By Any Means by Charley Boorman

Vietnam by Minsk

by Charley Boorman

Vietnam by Minsk

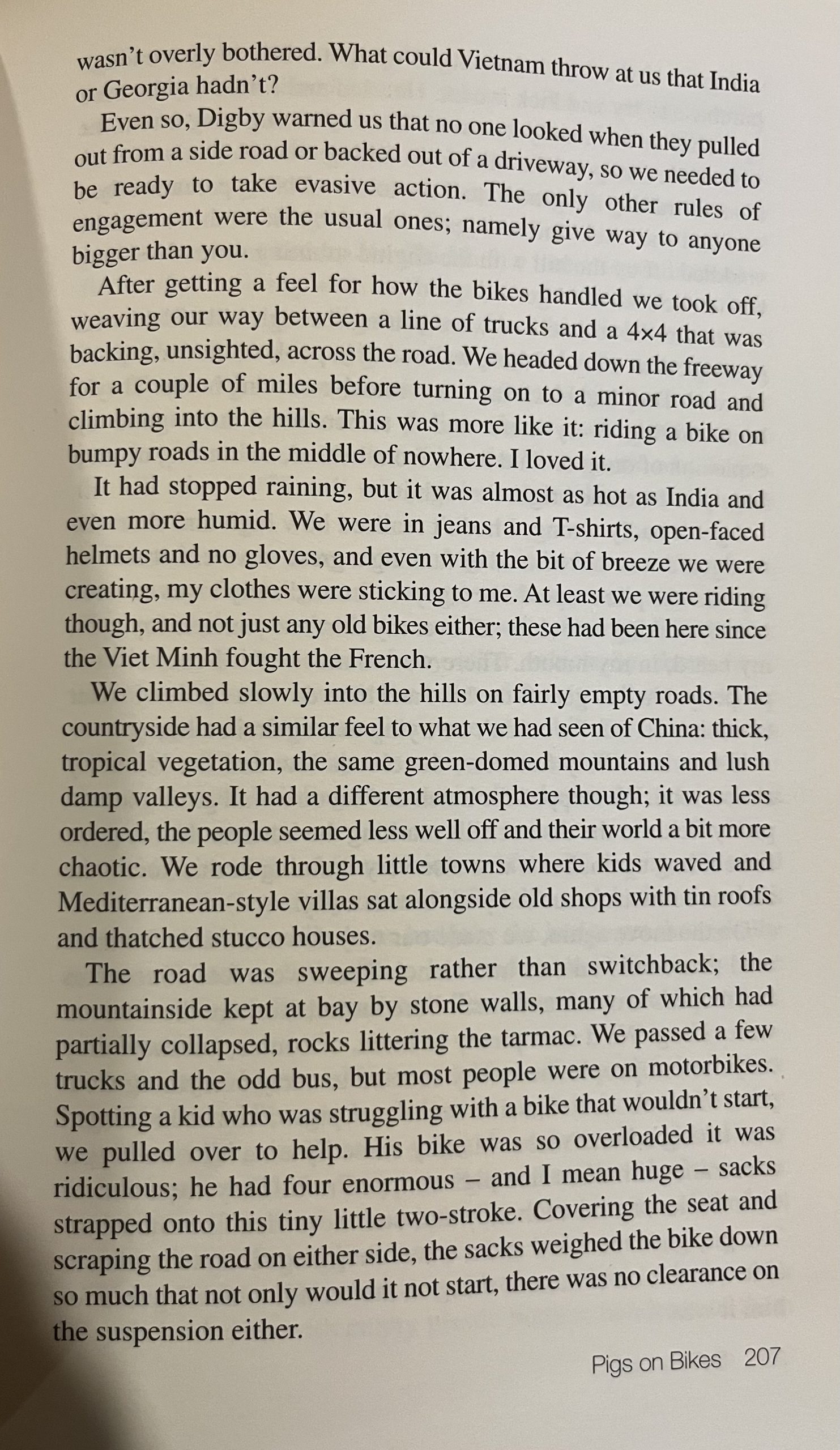

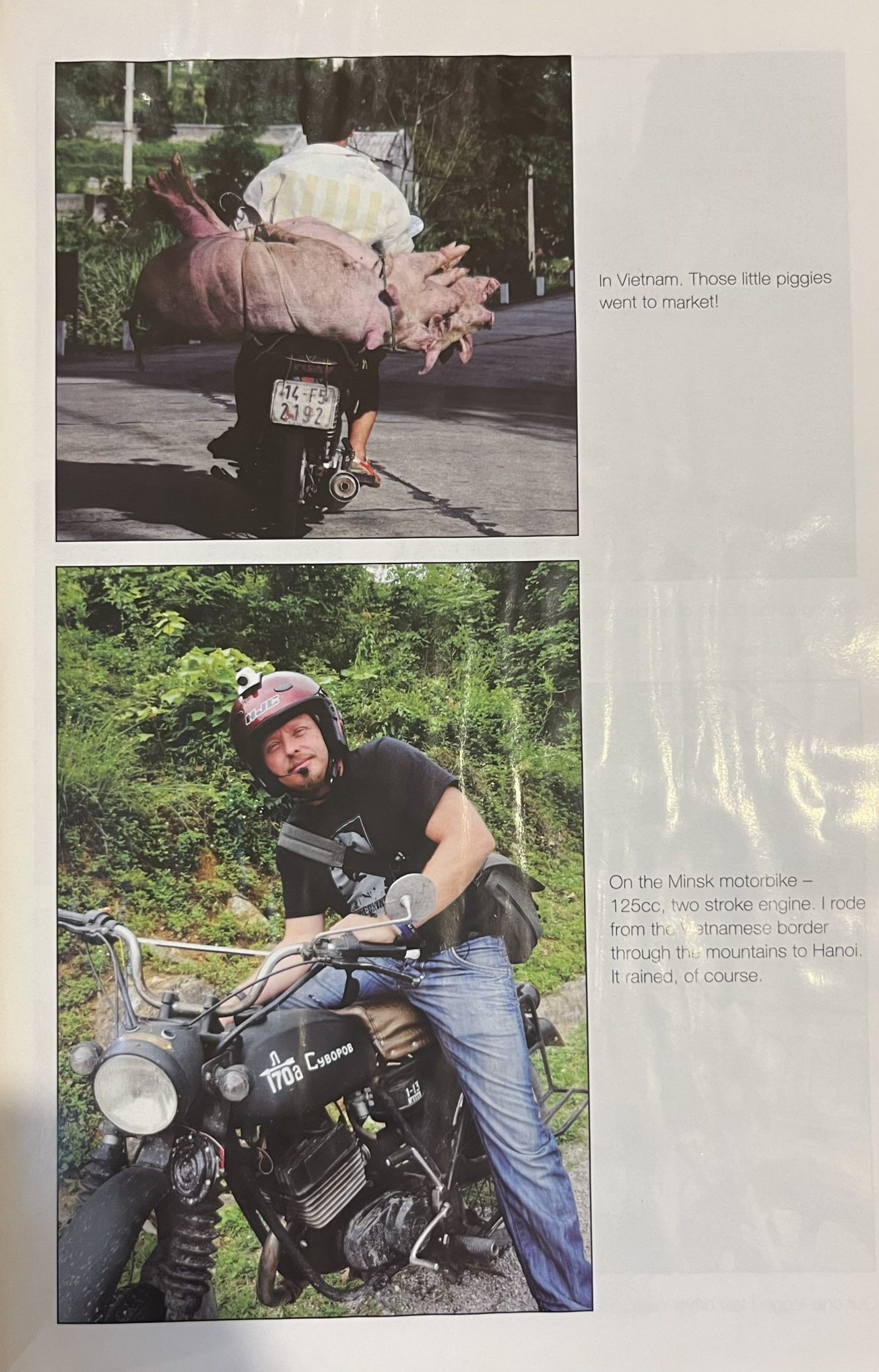

At last we were all standing on Vietnamese soil. And we had motorbikes waiting. I’d already spotted them: two military green Minsk motorbikes that had been brought to the border by an Australian called Digby, who runs a tour company in Hanoi. They looked like a couple of World War Two scramblers with knobbly tyres and chunky frames, the serial numbers painted on their petrol tanks. The bikes were named after the city of Minsk in Belarus where they were made. First produced in 1951, the factory had been manufacturing bicycles since 1945 and decided to expand their market with a motorcycle. They were simple and reliable and ended up being exported all over the world.

Digby told us there was a freeway that linked the border crossing here at Dong Dang with the capital, but the last thing we wanted was to sit on some manic motorway. He suggested a route through the northern hills instead.

