Motorcycle Escape Magazine

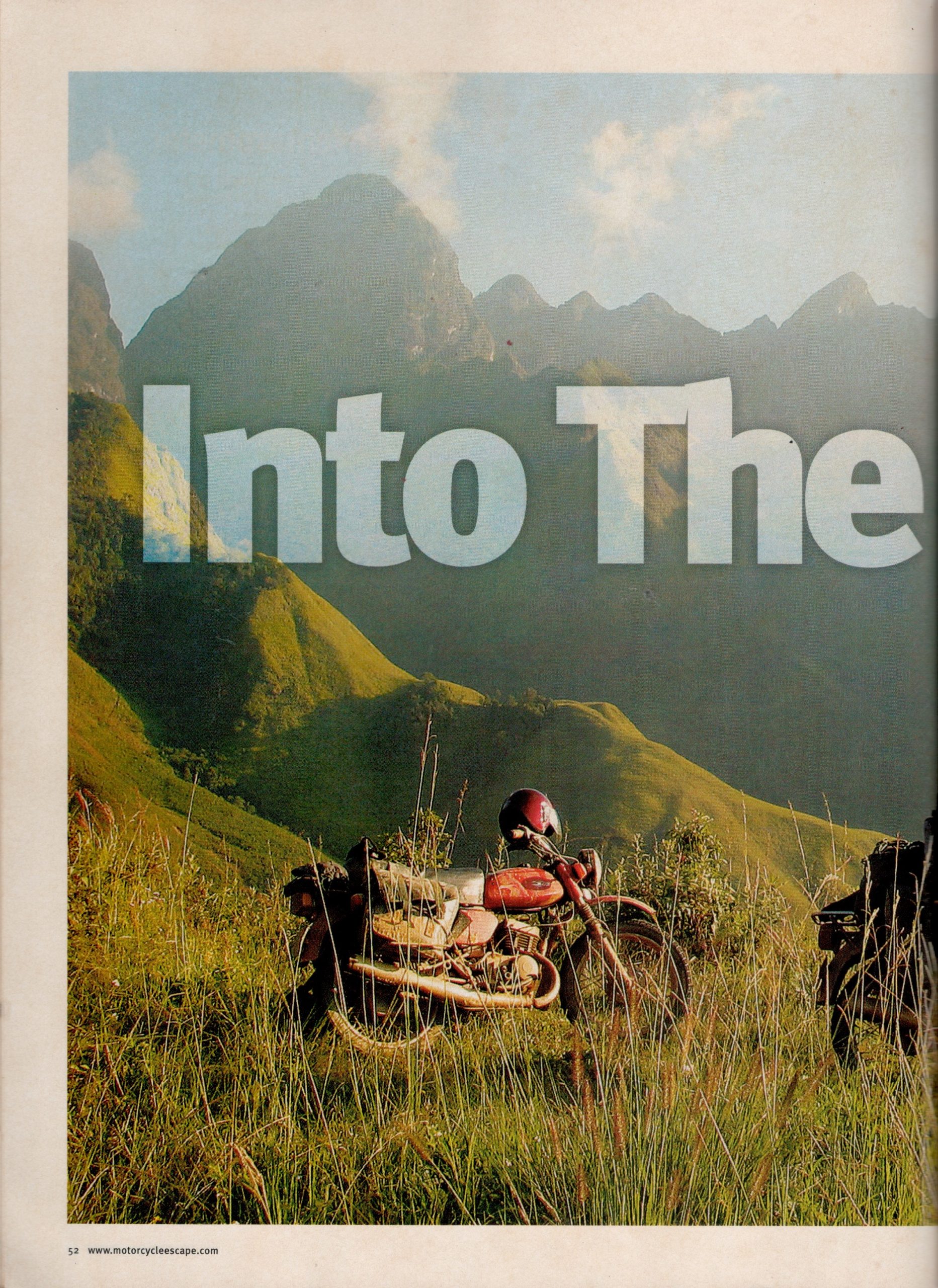

Into The Rice

by Andrew Cherney

Into The Rice

It’s 30 vertical feet from the edge of the road I’m standing on down to the ravine. Looking out past my toes, to where scrappy brush fights for a toehold in broken clumps of earth, I figure 30 feet isn’t that steep, at least as far as cliffs go. More importantly, though, I’m wondering if the guy I’d just seen tumble into it is still alive.

I’d just ridden down a narrow dirt track through a remote valley in North Vietnam’s mountainous Lao Cai province. Emerging from heavy brush, the road had quickly gone from grassy to muddy, with thick muck taking up most of the drivable area ahead. The only dry option is a narrow rope of dirt threading along the left side – the side that falls away into nothingness. Unbelievably, the rider in front of me had chosen this precarious line, and, having lost momentum – and his balance – teetered over into the nether regions. Then, nothing. Dumbstruck, I’d scrambled off my bike, scanning the pile of rocks below for signs of movement.

