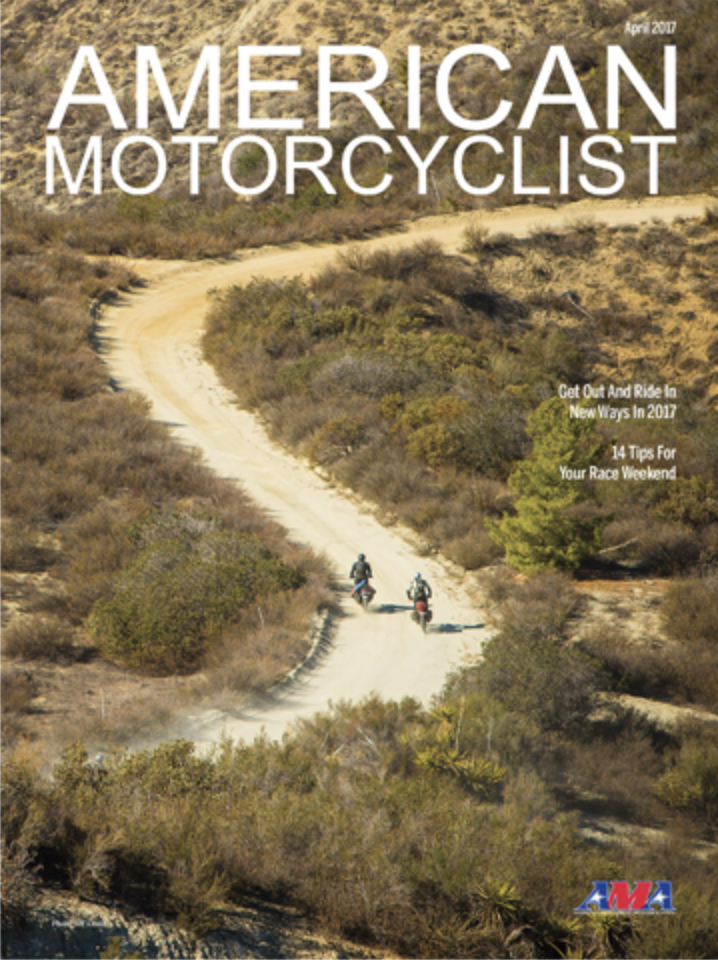

American Motorcyclist

Vietnam Revisited

by Dr. Gregory W. Frazier

Revisited

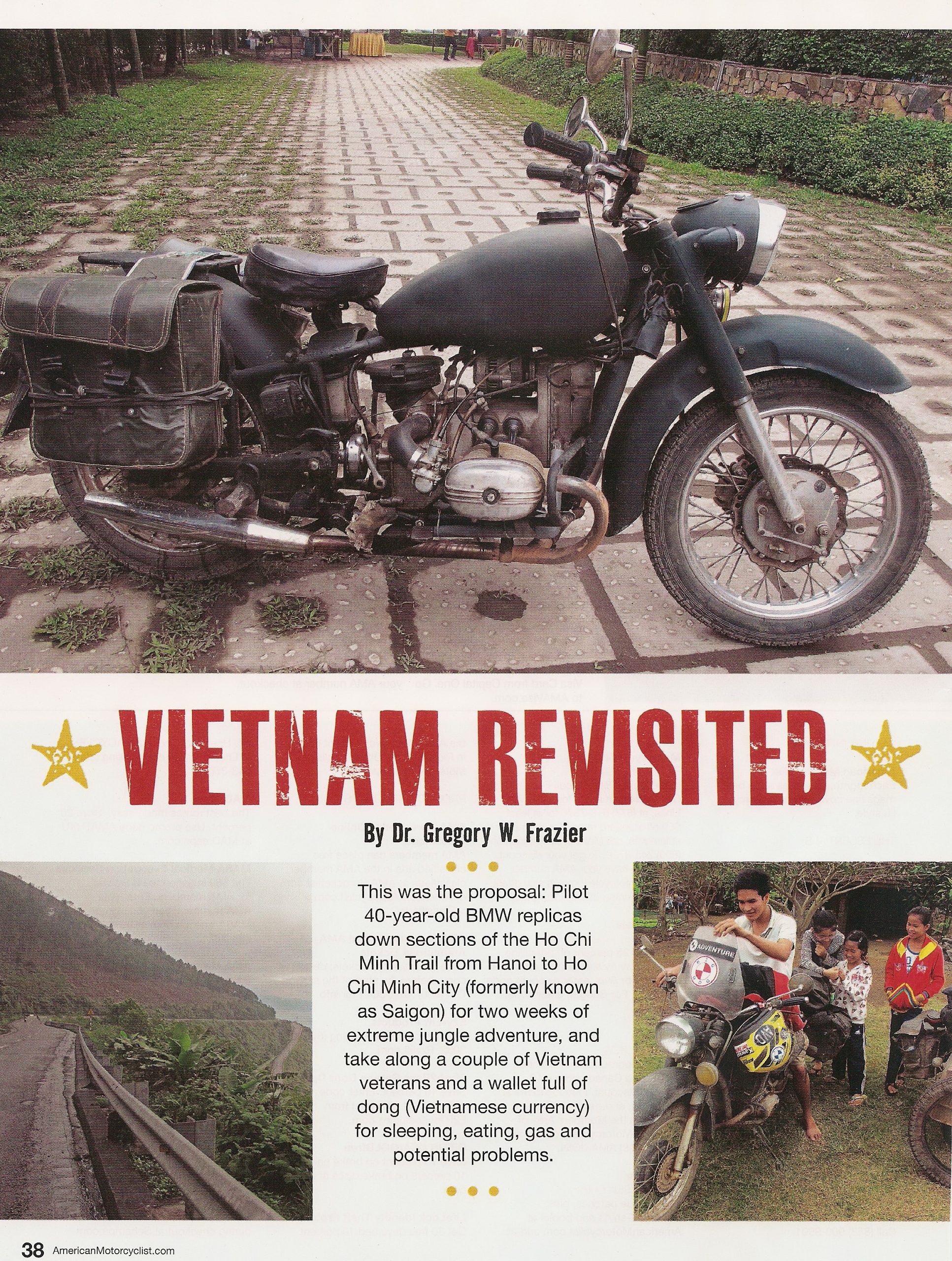

This was the proposal: Pilot 40-year-old BMW replicas down sections of the Ho CHi Minh Trail from Hanoi to Ho Chi Minh City (formerly known as Saigon) for two weeks of extreme jungle adventure, and take along a couple of Vietnam veterans and a wallet full of dong (Vietnamese currency) for sleeping, eating, gas and potential problems. It was submitted by the established Hanoi-based Explore Indochina company (www.exploreindochina.com). Like a hungry trout, I was reeled in by their concept.

Explore Indochina’s owners bought nearly 60 Russian military Ural motorcycles left over after the Vietnam War (known as the “American War” in Vietnam). These copies of early 1940s BMWs ranged from junk to barely running. With Vietnamese ingenuity they shook the fleet up in a bag, modified what came out with Japanese car parts, such as 12-volt alternators and shock absorbers, and offered a 650cc motorcycle in a country where big-displacement imported motorcycles can be taxed at two to three times their U.S. purchase price.

This high import tax results in 99.99 percent of the millions of motorcycles in Vietnam being 125cc or smaller in engine displacement. (It should come as little surprise that on my two previous adventures in Vietnam, the motorcycles used were 125cc Minsk two-stroke models.)

The opportunity to attempt riding 2,000-3,000 kilometers from north to south using antique copies of BMWs put my personal adventure needle in the “extreme” category. Taking along some trusted acquaintances who had not seen Vietnam for more than 40 years allowed me a chance to see the country through their eyes.

Going into the jungles with no GPS and no emergency satellite location devices meant we would be on our own, cut from the cyber tethers that govern much of our daily lives. It would be an adventure with a capital A.

Launch