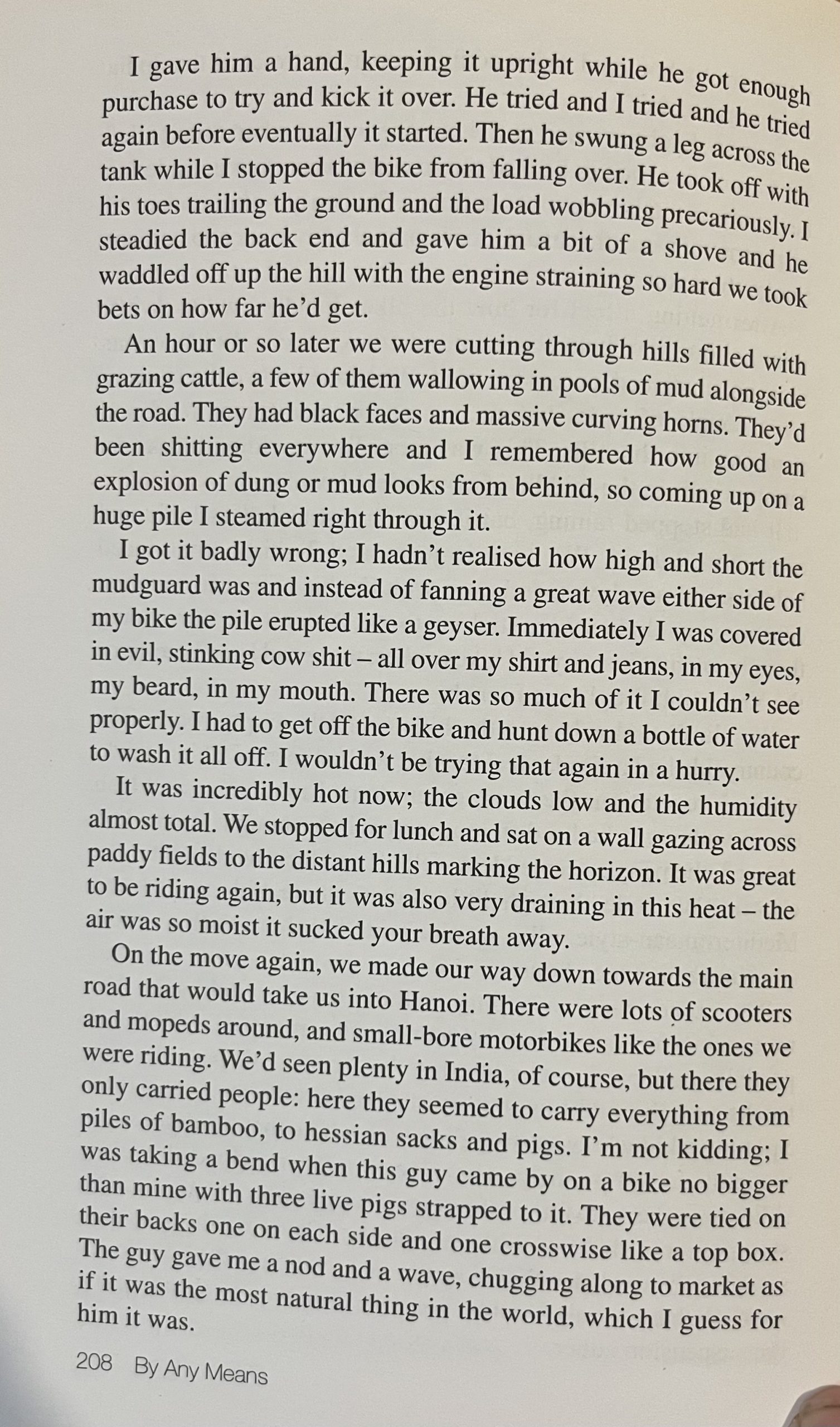

It was great to be riding again, back in control of my own destiny after a succession of other people’s vehicles. The bikes, which had been built in the 1950s, were 125cc and being two-strokes there was no engine braking: in fact there didn’t seen to be much braking of any description. They had the old drum system that people like Geoff Duke used to use and when I tried them they didn’t offer much. But then they didn’t go very fast either and we were both experienced riders. The gearing was one down and three up; there was no battery, but the most important part was the horn. Everyone in Vietnam rode on the horn — you were expected to hoot and be hooted at; that’s the way it was. If for any reason the horn stopped working we’d have to pull over and fix it.

More Articles

ADV Rider Magazine

by Sean Goldhawk

Rider Magazine

by Perri Capell

TIME Magazine Asia

by Kay Johnson