Two Wheels

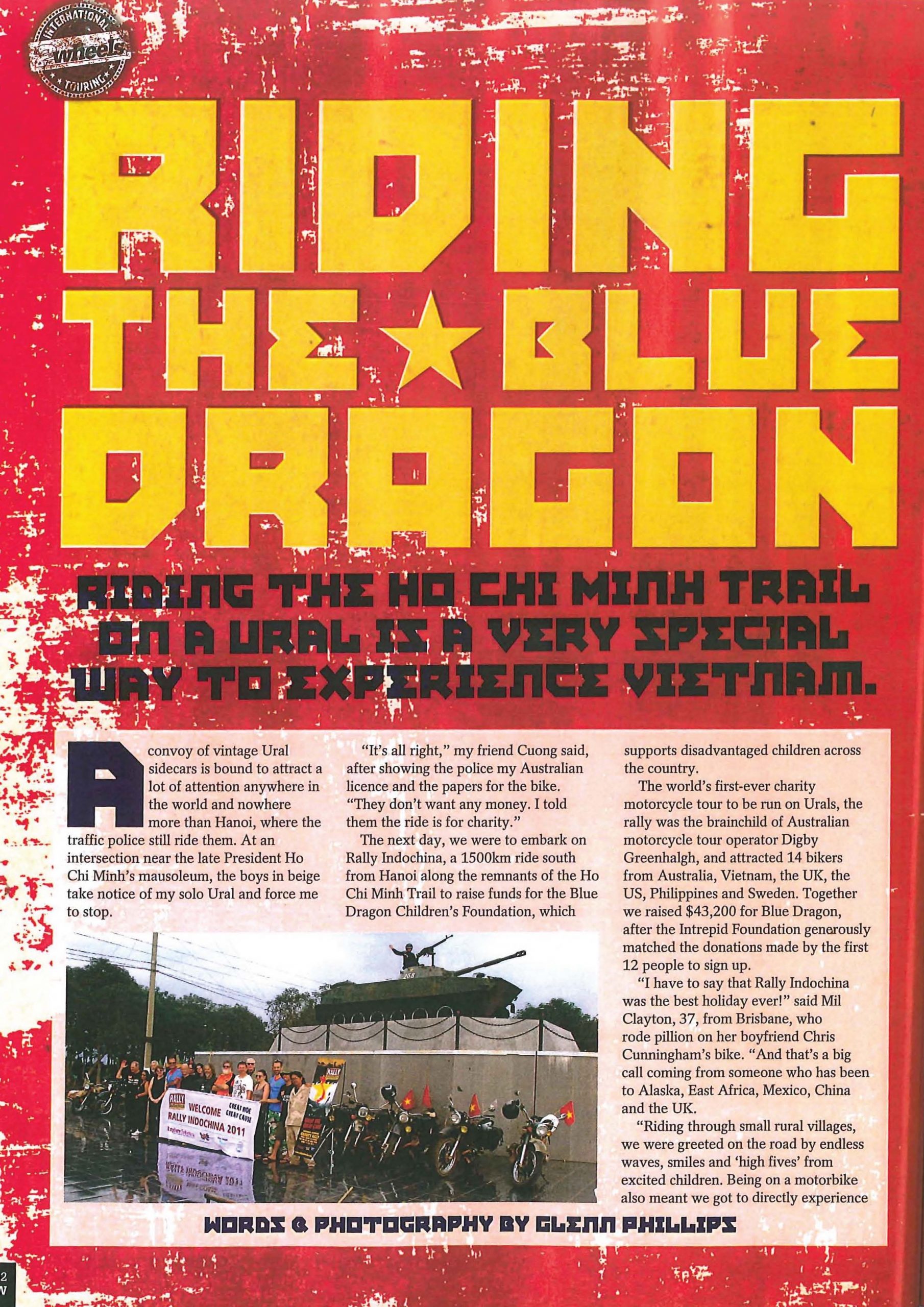

Riding the Blue Dragon

by Glenn Phillips

Rally Indochina

Riding the Ho Chi Minh Trail on a Ural is a very special way to experience Vietnam.