Our small expedition team met in Hanoi, signed paperwork, and managed to escape the throngs of small motorcycles, trucks and buses unscathed. Imagine Hanoi as an anthill with gasoline tossed on it and lit, with each ant having a horn, and you get a sense of driving in downtown Hanoi from 6 a.m. until 10 p.m.

We left the ugliness of the Highway 1 (the main car, truck and bus route between Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City), within a kilometer of our start point and vectored toward the adjoining border of the country of Laos. Our next two weeks were on and off parts of the Ho Chi Minh Trail as we traveled south.

While there was never a single Ho Chi Minh Trail, and much of the trail network was in Laos, many of the tracks and feeder trails or roads were along the western border of Vietnam. It was these Vietnamese sections we sought —those well off the tourist routes of today.

We found most of the roads along the border well-marked and in reasonably good condition. Road construction and mudslides required some detours through villages or over jungle tracks. It was not unusual to drive through flocks of domesticated ducks or around cows walking on the roads. Chickens were the hardest to avoid, three committing suicide by running into the moving Urals. The biggest animal to try knocking one of our riders off their motorcycle was a dog. It learned there was little give to the cylinder sticking out of the Ural engine and became another fatality (and likely stew

meat in the village that night).

The nearly half-century-old Urals were fun, each having its own personality and issues with regard to everything from starting to oil containment. Our group decided to pool our dong to take along a well-trained Vietnamese mechanic and a saddlebag filled with spare parts. He kept the old clunkers rolling, whether by changing a flat tire, sorting out an electrical gremlin or replacing a broken driveshaft bolt. Our own BMW-trained mechanic later admitted that it was one of our smartest decisions.