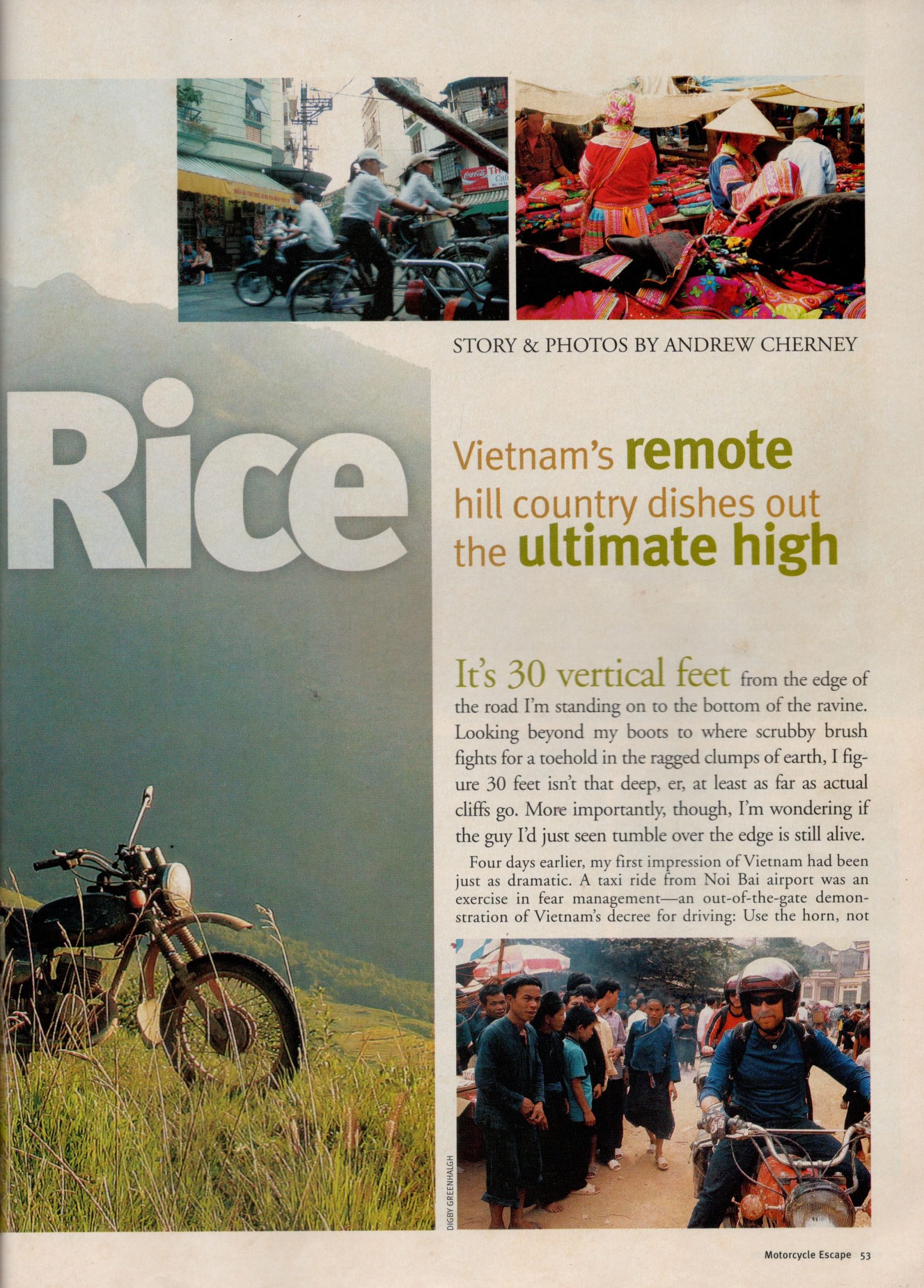

Four days earlier, my first impression of ‘Nam hadn’t been much better – the taxi ride from Noi Bai airport was an exercise in fear management. Although the journey only took 45 minutes, it offered a fascinating demonstration of the maxim behind Vietnam’s driving etiquette: use the horn, not the brake. My driver fearlessly swerved into oncoming lanes to pass slower vehicles and then, the Old Quarter district of Hanoi exploded around us like a low-tech Times Square.

The welcoming committee was a bizarre mix of decaying architecture and thousands of motorbikes zigzagging down narrow streets on collision courses. Hanoi’s old town was an odd mix of eastern spirituality and European colonial legacy. It was frenzied and utterly exhilarating.

