Travel + Leisure

Riding High

by Newley Purnell

Karst Outcrops and Dusty Villages

“If you hit something going just 35 kilometers an hour, you’re in with half a chance. We won’t have to wash you off the road.” That’s Digby Greenhalgh, my motorbike guide, giving me some sensible pre-ride advice. We’re getting our gear together before setting off on a tour of Vietnam’s rugged northeast. I try on my padded blue jacket, gray helmet and reinforced gloves. Everything fits. I’m ready. Or at least I think I am.

Greenhalgh is a 38-year-old Australian who’s lived in Hanoi for the last 12 years—at least three of which, he reckons, he’s spent on the road. He runs a Hanoi-based tour company that guides visitors through rarely visited parts of north Vietnam on enigmatic Soviet-era Minsk motorbikes.

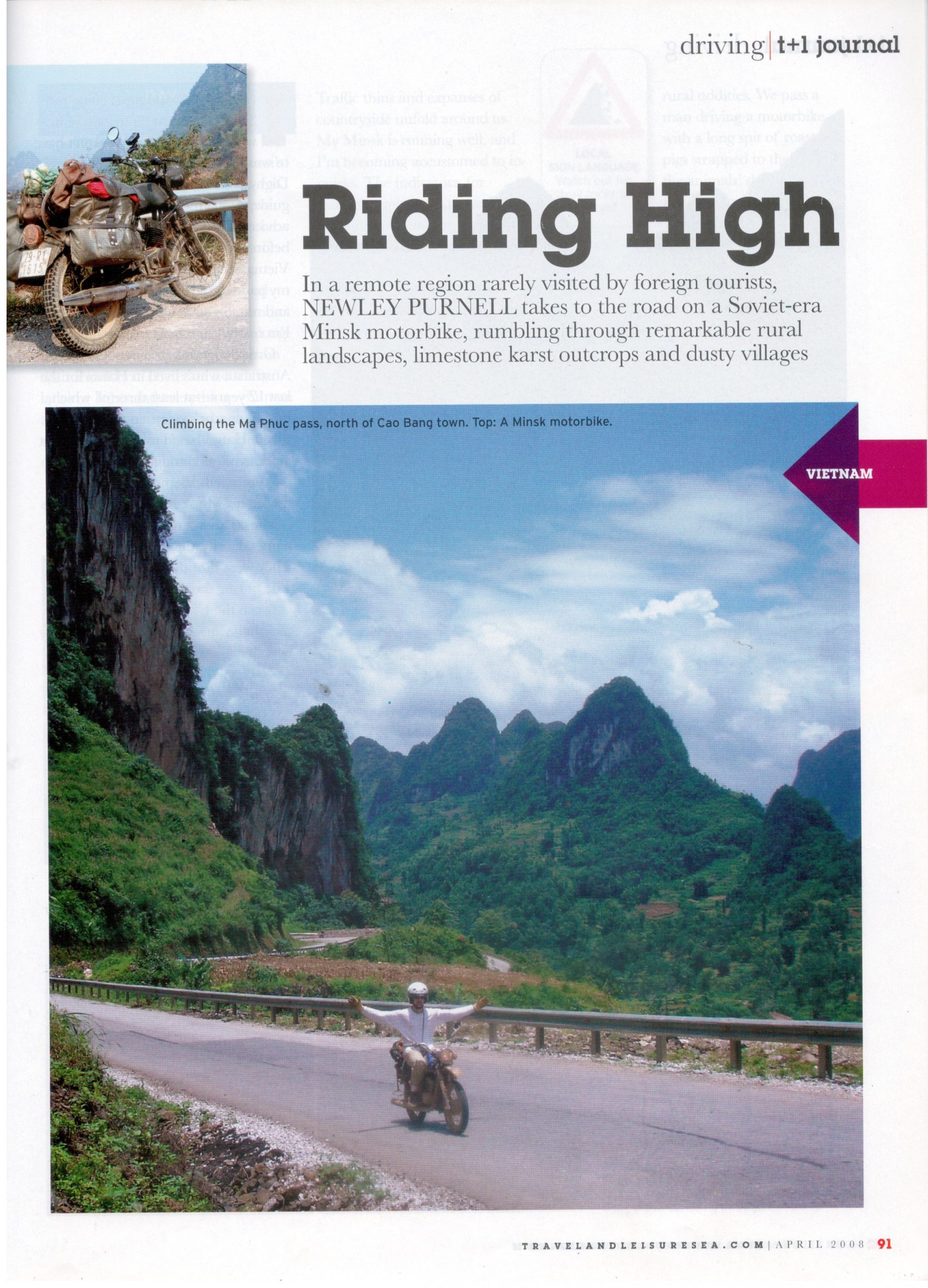

Minsks are manufactured in their namesake city, the capital of Belarus. They were introduced to Southeast Asia during the days of collaboration between the USSR and Vietnam, and their bulky design has remained largely unchanged ever since. “The Minsk is all you need here,” Greenhalgh says. “Conditions dictate that you go slow.” Locals call these utilitarian bikes “buffalo” for their bovine attributes: obedient (mostly), occasionally ornery and cheap to maintain. While urbanites in other parts of the country opt for shiny new Hondas and Yamahas, the two-stroke Minsk is the economical workhorse for Vietnam’s rural people.