A convoy of vintage Ural sidecars is bound to attract a lot of attention anywhere in the world, and nowhere more than Hanoi, where the traffic police still ride them. At an intersection near the late President Ho Chi Minh’s mausoleum, the boys in beige take notice of my solo Ural and force me to stop.

“It’s all right,” my friend Cuong said, after showing the police my Australian licence and the papers for the bike. “They don’t want any money. I told them the ride is for charity.”

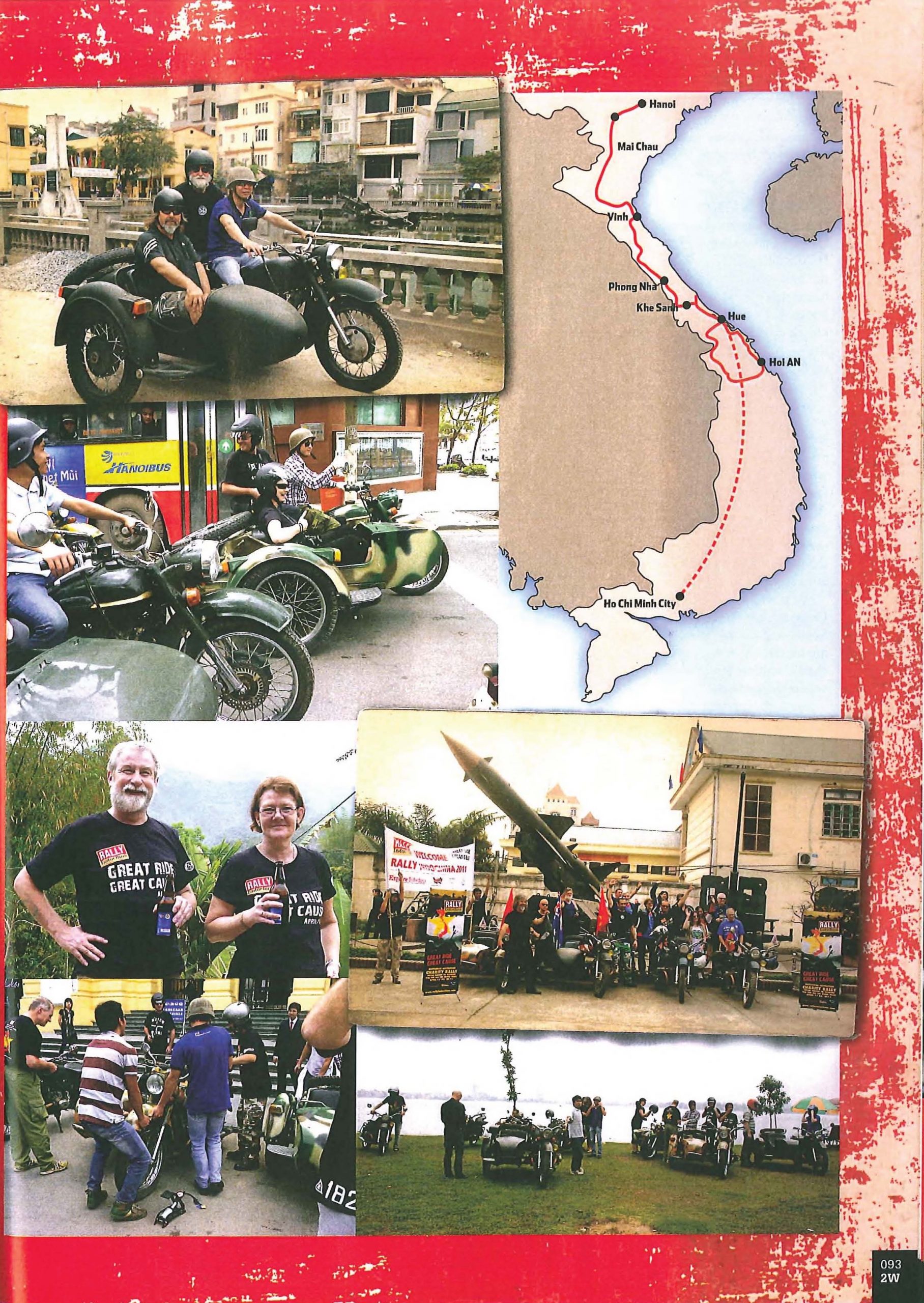

The next day, we were to embark on Rally Indochina, a 1500km ride south from Hanoi along the remnants of the Ho Chi Minh Trail to raise funds for the Blue Dragon Children’s Foundation, which supports disadvantaged children across the country.

The world’s first-ever charity motorcycle tour to be run on Urals, the rally was the brainchild of Australian motorcycle tour operator Digby Greenhalgh, and attracted 14 bikers from Australia, Vietnam, the UK, the US, Philippines and Sweden. Together we raised $43,200 for Blue Dragon, after the Intrepid Foundation generously matched the donations made by the first 12 people to sign up.

Best Holiday Ever

“I have to say that Rally Indochina was the best holiday ever!” said Mil Clayton, 37, from Brisbane, who rode pillion on her boyfriend Chris Cunningham’s bike. “And that’s a big call coming from someone who has been to Alaska, East Africa, Mexico, China and the UK.