The Plan

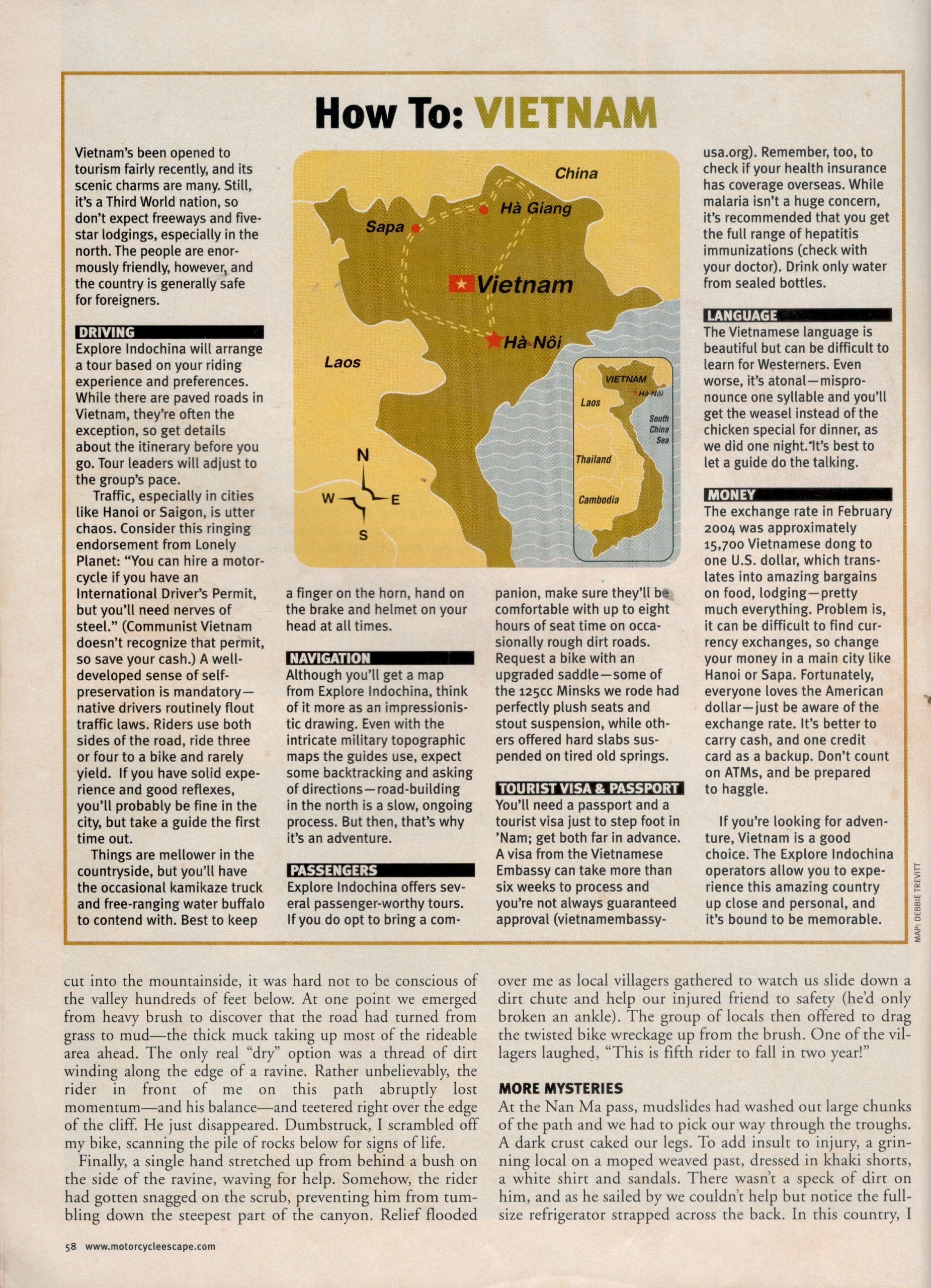

Shaped like an elongated S, Vietnam is roughly the size of Italy and is bordered by China to the north and Laos and Cambodia to the west. Dense forest and scrub blanket the mountainous and hilly landscape of the country’s northern sections along the Chinese border.

After the hell-ride from the airport, I met up with the guys from Explore Indochina in the Old Quarter, who offer Minsk-mounted tours for adventurous foreigners to the backcountry. Their trip plan was simple, and very flexible. Our quartet would pick up 125cc Minsk motorbikes in Hanoi and run a big loop heading northwest to Sapa, a focal point for hill tribes in the area. Then we’d hook eastward along the Chinese border, eventually bending back to Hanoi.

Simple, yes, except that they hadn’t clued us in to the miserable road conditions in Vietnam. But they spoke fluent Vietnamese, and had come highly recommended as fearless riders with in-depth knowledge of the area. There was no turning back now…

Baptism By Bike

We set off through the narrow streets of Hanoi surrounded by buzzing bikes, trying to follow the only rule of the Vietnam road that matters – little ones yield to bigger ones. But I can’t think of a better way to explore Vietnam than by bike. The flexibility and mobility of two wheels in a poor country with shoddy infrastructure is unparalleled.

Even if our band is small (two Australians, a Sri Lankan gent and yours truly), we quickly find a common bond in relentless humor and a whatever-will-be approach. Which comes in handy, because as we turn off the main road to take what the guide calls a ‘cool little detour’, we find ourselves plowing straight into a giant field of mud.

