FHM

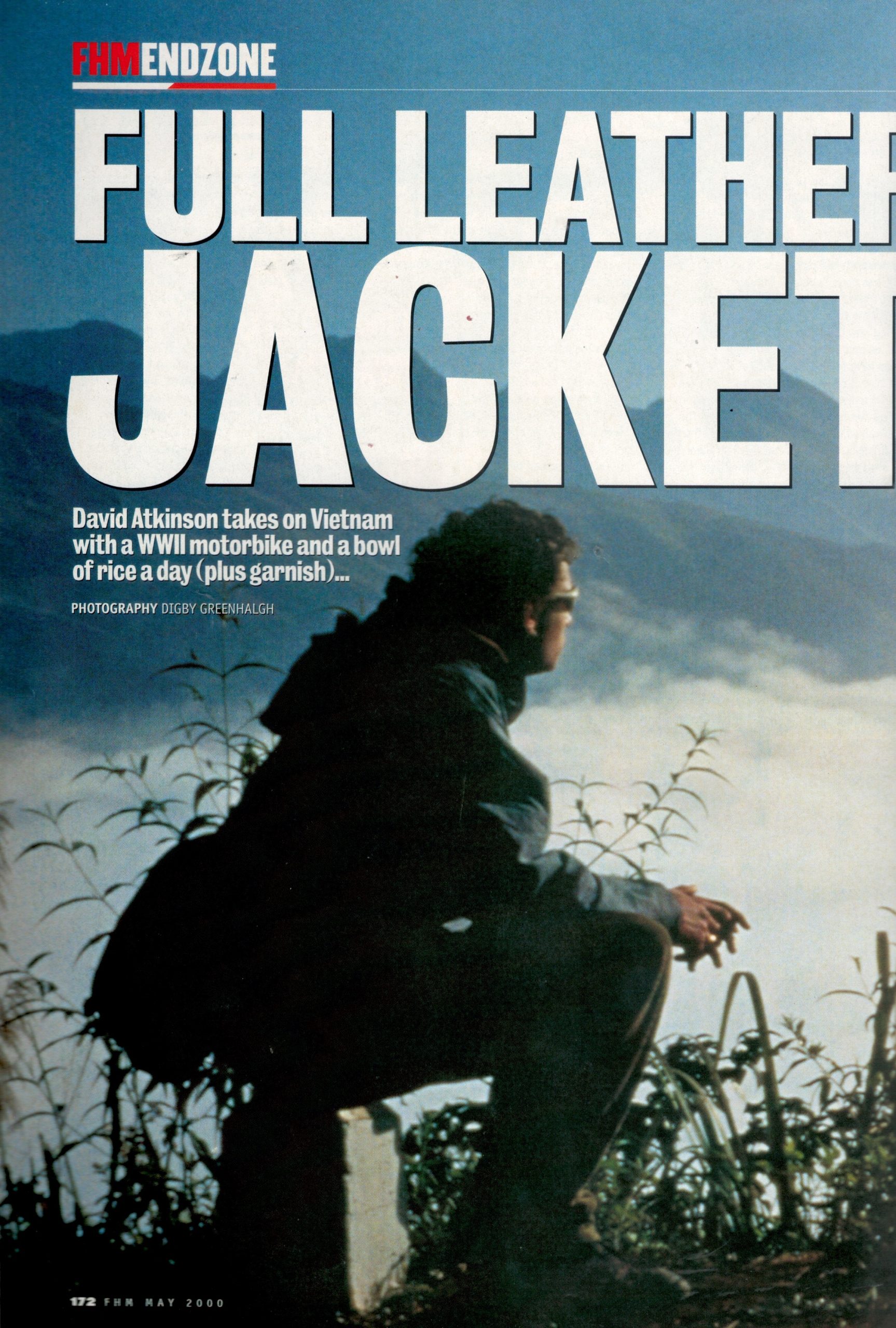

Full Leather Jacket

by David Atkinson

The Open Road

I love the thrill of the open road shades on, foot to the floor, cruising with the stereo blaring and my best girl by my side, pointing out interesting bits of roadkill. Sadly, though, this image just isn’t an option in Vietnam. For a start, there are few “open roads”, car-rental is a nightmare, and city roads are so packed that cabs, as we know them, are pointless. This is a place where, if you need a ride, you flag down a passing motorbike, slip them 5,000 Vietnamese dong and get on the back (this trans- lates to about 50 cents Australian, tempting scores of brilliant gags about how pitiful Vietnamese dongs are). But I digress… So if you want to avoid the hordes on the state-approved backpacker trail from Ho Chi Minh City to Hanoi, as did I, then taking off into the mountains on a motorbike is the way to go. So, keen to avoid traditional tourist traps and see the real ‘Nam, I found myself signing on for a “Minsk Club” tour (named after the Minsk, the pre-World War II Russian 125cc motorbikes they use) from Hanoi to the principal city of the far north, Ha Giang.

