAAM sites but the real mission was to delay an invasion of South Vietnam and to make the Vietnamese pay in blood for their effort. During such campaigns there could easily be up to 300 sorties every day. A particularly lethal US aircraft was the propeller driven C-130 gun ship, called the “Spectre”. Kitted out with night vision, heat and magnetic detectors, the latest in electronic gizmos and four high powered machine guns, these planes could circle their targets firing 5,000 rounds a minute.

Leghorn Listening Base

As we entered the very south of Laos, the Bolevan Plateau began to take shape on the horizon. Early on in the war US Special Forces had trained local hill tribe men from this plateau to become clandestine road watching teams. Special Forces teams, dressed as civilians instructed these men to recognize the vehicles used by Vietnam. They would be inserted at various junctions along the Trail and report back by radio. Another particularly hazardous mission carried out by Special Forces teams was the installation and running of the secret Leghorn listening base. Perched on top of a cliff lined mountain and accessible only by helicopter, this base was used to direct bombing runs and to support Special Forces operations into areas around this southern end of the Trail.

Ironically, a new highway recently built by the Vietnamese passes within eyeshot of the remains of this base. This same road marks the end of the Trail as it re-enters Vietnam near the Tri border with Laos and Cambodia. We learnt from road workers that a year ago local people found a way past the mines and up to the Leghorn base, where they promptly removed all the metal by cutting it up with oxy torches. The border was not open to foreigners and we could not re-enter Vietnam. However the route, like the road through the Mu Gia pass, will eventually become a major cross-border artery connecting all the countries in Indochina.

Low Tech War Effort

The ride took us twelve days by motorbike, whereas during the war soldiers could march it in six weeks. While at the height of the war the US needed some 14,000 tones of supplies every day to keep its forces in the field, the Vietnamese required only 20-60 tones. Remembering that a single truck could carry from 5-9 tones and that an estimated 3,000 trucks worked the Trail at any one time, not to mention the porters, it is little wonder that enough supplies got through every day despite the bombing effort.

A post war US study found that the A-1 propeller driven bomber destroyed an average of 12.8 trucks per 100 sorties for a cost of US$55,000 per target. Compare this to the jets which averaged only 1.5 trucks per 100 sorties for a cost of US$700,000 per target! Every B-52 attack cost around US$90,000, with half that sum being the cost of the bombs, and that’s in 1970 dollars! Little wonder that a protracted conflict turned into Vietnam’s strategic advantage. It simply cost too much.

By waging a low tech war effort which saw the widespread dispersal of trucks and supplies, the Vietnamese denied the US with lucrative targets. A road is a difficult target, especially when tens of thousands of road repair crews were willing to brave mines, cluster bombs and delayed fuse bombs to keep it open. Trucks were even harder to hit, especially when they were heavily camouflaged, driven at night by experienced crews, on trails that had triple layered canopies of cover. So despite the bombs, jets and napalm, the Trail was kept open and the war in the south continued to America’s disadvantage. However, life on the ground was a terrible ordeal, and an estimated 30,000 people died keeping the Trail open. From a captured Vietnamese soldier the following quote was taken from his diary.

“Southern Laos. This place is miserable. The green jungle is full of birds twittering. Flies sting and sting, and the holes don’t stop bleeding.”

Upon return to Hanoi I learnt that the radio was an emergency recon beacon carried by every US pilot to aid search and rescue. According to the war records, a helicopter carrying a Special Forces team was shot down in the same valley we found the radio. The MIA office in Hanoi has been contacted.

More Articles

ADV Rider Magazine

by Sean Goldhawk

Rider Magazine

by Perri Capell

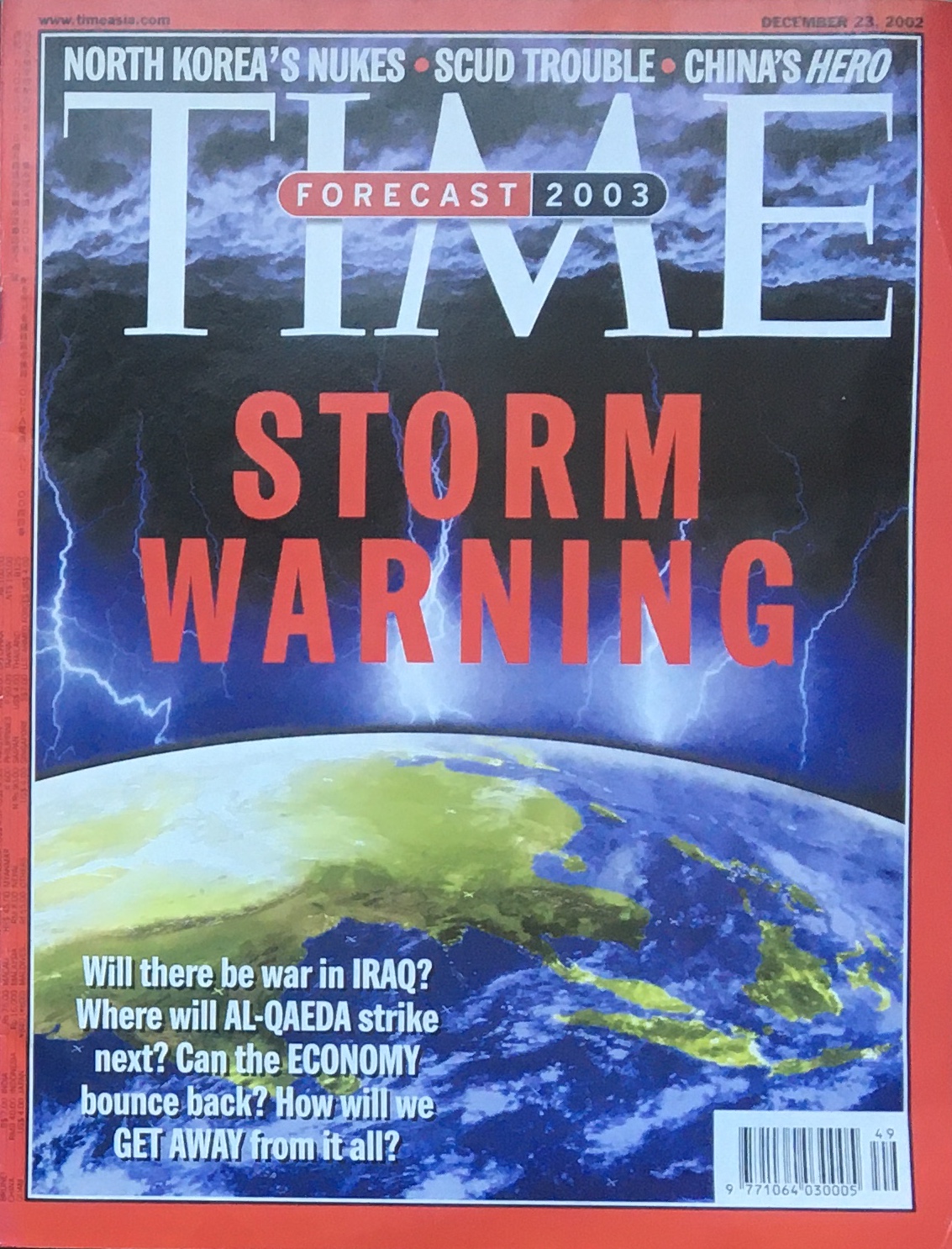

TIME Magazine Asia

by Kay Johnson