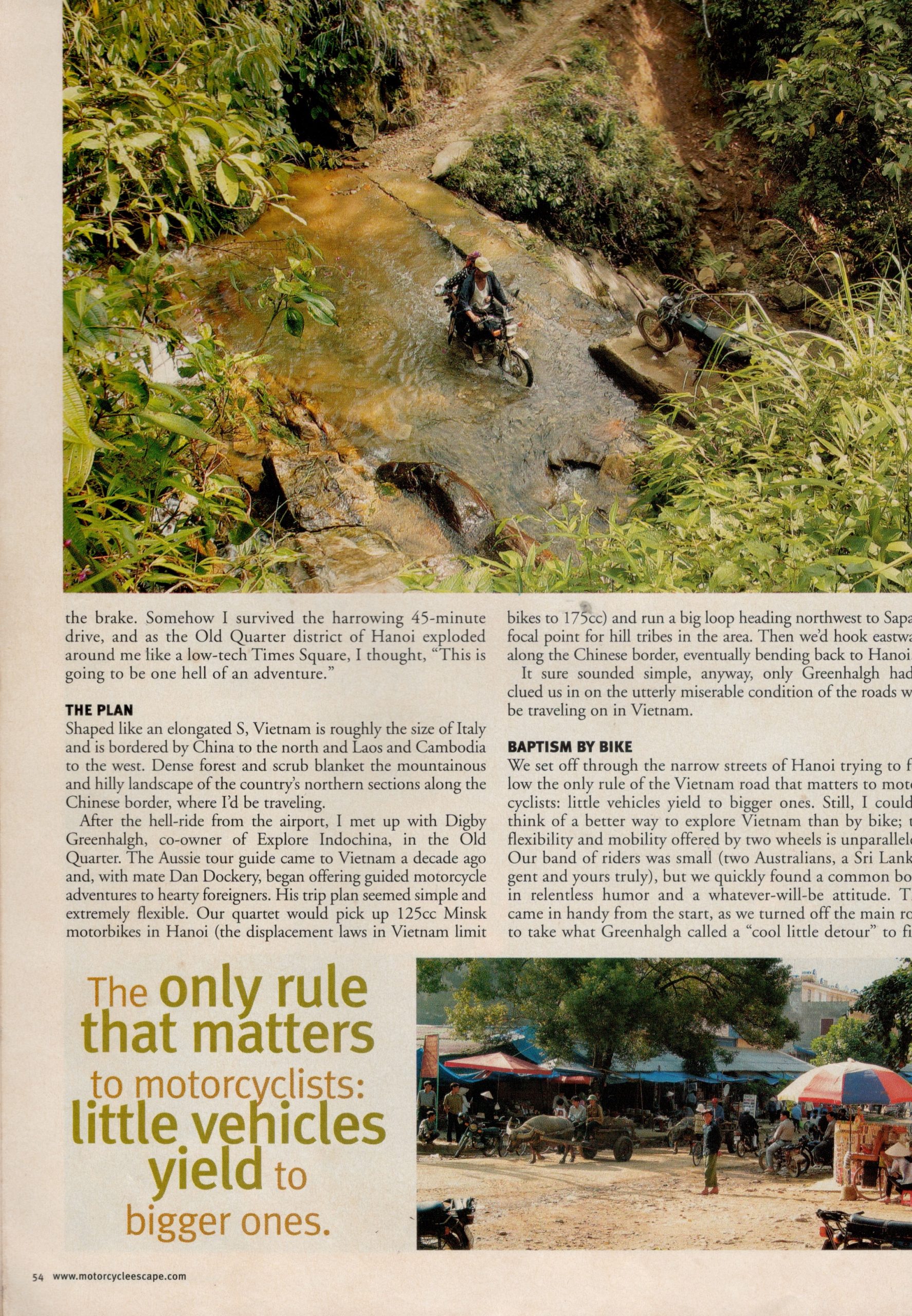

Here, it becomes apparent why the itinerary is so flexible – almost instantly, our bikes sink up to their hubs in belligerent goop, as much as two feet deep. Tiny local women trudging past give us huge smiles, drop their sacks of rice and help push the bikes out of the muck. Red-faced from effort and our self-esteem in the toilet, we’re relieved when a man approaches, chuckling, “No go! Road closed!”. We roll into Nghia Lo at night, rattled but relieved.

Despite their funky appearance and penchant for odd noises, the two-stroke, single-cylinder Minsks are the workhorses of Vietnam; their stout construction and simple technology makes them ideally suited to the unpaved surfaces of this country. And the fact that Minsk repair jobs require nothing more than a paperclip and duct tape makes them priceless on our tour.