“Riding through small rural villages, we were greeted on the road by endless waves, smiles and ‘high fives’ from excited children. Being on a motorbike also meant we got to directly experience the changes in the weather, the smells from shops on the side of the road, and at times ride side-by-side with the locals on scooters that were often laden with livestock.”

Great Ride

Our ride began on the outskirts of Hanoi, at a museum dedicated to the Ho Chi Minh Trail. During the war, the trail was an extensive network of tracks and roads on both sides of the border between Vietnam and Laos. We kick-started our Soviet-era bikes in the shadow of trucks and artillery pieces that had served on the trail and headed west towards the Lao border.

There are constant reminders of the war in Vinh, a coastal city that is widely seen as the ugliest town in Vietnam. An essential port and rail hub during the war, Vinh was the source of much of the traffic down the Ho Chi Minh Trail. American bombs almost completely destroyed the city and, if that wasn’t enough, it was rebuilt after the war with the latest in Soviet town planning: row after row of concrete flats.

We pose for photographs beside our Urals at Vinh’s military museum, where Soviet surface-to-air missiles and MiGs are on display, while pretty young female soldiers tend the museum’s vegetable gardens.

South of Vinh, we ride into the Dong Loc intersection where US bombs killed 10 young women on the same day in July, 1968. An enormous statue of three soldiers rises before us and we pass by a solemn cemetery where the 10 female volunteers were buried. Local visitors pay their respects at the graves with offerings of incense, white lilies, combs and mirrors, as well as paper dresses, handbags and shoes.