Minsk Club claims to avoid the trappings of mass tourism, such as packaged tours and insulation from creepy-crawlies, in favour of tailored packages to remote rural locations. Immediately dubious about this—what kind of nutter boasts of not avoiding creepy-crawlies?—I pushed on with the heady scent of adventure in my nostrils.

The man behind the club is Sydney-born Digby Greenhalgh, a 30-year-old photographer who moved to Vietnam as the country was opening its doors to foreigners in 1994. Since then he’s made over 100 trips, and compiled a comprehensive, albeit unpublished, motorbike guide to the nation. The Vietnamese call the Minsk “con trau gia”, or “old buffalo”, as they’re low on efficiency, high on fuel consumption, and extremely robust. “There are only a certain number of things that can go wrong with a Minsk because there are only a certain number of parts in it,” Digby explained. “I’ve seen a squashed Coke can fashioned into a clutch plate. I’ve used strips of a truck inner tube to keep the front suspension and wheel from falling off, and I’ve used my numberplate as a brace to hold a broken clutch lever.

“Basically, if you have a rock and a stick then you can repair a Minsk. No fancy parts, just steel, rust, and mud.” He made no bones about the fact that his trips are best suited to those with prior biking experience as—weather-wise—the going can be tough. “I make it clear to people that our route is entirely flexible, that they will have to work, that I am not going to hold their hand, and that we will have to overcome difficulties,” he said. “I show them the most interesting route, maybe taking them to places only 10 to 100 white people have ever been.” Maybe not for long…

Despite a niggling scepticism triggered by scant knowledge of Vietnam’s history—I’m pretty sure the French ponced about the place for a while—I took Digby’s assertion as fact. By his maps it is, frankly, bloody isolated up there; plus, I thought it unwise to alienate my guide in a Third World nation where I didn’t speak the language.