Feast For The Senses

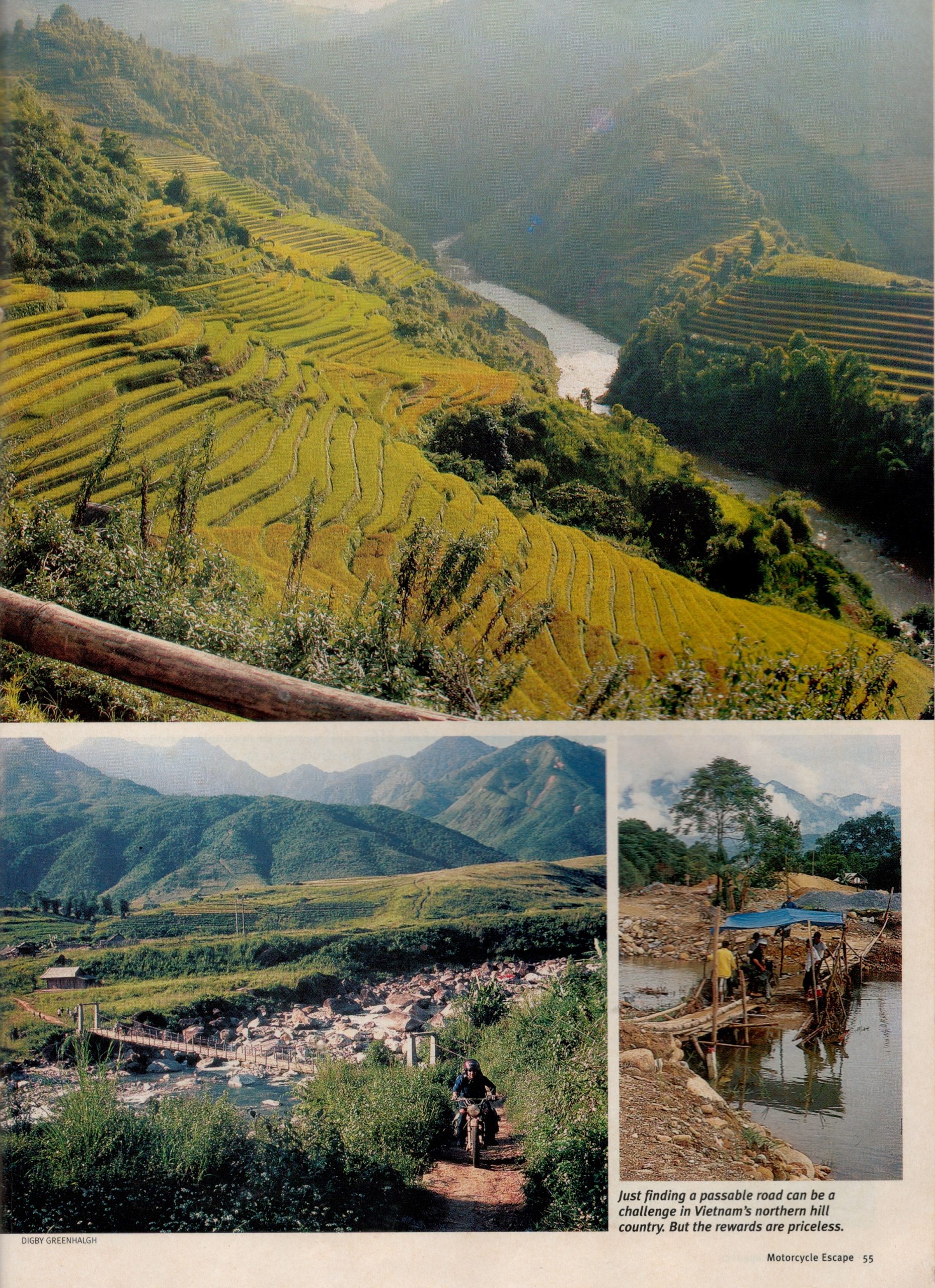

Before my trip, I’d made a pledge to eat like the locals. Which is not a problem – sitting down for dinner that night, I realize that the grilled snake kebab in front of me is the furthest thing from Denny’s I’ll ever experience. It’s quite tasty, too. Although rice is the foundation of the Vietnamese diet, the country’s cuisine incorporates tastes of France, China, and Thailand. Heading north, 10 kilometers of jagged rock brings us to a bridge flung over a flooded patch of ground. Normally, this would be a straightforward crossing, except that the proposed “bridge,” is really more a collection of loose bamboo, resting on boulders on either end. We creep over the swaying framework and then the track solidifies and we’re riding through glorious rice terraces cascading down the valley.

The shaped, green terraces cut into steep hillsides are everywhere in Vietnam. The cycle of planting and harvesting rice is constant, and in September, the harvest is in full swing. There’s amazing terracing down the other side of the pass too, but we don’t linger; nobody wants another midnight ride.

Still, by the time we check into a simple hotel in Than Uyen, it’s dusk. Here, twenty bucks gets us accommodations, a couple of meals and a few drinks, but for the average Vietnamese, it’s two weeks’ pay. I sit on the narrow platform bed and peel off my crusty gear. A fine layer of dirt covers my skin, head-to-toe.

For breakfast, we order what we know, and what we’ve come to know very well in Vietnam is ‘pho’, the national dish of beef noodle soup. Pho is a perfect example of the country’s adherence to the concept of balancing the five flavors: salty, sweet, sour, bitter and hot. The broth is delicious, even if we’re eating it perched on tiny plastic chairs (this furniture is the norm in Nam).