Vietnam's Best-Kept Motorbiking Secret

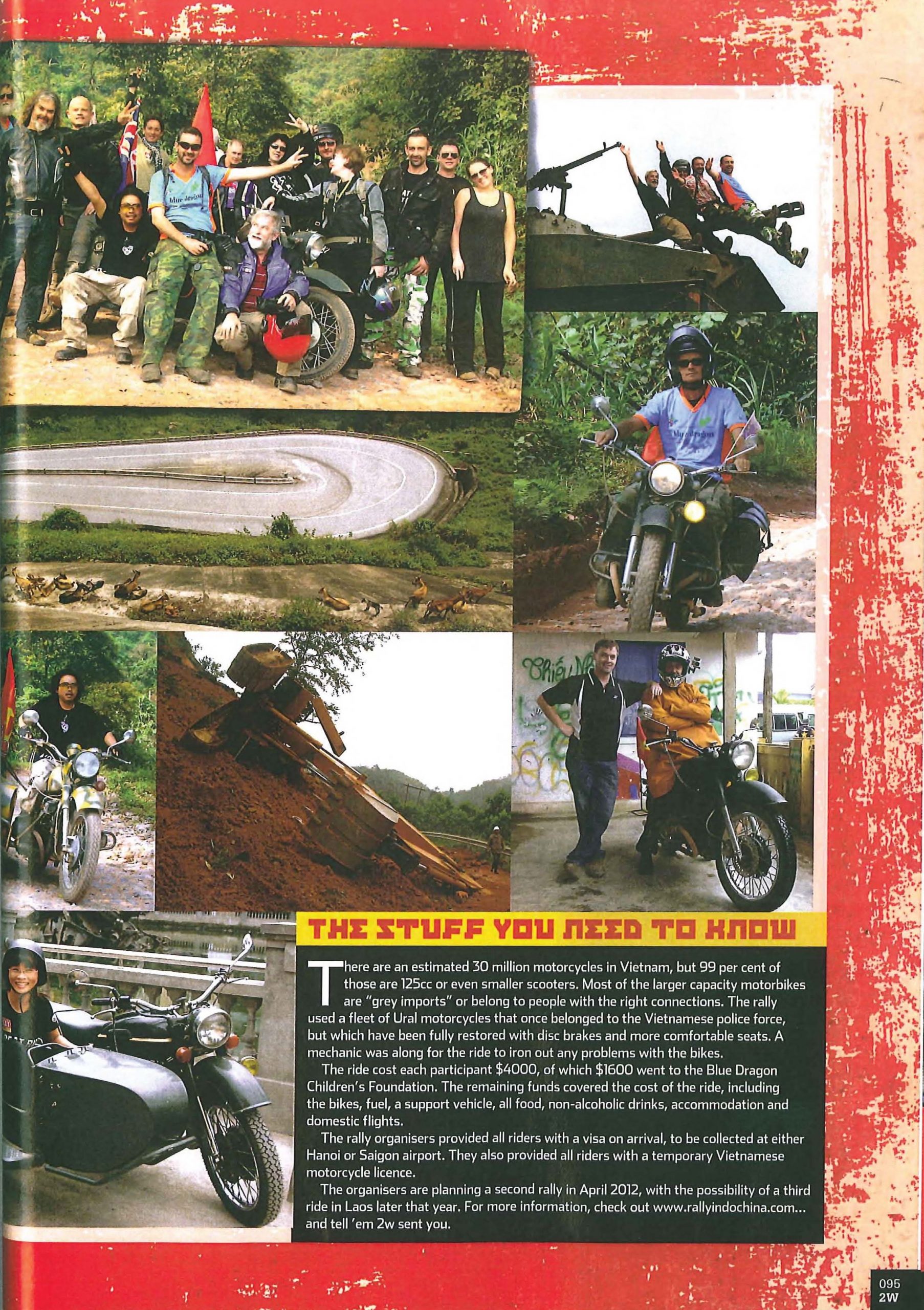

One of best-kept motorbiking secrets in Vietnam is the 240km stretch north of Khe Sanh, where the Ho Chi Minh Highway cuts through the Phong Nha National Park and past a few isolated hill-tribe villages. The only way onto this road is with special permission from the park rangers, police and border guards and, luckily for us, Cuong has spent years courting them all.

The forestry rangers open the boom gates and let us onto one of the best motorcycling roads in south-east Asia, seemingly designed with our Urals in mind. There are bends inside the bends, if only someone would sweep the gravel off the corners. We cross the 17th Parallel and climb to over 1100m on a mountain pass above Khe Sanh, rolling down to the former US Marine Corp base just before sunset.

As we ride to the former US Special Forces camp at Lang Vay, where all that remains is a solitary tank on a hilltop, one of our group quips: “Let me guess, another photo op!”

A yoga instructor from Perth, Bill Johnson, startles a group of Vietnamese veterans from the war by standing on his head underneath the Russian tank that the North Vietnamese had used to overrun the camp in 1968.