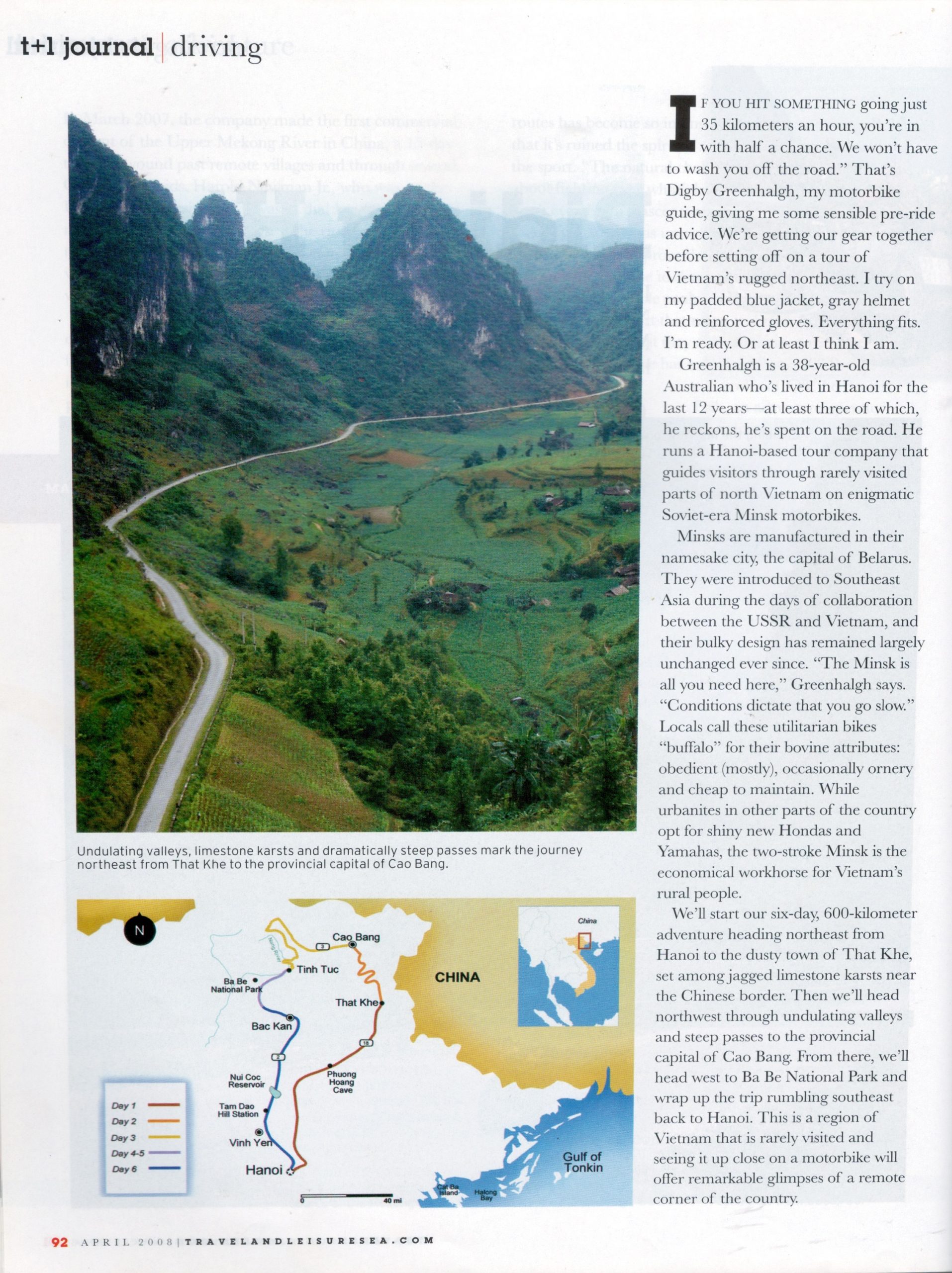

We’ll start our six-day, 600-kilometer adventure heading northeast from Hanoi to the dusty town of That Khe, set among jagged limestone karsts near the Chinese border. Then we’ll head northwest through undulating valleys and steep passes to the provincial capital of Cao Bang. From there, we’ll head west to Ba Be National Park and wrap up the trip rumbling southeast back to Hanoi. This is a region of Vietnam that is rarely visited and seeing it up close on a motorbike will offer remarkable glimpses of a remote corner of the country.

Day 1: Hanoi to That Khe (180km)

Greenhalgh and I set off into Hanoi’s notoriously chaotic traffic at 7:30 A.M. Chilly winter air rushes through my helmet, but soon I’m warmed by the strengthening sun. Even at this early hour, the city is choked with cars, motorbikes, trucks, pedestrians and food vendors. Horns bleat incessantly and women in conical hats plod along the streets carrying wicker baskets on their shoulders. There are no traffic lanes or lights and everything—human and machine—merges, swerves, stops, starts, accelerates. There are no collisions, but innumerable close calls. An hour outside of Hanoi, the expressway turns into a two-lane road.

Traffic thins and expanses of countryside unfold around us. My Minsk is running well, and I’m becoming accustomed to its quirks. The indicators, for example, only seem to work in fits and starts, and my speedometer appears to have died. We stop at a roadside café for viscous black coffee and slices of pear. We’re entering a region of the heartland, Greenhalgh tells me, where Ho Chi Minh first assembled his army, waging war first on the French and then on the Americans. Later in the day, limestone karsts begin to pop up all around us—these dramatic brown and black jagged hills form a sort of inland version of Halong Bay. We’re far from Hanoi now, and I begin to catch glimpses of rural oddities. We pass a man driving a motorbike with a long spit of roasted pigs strapped to the back, the animals’ skin crispy and their eye sockets gaping. Then we see a squirming calf lashed to the back of a motorbike trundling down the highway.