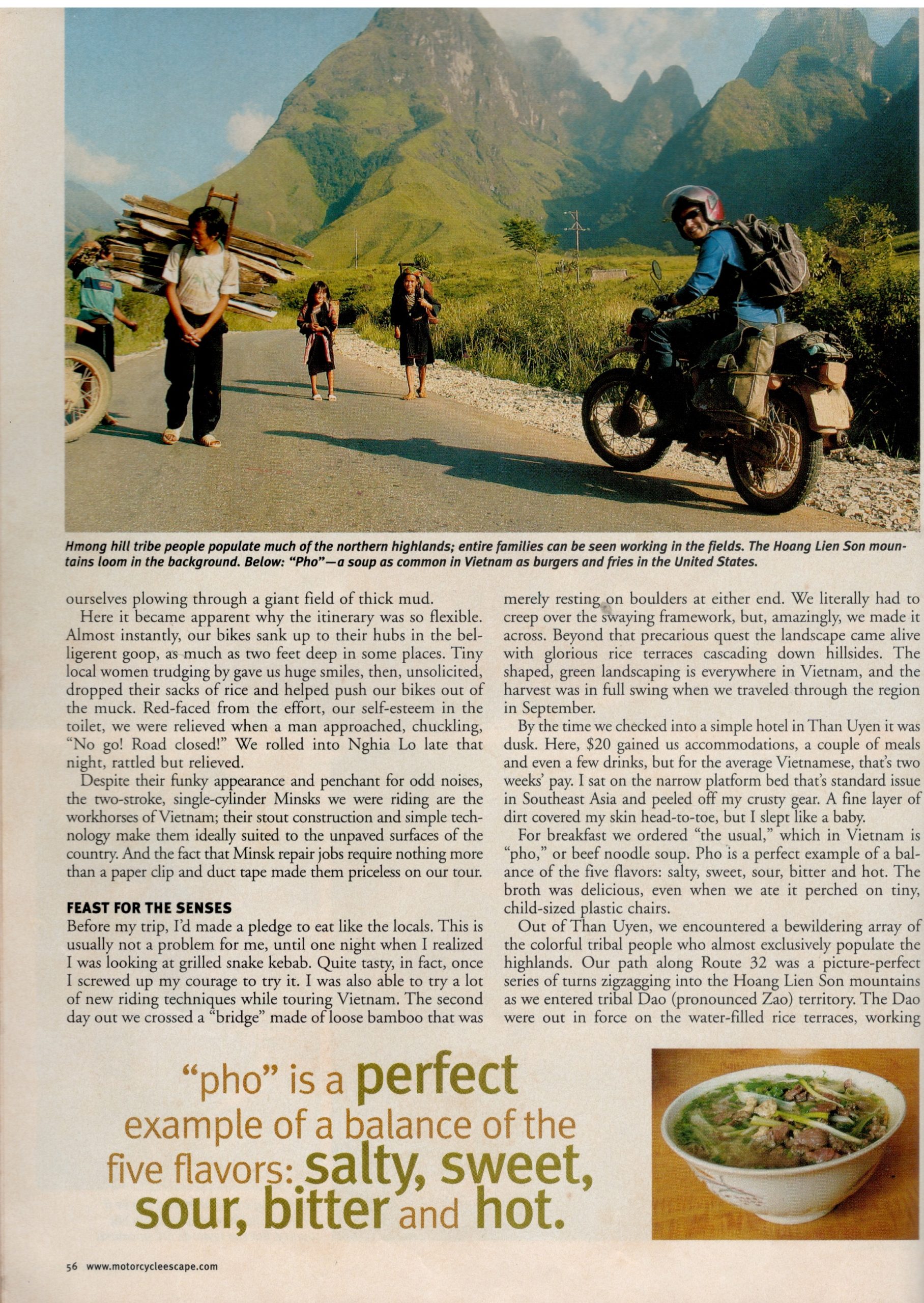

Out of Than Uyen, we encounter a bewildering array of the colorful tribal people who almost exclusively populate the highlands. Our path along Route 32 is a picture-perfect series of turns zigzagging into the Hoang Lien Son mountains, leaving H’mong areas and entering Dao (pronounced Zao) territory. They’re out in force on the water-filled rice terraces, working against the clock to finish harvesting, and their red hats catch the light. The road winds spectacularly up to Tram Ton Pass, with majestic views of Vietnam’s tallest peak, Fansipan Mountain. Next stop, Sapa.

Cliff Diving

Sapa is a magical hill station originally built by the French in 1922 to escape the heat and humidity of lowland Hanoi. With the government now encouraging tourism, foreigners are flocking to the old town to enjoy the rugged scenery and the town’s lively street market, which attracts villagers from surrounding hills. Embroidery and jewelry of the H’mong and Dao are on display, and the sight of dozens of minorities in traditional clothing is unforgettable. Close up, the Red Dao attire is stunning. Their multi-layered garments are beautifully decorated with colored scraps of cloth and all the females wear embroidered red headresses.