The Stuff You Need to Know

There are an estimated 30 million motorcycles in Vietnam, but 99 per cent of those are 125cc or even smaller scooters. Most of the larger capacity motorbikes are “grey imports” or belong to the people with the right connections. The rally used a fleet of Ural motorcycles that once belonged to the Vietnamese police force, but which had been fully restored with disc brakes and more comfortable seats. A mechanic was along for the ride to iron out any problems with the bikes.

The ride cost each participant $4000, of which $1600 went to the Blue Dragon Children’s Foundation. The remaining funds covered the cost of the ride, including the bikes, fuel, a support vehicle, all food, non-alcoholic drinks, accommodation and domestic flights.

The rally organisers provided all riders with a visa on arrival, to be collected at either Hanoi or Saigon airport. They also provided all riders with a temporary Vietnamese motorcycle license.

The organisers are planning a second rally in April 2012, with the possibility of a third ride in Laos that year. For more information, check out www.rallyindochina.com and tell ’em 2w sent you.

Very Superstitious

Years of touring on a motorbike can make you as superstitious as an old sailor. Don’t mention the good weather or it will rain; don’t say how well the bikes are running or you’ll get a flat tyre; and never, ever comment on how you’re making good time.

After visiting the Blue Dragon centre in Hue, Michael Brosowski joins us the next day for the long ride through the Truong Son mountains in a restored US Army jeep. It’s not long before we encounter a huge old bus bogged down in some roadworks and jammed up hard against the guardrail. We’re stuck for three quarters of an hour until someone finds some mud chains and fits them to the bus.

On the very next bend, a local biker but not without breaking some ribs. drops his scooter in the roadworks, leaves it where it falls and hurriedly flees the scene. Puzzled, I look up, where the ground is beginning to give way under an excavator. It flips over, puncturing the tarmac as the boom hits the deck, but not before the driver leaps to safety.

Bad things always happen in threes, and before we reached the A Shau valley, our friend Vinh (no relation to the ugly city) had to eject himself from his Ural sidecar. Coming around a bend with the car off the ground, he spots some traffic cops and puts the third wheel back on the ground, sending the bike careering towards the cops. Jumping off the outfit and over a barbed wire fence, Vinh escapes without a fine but not without breaking some ribs.

Blowing a Piston

Perhaps Michael wasn’t to blame for our bad luck after all. We part ways with him in Hoi An and, on the final day of riding, Chris and Mil’s Ural blows a piston after crossing over the Hai Van pass. It was time for the rally’s support crew to get their hands dirty.

“After seeing Cuong and Phu pull the bike apart with little more than a hammer, a stone, a socket wrench and a rubber band, we really wanted to bring the old Ural home,” Mil said. “Chris and I enjoyed every single day on the bike. If Cuong wanted to sell any off, we’d seriously buy one.”

All In a Great Cause

Despite heavy rain, we jump on our bikes in the historic city of Hue and head out to the beach. The Blue Dragon Children’s Foundation, which was established in 2003 by Australian teacher Michael Brosowski, has a centre in a fishing village at the mouth of the Tam Giang lagoon where they work to prevent local children from being trafficked to illegal sweatshops in Ho Chi Minh City.

Falling fish stocks, rising fuel prices and typhoons make life difficult for the villagers, and many fishing families cannot afford to put their children through school. They are easy prey for traffickers who come to the village promising to take the children to Ho Chi Minh City and educate them but, instead, put them to work in slave-like conditions. Blue Dragon has rescued 92 local children from sweatshops so far and works with the local community to warn the families and prevent children from being trafficked in future.

After a picnic lunch at the centre with local children, some of whom had been rescued from the traffickers, we visited the beach where Blue Dragon and Red Cross Vietnam are building homes for impoverished local families. At the lagoon, the United Nations is helping fishermen to learn how to farm fish in the estuary.

“It was wonderful to officially hand over the ‘big cheque’ to Blue Dragon and know that the money would be gratefully used by the foundation,” Mil Clayton said. “A truly great cause!”

More Articles

ADV Rider Magazine

by Sean Goldhawk

Rider Magazine

by Perri Capell

TIME Magazine Asia

by Kay Johnson