Time Out Magazine

In Minsk We Trust

by Mai Uyen Linh

A Pack of Minsk Madmen

It was enough to give a devoted Honda Benley rider a bad case of the shakes. Take a road trip with 32 Minsk riders? There’s a certain brand of insanity manifested by those who drive this archaic Russian motorbike that can be truly terrifying in group settings.

I remembered all too well how I had quaked with fear at the prospect of joining nearly 60 Minsk drivers to drink bia hoi, swap tales and rev their rusty engines at an impromptu get-together a month before. In the end I had skipped it, certain that my precious Benley would end up an unwilling sacrifice.

But reckless curiosity finally forced me to join the burly Minsk lovers on their first weekend rally to Mai Chau last month.

Afraid I would be run over if I joined the ferocious pack heading out of town that Saturday morning, I decided to set my own stately pace with another woman on a rented Benley after the Minsks left in a cloud of filth from Cafe 252.

Getting to Mai Chau

It did not matter that one lone Minsk driver managed to tag along with us—she was a woman, after all, and her new-model Minsk was so strange looking that it would take an expert to guess its make.

Our trio was one of the first to cruise into the White Thai village near Mai Chau at 2pm, except for two eager riders who had arrived the day before to pick out a plump pig for the afternoon barbecue and guzzle ruou can with the village chief.

Our pride at beating the pack was short-lived, however, when we realised that a group of hairy Russians had actually roared into town before us, having left at the ridiculous hour of 7am. The Russian riders were under the house in the shade, shirtless and covered in grease, alternately repairing their bikes and preparing the slaughtered pig for the spit.

Arrival of Digby and the Minsk Club

Within an hour or two, ragtag groups of riders had assembled at the house. The motley international blend included English teachers, researchers of obscure topics in Vietnamese history, environmentalists and the unemployed.

But without a doubt the leader of the pack was Digby Greenhalgh, a four-year Minsk veteran who brought up the rear with his amazing bundle of sprockets and rust that had once passed for a motorcycle.

Greenhalgh is the self-proclaimed expert on the fussy Russian machine. In fact, his main pastime is compiling information about how to get to the most beautiful places in northern Vietnam on—you guessed it—a Minsk.

Previously, he had told me with a smug grin, “I’ve spent 200 of the past 365 days on Vietnam’s back roads.” Strangely enough, however, his modern-day steed still didn’t even have a name. Next to my gleaming “Angelica”, his nameless Minsk did look tough, I had to admit, but somehow forlorn.

Ambivalence of the Minsk Rider

Perhaps that’s because there’s a certain amount of ambivalence that goes along with being a Minsk rider. Stretched out elastics hang off the backs and amateur paint jobs and exploded seats are almost de riguer.

Their general state of neglect probably has something to do with the fact that most Minsk drivers don’t plan on becoming one, and many never even drove a motorbike before coming to Vietnam.

Most Minsks come into their possession when a) a friend passed down their old machine when they left, or b) they bought their broken down bike for a couple hundred dollars or a few rounds of bia hoi.

But this is beside the point, really. The oft-neglected motorbike is really an excuse for like-minded souls to get together—an ad-hoc social club for those who don’t merit membership at the Hanoi Club, for instance.

There even seems to be a kind of uniform, for men and the few Minsk-riding women: army surplus pants, scuffed hiking boots, a handkerchief around the neck, and a farmer’s tan. It goes without saying that nobody wears a helmet.