Different But Same

The Vietnam of today was far from the explosion-filled jungles of 40 to 50 years ago, and yet in ways strikingly similar. The rice paddies were still everywhere, as were men and women in conical straw hats carrying produce suspended from bamboo supports heavily weighing on their shoulders. Smiling, friendly and often English-speaking Vietnamese people would frequently engage us in curious conversations recognizing we were foreigners or using what they seldom saw, big motorcycles.

The green jungle had grown over much of the devastation caused by the war, but not all. Scorched sections on mountainsides still could be seen where, 40 years earlier, napalm had burned the lush foliage to the ground. The jungle was slowly eating away at the dead earth and we guessed that in another 10-15 years it would recapture what had been lost to the chemicals.

At one small war museum deep in the jungle, we viewed black and white photographs of workers building roads through the jungle, the roads being parts of the Ho Chi Minh Trail. One photograph showed women workers carrying baskets of rocks while overhead an American jet was coming in for a strafing or bombing run on the nearly completed road. The same museum displayed several military trucks and bulldozers used to build the roads, each with Russian letters stamped on their engines and metal body parts. It was a harsh reminder of who was fighting whom 40 years earlier. And then we reminded ourselves that we were riding on abandoned Russian army motorcycles, likely used as courier or delivery vehicles.

On one occasion, a Vietnamese guard in front of a government office chatted with one of our war veterans. With broken English and limited Vietnamese, the two discovered both were in the war on opposite sides, but the language barrier prevented them from reaching a point where either could claim bullets had been traded. They parted with a friendly handshake and smiles, the medicine of time curing possible hostile memories. Our accommodations ranged from three-star hotels with slow Internet connections to mattresses on the floor in a common room in remote mountain areas. Food was always a surprise, ranging from what might have been dog bone soup to a stop at one of the two Kentucky Fried Chicken restaurants in Ho Chi Minh City. It was a surprise to see a restaurant selling Texas-style BBQ, but we stopped only to take a photograph, preferring to try the local fare.

We found gas easily, and the road signs were readable. The thick jungles fed by rain and streams along the Laos border were a stark contrast to the upscale beach resorts where foreigners sunned on sand beaches. We skipped most of the popular tourist stops, such as crawling through underground tunnels or visiting major war museums. We were in Vietnam to pilot motorcycles through relatively unseen areas searching for roads and tracks, not to visit modernized tourist destinations. A few stops in major tourist areas like Hoi An and Nha Trang were refreshing, but we found our lust for jungle motorcycle adventures bubbling after a single night in each tourist town.

Clouds As Well As Mystery

Vietnam remained shrouded in clouds as well as mystery. Passing through a government-restricted area near the border of Laos where photographs were forbidden, we noted a new airfield being constructed, well protected in a valley between two ranges of mountains. It was obvious it would not be a commercial landing zone because there were no major towns or tourist attractions nearby, merely jungle and a few thatched huts. The Vietnamese military, ever wary, was preparing another installation.

At the opposite end of the spectrum were the numerous motorcycle tour guides in several tourist towns displaying “Easy Rider(s)” embroidered on their jackets, printed on their business cards and displayed on their motorcycles. Following one small motorcycle through a jungle track well away from a city, | smiled when | saw the driver was wearing a copy of a Harley-Davidson sweatshirt from a dealer near my office in the United States.

Vietnam by motorcycle can be a pampered organized motorcycle tour using your own motorcycle or an extreme expedition pushing the definition of your personal motorcycle-adventuring envelope. Neither offers a place to learn to ride a motorcycle, but both can provide an environmental motorcycling taste not found elsewhere on the planet.