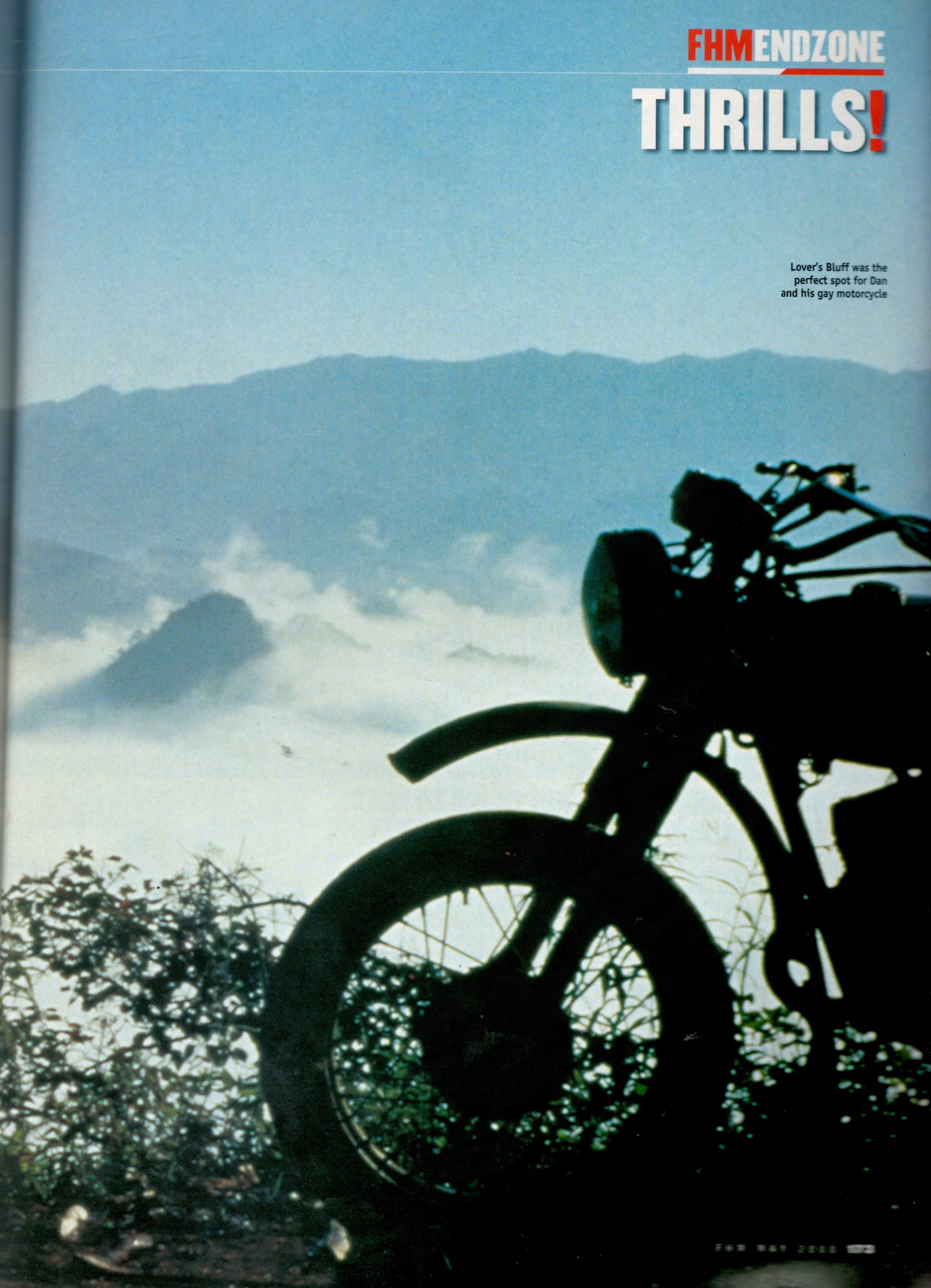

Climbing North

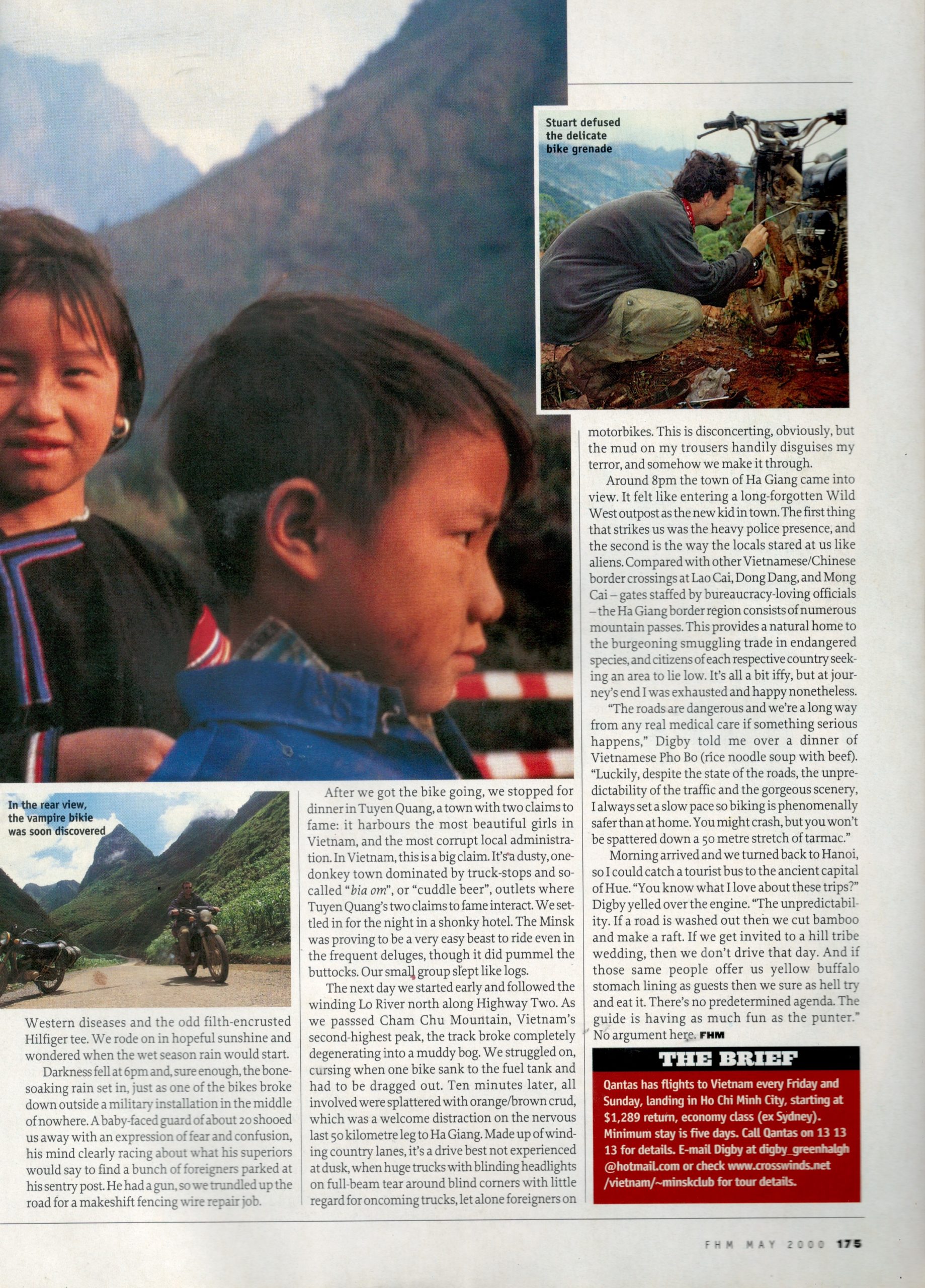

We joined Highway Two near Hanoi’s Noi Bay Airport and began the slow climb north. The road was disintegrating steadily from tarmac to rocky track, and the scenery shifting from urban sprawl to lush rice paddies. As we progressed at a steady 35 kilometres per hour, attempts to overtake lumbering trucks were replaced by attempts to overtake lumbering water buffalo. Ahead of us lay the misty silhouette of the mountains, and some of the most spectacular scenery in South-East Asia. The area is populated by ethnic-minority tribes. Many, apparently, still live as they did 1,000 years ago—albeit with new Western diseases and the odd filth-encrusted Hilfiger tee. We rode on in hopeful sunshine and wondered when the wet season rain would start.

Darkness fell at 6pm and, sure enough, the bone-soaking rain set in, just as one of the bikes broke down outside a military installation in the middle of nowhere. A baby-faced guard about 20 shooed us away with an expression of fear and confusion, his mind clearly racing about what his superiors would say to find a bunch of foreigners parked at his sentry post. He had a gun, so we trundled up the road for a makeshift fencing wire repair job.

After we got the bike going, we stopped for dinner in Tuyen Quang, a town with two claims to fame: it harbours the most beautiful girls in Vietnam, and the most corrupt local administration. In Vietnam, this is a big claim. It’s a dusty, one-donkey town dominated by truck-stops and so- called “bia om”, or “cuddle beer”, outlets where Tuyen Quang’s two claims to fame interact. We settled in for the night in a shonky hotel. The Minsk was proving to be a very easy beast to ride even in the frequent deluges, though it did pummel the buttocks. Our small group slept like logs.

The next day we started early and followed the winding Lo River north along Highway Two. As we passed Cham Chu Mountain, Vietnam’s second-highest peak, the track broke completely degenerating into a muddy bog. We struggled on, cursing when one bike sank to the fuel tank and had to be dragged out. Ten minutes later, all involved were splattered with orange/brown crud, which