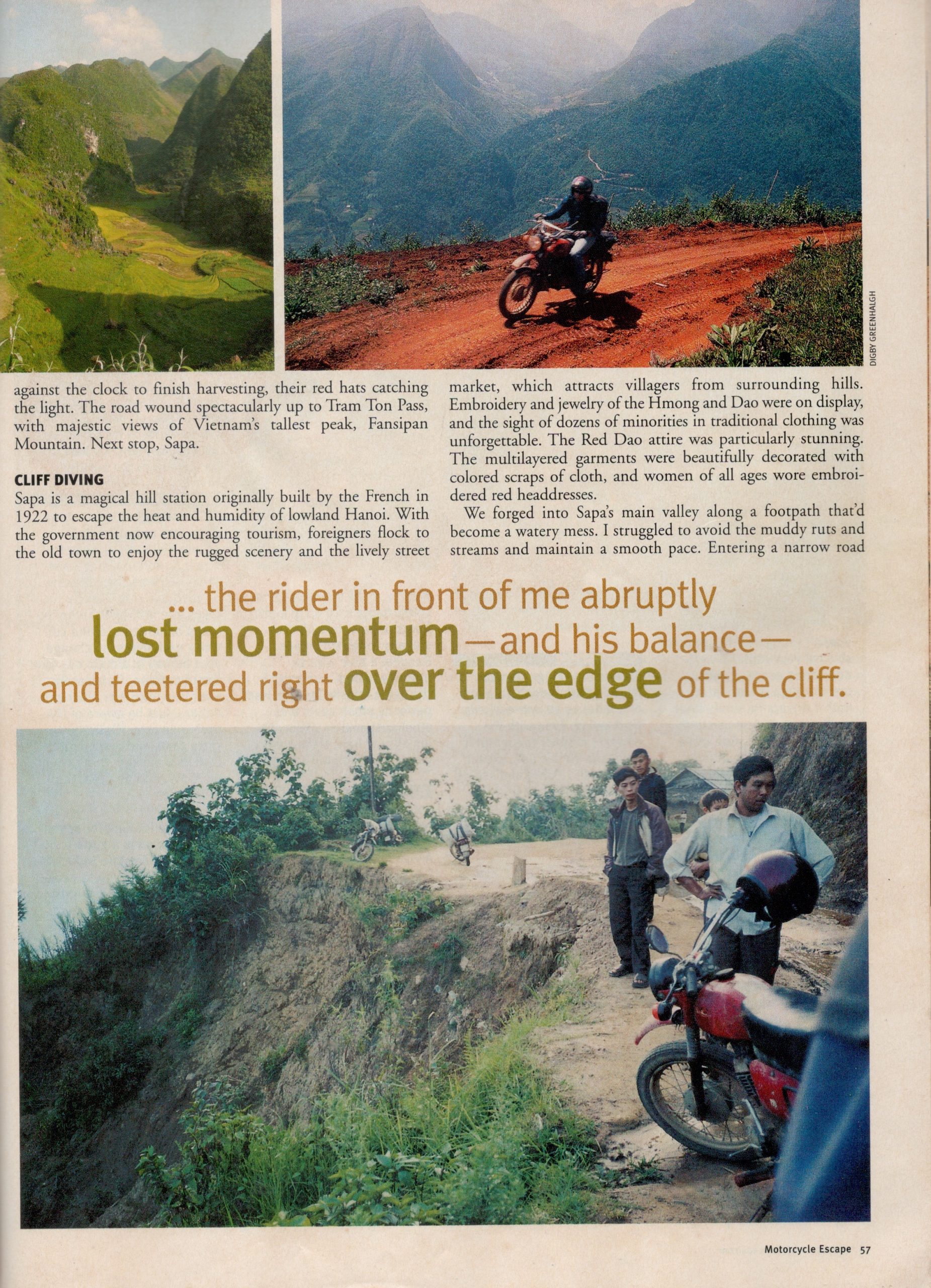

We forge into Sapa’s main valley along a footpath that’s become a watery mess. I struggle to avoid the muddy ruts and streams and maintain a smooth pace. Entering a narrow road cut into the mountainside, it’s hard not to be conscious of the valley hundreds of feet below. And it’s here that I witness the cliff dive of the rider.

As I look over the edge, a single hand stretches up from behind a bush down the ravine. Then, a weak groan – ‘over here!’ Relief floods over me as local villagers gather to watch the fallen man’s riding partner slide down a dirt chute and help his injured friend to safety (he’d only broken an ankle). Unbelievably, a group of villagers is somehow dragging the twisted bike wreckage up from the brush. One of the spectators offers, “This is fifth rider to fall in two year!”, but it’s still amazing that the rider’s even alive.

Of Refrigerators, Moonshine And Markets

At the Nan Ma pass, mudslides have washed out large chunks of the path and we have to pick our way through liquidy troughs. A dark crust cakes our legs. To add insult to injury, a grinning local on a moped weaves past, dressed in khaki shorts, a white shirt and sandals. There’s not a speck of dirt on him, and as he sails by, we can’t help but notice the full-size refrigerator strapped across the back.

Humbled and grubby, we check into a cheerless Soviet-style hotel in Xin Man, looking forward to a hot meal. I have vague memories of dinner that night, but one of the highlights involves a transparent vat of rice liquor known as ruou (pronounced zeal). Normally this stuff contains some dead creature (such as a crow) that’s supposed to imbue it with certain qualities, but tonight’s version is the less exotic corn variety.

We’re minding our own business when four young men invite themselves over to our table. It’s a brave show when you consider that they speak approximately seven words of English. They place a thimble-size glass in front of me, filling it with translucent liquor. I don’t want to be rude, and soon the tiny place is shaking with the happy cries of our broken language… “Won, Too!” and “Hokay!” from them, followed by an enthusiastic “Xin Chao!” from me. I’d noticed that some tours in Hanoi touted ‘authentic meals with local people’ and I imagine that I’m having an authentic experience right now.

At 7am, the Sunday market in Xin Man is already filled with hilltribe traders from surrounding villages. Picking our way through the crowd, we’re met with either confused stares or warm smiles – the way you’d look at a baby or a puppy. The event consists of several narrow alleys lined with wooden stalls offering basic sundries, but its flavor is other-worldly, with all the participants adorned in magnificent costumes.