At the end of the first day’s ride my body aches. The last 7 kilometers have been particularly rough, the rutted dirt track rattling my back and shoulders. My lips are painfully dry, but I’m still exhilarated by the ride. We arrive at a crumbling hotel in the old French fortified town of That Khe—a dull place of anonymous and worn concrete buildings. The sun is setting and everything glows red. We eat fried spring rolls, green beans and boiled potatoes for dinner, and a group of young Vietnamese men playing pool in a tiny hall across the street from our hotel invite us to join them. They toast us with numerous glasses of vodka and invite us to sample a handmade bamboo water pipe.

Day 2: That Khe to Cao Bang (70km)

The town springs to life below our hotel window at 5 A.M. People yell to one another and trucks rumble by. We get up, thickheaded from the last nights vodka splurge and frigid from the lack of heat in our room, so we cross the street in search of breakfast. An old woman, her face deeply wrinkled, sells us rice pancakes with minced meat. Thick steam rises from her grill in the cool of the morning. Soon we are back on the road.

At noon, we arrive at a truck stop overlooking a rich, verdant valley. Three boys approach us on bicycles to inspect our Minsks and-eye us curiously. We’re traveling on Highway 4, which runs along the Chinese border, just to our north. Greenhalgh asks them in rudimentary Mandarin if they speak Chinese. “No, no, no,” the tallest boy responds in Vietnamese. “We don’t speak Chinese,” he says, smiling and pointing over his shoulder. “But they do over there in China.”

Further on, we see a woman tending a fire, burning what appear to be medium-sized animals. Could they be goats? We stop to look. They’re dogs, and she’s roasting them to remove their fur—the meat is considered a delicacy throughout Vietnam. Just as I’m examining the fire and its contents, a man approaches me from behind and lowers another canine into the flames, its stiff legs askew. Later that day, we arrive at a cavernous, government-run hotel in the provincial capital of Cao Bang, a nondescript city on the banks of the Bang Giang River. It’s a bit warmer here, although we still need heavy the wide city streets before turning in early.