Minsk Mogul Marcus Madeja

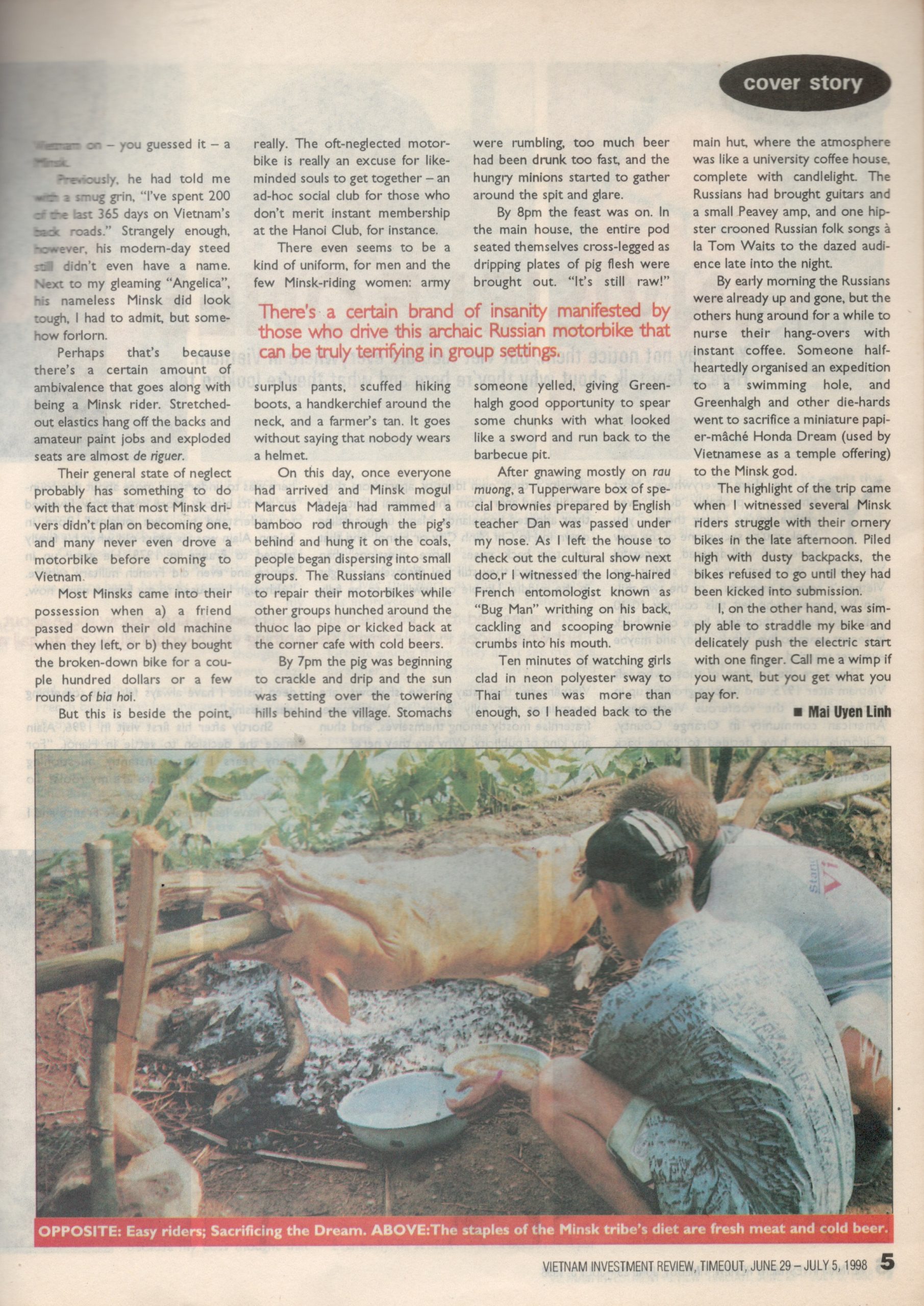

On this day, once everyone had arrived and Minsk mogul Marcus Madeja had rammed a bamboo rod through the pig’s behind and hung it on the coals, people began dispersing into small groups. The Russians continued to repair their motorbikes while other groups hunched around the thuoc lao pipe or kicked back at the corner cafe with cold beers.

By 7pm the pig was beginning to crackle and drip and the sun was setting over the towering hills behind the village. Stomachs were rumbling, too much beer had been drunk too fast, and the hungry minions started to gather around the spit and glare.

By 8pm the feast was on. In the main house, the entire pod seated themselves cross-legged as dripping plates of pig flesh were brought out. “It’s still raw!” someone yelled, giving Greenhalgh the opportunity to spear some chunks with what looked like a sword and run back to the barbecue pit.

After gnawing mostly on rau muong, a Tupperware box of special brownies prepared by English teacher Dan was passed under my nose. As I left the house to check out the cultural show next door, I witnessed the long-haired French entomologist known as “Bug Man” writhing his back, cackling and scooping brownie crumbs into his mouth.

Complete With Candlelight

Ten minutes of watching girls clad in neon polyester sway to Thai tunes was more than enough, so I headed back to the main hut, where the atmosphere was like a university coffee house, complete with candlelight. The Russians had brought guitars and a small Peavey amp, and one hipster crooned Russian folk songs à la Tom Waits to the dazed audience late into the night.

Going Home

By early morning the Russians were already up and gone, but the others hung around for a while to nurse their hangovers with instant coffee. Someone half-heartedly organised an expedition to a swimming hole, and Greenhalgh and other die-hards went to sacrifice a miniature papier-mâché Honda Dream (used by Vietnamese as a temple offering) to the Minsk God.

The highlight of the trip came when I witnessed several Minsk riders struggle with their ornery bikes in the late afternoon. Piled high with dusty backpacks, the bikes refused to go until they had been kicked into submission.

I, on the other hand, was simply able to straddle my bike and delicately push the electric start with one finger. Call me a wimp if you want, but you get what you pay for.

More Articles

ADV Rider Magazine

by Sean Goldhawk

Rider Magazine

by Perri Capell

TIME Magazine Asia

by Kay Johnson