Chaperoned

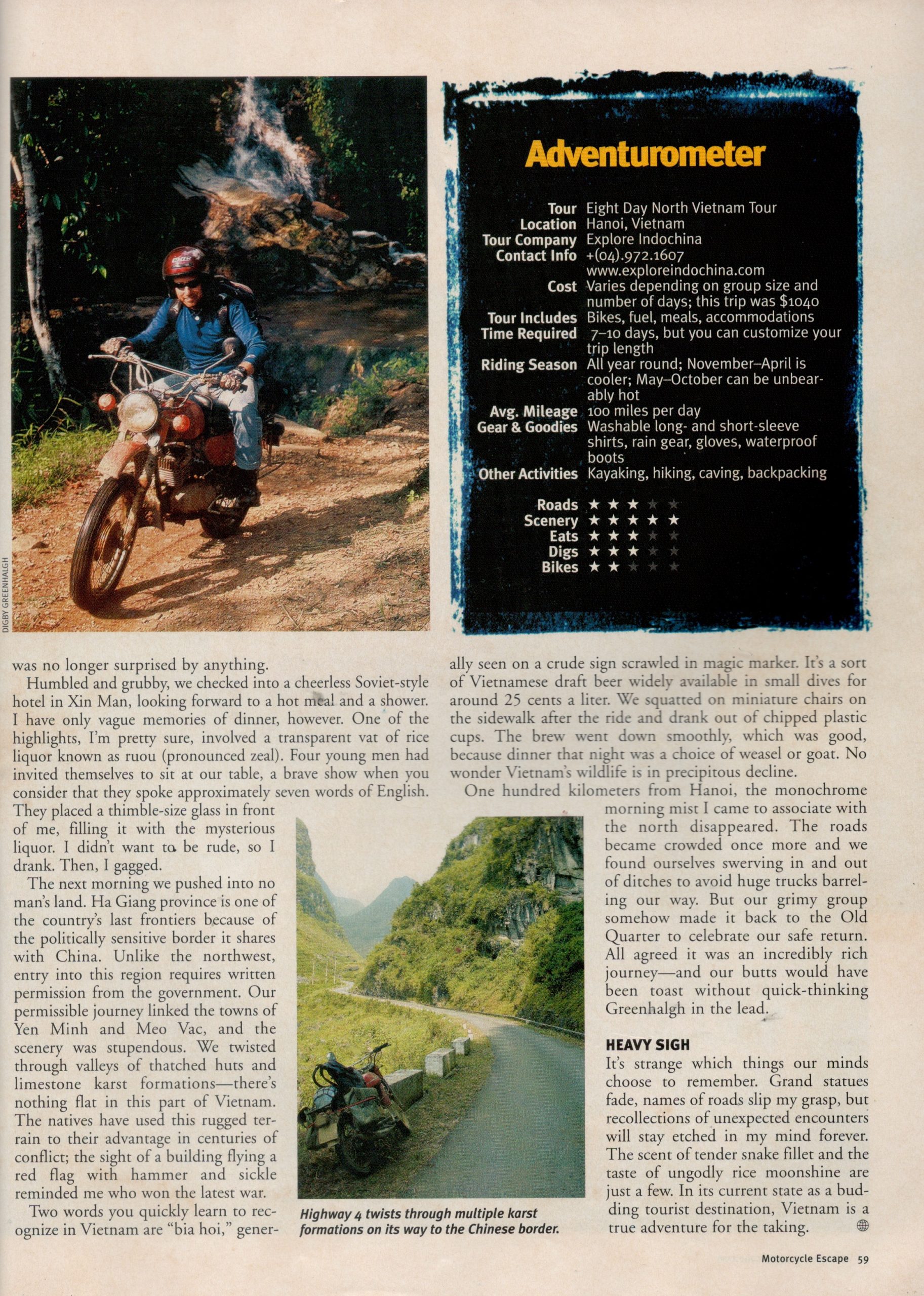

Ha Giang province is one of the country’s last frontiers because of the politically sensitive border it shares with China. Unlike the northwest, entry into this region requires written permission from the government. Our permissible journey links the towns of Yen Minh and Meo Vac, and the scenery is stupendous. We’ve been twisting through valleys of thatched huts and limestone karst formations – there’s nothing flat in this part of Vietnam. Passing by a building flying a red flag with a hammer and sickle, though, I realize this country still goes by the name Socialist Republic of Vietnam. It’s a weird reminder of who won the war.

Two words you learn to recognize in Vietnam are ‘bia hoi’, generally seen on a crude sign scrawled in magic marker. This sort of Vietnamese draft beer is widely available in small dives for around 25 cents a liter. We squat on miniature chairs on the sidewalk, and drink out of chipped plastic cups. The brew goes down smoothly, which is good, because dinner that night is a choice of weasel or goat. No wonder Vietnam’s wildlife is in precipitous decline.

One hundred kilometers from Hanoi, the morning monochrome mist I came to associate with the north has disappeared. The roads are also more crowded and we find ourselves swerving into ditches to avoid huge Hyundai trucks barreling our way. Our grimy group somehow makes it through back to the Old Quarter, and squatting on the beloved plastic stools with Digby, we celebrate our safe return. It’s been an incredibly rich journey – and our butts would have been toast without the quick-thinking Aussie guide in the lead.

Heavy Sigh

It’s strange which things our minds choose to remember. Grand statues fade, names of roads slip through our grasp, but recollections of unexpected encounters with local inhabitants and everyday simple scenes will stay etched in my mind. Scenes like the taste of tender snake fillet on a patio in Nghia Lo, Vietnam, for example. In its current state as a a budding tourist destination, Vietnam is a true adventure for the taking.

More Articles

ADV Rider Magazine

by Sean Goldhawk

Rider Magazine

by Perri Capell

TIME Magazine Asia

by Kay Johnson