Day 3: Cao Bang to Tinh Tuc (105km)

The day’s the ride takes us through terrain resembling a mountainous lunarscape, with vehicle-size rocks nudging out of the earth like hulking gravestones. When we pass through villages, children smile and wave, while people tending the fields stop working and stare as we ride by. That night we stay in the dilapidated mining town of Tinh Tuc. The place is overwhelmingly gray, and made even more somber when a mist throws a shroud over the town. The building next door to our drafty hotel is a mixed-business treat of dog-meat restaurant, karaoke bar and brothel.

Day 4: Tinh Tuc to Ba Be National Park (45km)

“We’re going to do some serious off roading today,” Greenhalgh informs me in the morning. I am slightly unnerved, being more of a weekend joyrider than a hardcore biker. Greenhalgh leads the way, and soon we turn off’ a dusty dirt track and head along steep hillsides. I dodge large tree stumps and hill-sized rocks, worried that my tires will burst at any moment. Sections of the terrain are so steep we barely creep along in first gear, our engines whining. My Minsk isn’t idling fast enough and occasionally clatters to a stop.

Some people claim that time appears to slow during an accident, but in my case, time seemed to accelerate wildly. I’m about to descend a steep embankment, and as I’m carefully coasting towards the precipice, my Minsk lurches to an unexpected stop (I’ve accidentally jammed the brakes) and I’m bucked headfirst off the bike. As my torso hits the ground, I begin an ignominious downhill slide, but I’m stopped short of the edge by a heavy weight. I look back and stare upwards. The bike has tipped over and landed on me, crushing my left ankle. My faithful Minsk has saved me from a plummet of shame—and harm. Only Greenhalgh, who had stopped up ahead, has witnessed my spill. He lifts the motorbike off me, and I brush myself off. I’m unhurt and we drive away. Soon, thankfully, we’re on a sealed road. As darkness approaches, we stop at a hotel in the densely forested Ba Be National Park.

Day 5: Boat Ride on Ba Be Lake (8km)

At breakfast, we eat noodles at a small restaurant on the Ba Be Lake. It’s warmer now, and we work our way down to a river that feeds the lake, where Greenhalgh’s friend Dang has readied a small boat for us. We gingerly ride our bikes aboard and shove off. Soon, a mountain appears before us, and the river leads into a cave that cuts through its side. This is Phuong Cave, a 200-meter-long passageway. Dang stops the boat once we’ve entered. The fetid smell of guano is overpowering the cave is home to legions of bats. “Someone went in with a big light one time,” Dang says, “to see how many of them there are. There were too many to count.” We take the boat back to the lake and spend the night at Dang’s simple, two-story house, where he lives with his wife and five sons.

Day 6: Ba Be Lake to Hanoi (180km)

After fried eggs and baguettes for breakfast, we begin the long haul back to Hanoi on Highway 2. One, two, three and then four hours tick by. The longer we travel the highway, the more traffic appears on the road. We stop for a lunch of grilled shrimp, beef with green pepper and roasted corn. On the outskirts of Hanoi, on a long, flat stretch. of expressway, my Minsk begins to lose power. We stop and quickly identify the problem. It’s just a dirty spark plug—a problem easily fixed. We clean it, I kick-start my Minsk and we are once again headed for the capital. The Hanoi traffic is as tumultuous as ever, but it’s easier to navigate after so much time on rough roads. I say goodbye to Greenhalgh, relinquish my Minsk and return to my hotel. Vehicles weave along the street below my window. My body is stiff and I’m glad to get some rest. Still, I have to fight the urge to go back downstairs, wrest my Minsk back from Greenhalgh, and rejoin the flow of traffic once again.

Motorbike Tours

Explore Indochina organizes three- to nine- day motorbike trips through the north of Vietnam that can accommodate up to five riders per guide. The cost is US$150-US$270 per person daily, depending on the number of riders. This includes motorbike rental, fuel, lodging and meals. It’s also possible to ride as a pillion passenger.

More Articles

ADV Rider Magazine

by Sean Goldhawk

Rider Magazine

by Perri Capell

TIME Magazine Asia

by Kay Johnson