was a welcome distraction on the nervous last 50 kilometre leg to Ha Giang. Made up of winding country lanes, it’s a drive best not experienced at dusk, when huge trucks with blinding headlights on full-beam tear around blind corners with little regard for oncoming trucks, let alone foreigners on motorbikes. This is disconcerting, obviously, but the mud on my trousers handily disguises my terror, and somehow we make it through.

Around 8pm the town of Ha Giang came into view. It felt like entering a long-forgotten Wild West outpost as the new kid in town. The first thing that strikes us was the heavy police presence, and the second is the way the locals stared at us like aliens. Compared with other Vietnamese/Chinese border crossings at Lao Cai, Dong Dang, and Mong Ca —gates staffed by bureaucracy-loving officials—the Ha Giang border region consists of numerous mountain passes. This provides a natural home to the burgeoning smuggling trade in endangered species, and citizens of each respective country seeking an area to lie low. It’s all a bit iffy, but at journey’s end I was exhausted and happy nonetheless.

Dinner With Digby

“The roads are dangerous and we’re a long way from any real medical care if something serious happens,” Digby told me over a dinner of Vietnamese Pho Bo (rice noodle soup with beef). “Luckily, despite the state of the roads, the unpredictability of the traffic and the gorgeous scenery, I always set a slow pace so biking is phenomenally safer than at home. You might crash, but you won’t be spattered down a 50 metre stretch of tarmac.”

Morning arrived and we turned back to Hanoi, so l could catch a tourist bus to the ancient capital of Hue. “You know what I love about these trips?” Digby yelled over the engine. “The unpredictability. If a road is washed out then we cut bamboo and make a raft. If we get invited to a hill tribe wedding, then we don’t drive that day. And if those same people offer us yellow buffalo stomach lining as guests then we sure as hell try and eat it. There’s no predetermined agenda. The guide is having as much fun as the punter.” No Argument here.

More Articles

ADV Rider Magazine

by Sean Goldhawk

Rider Magazine

by Perri Capell

TIME Magazine Asia

by Kay Johnson