More Articles

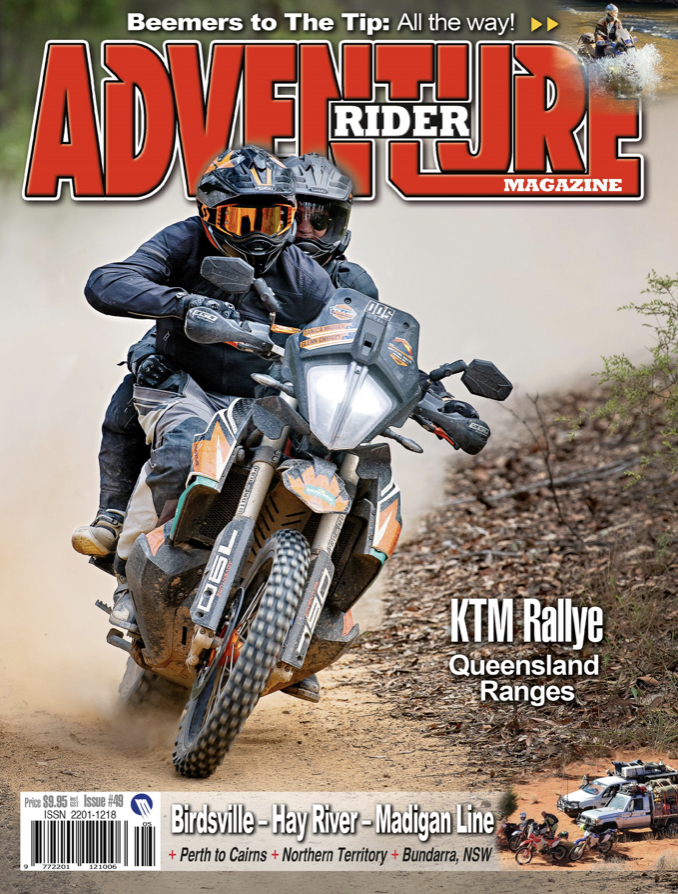

ADV Rider Magazine

by Sean Goldhawk

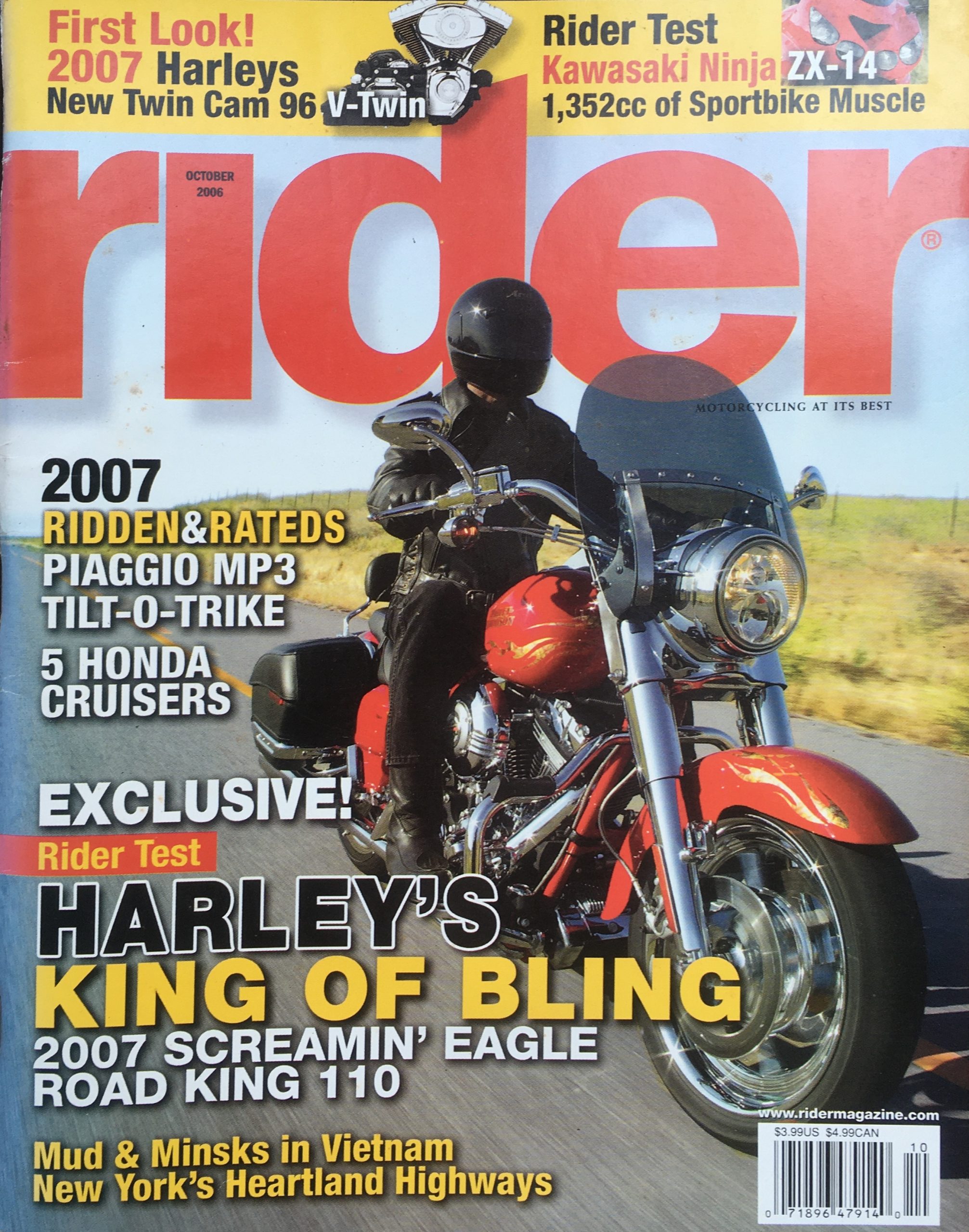

Rider Magazine

by Perri Capell

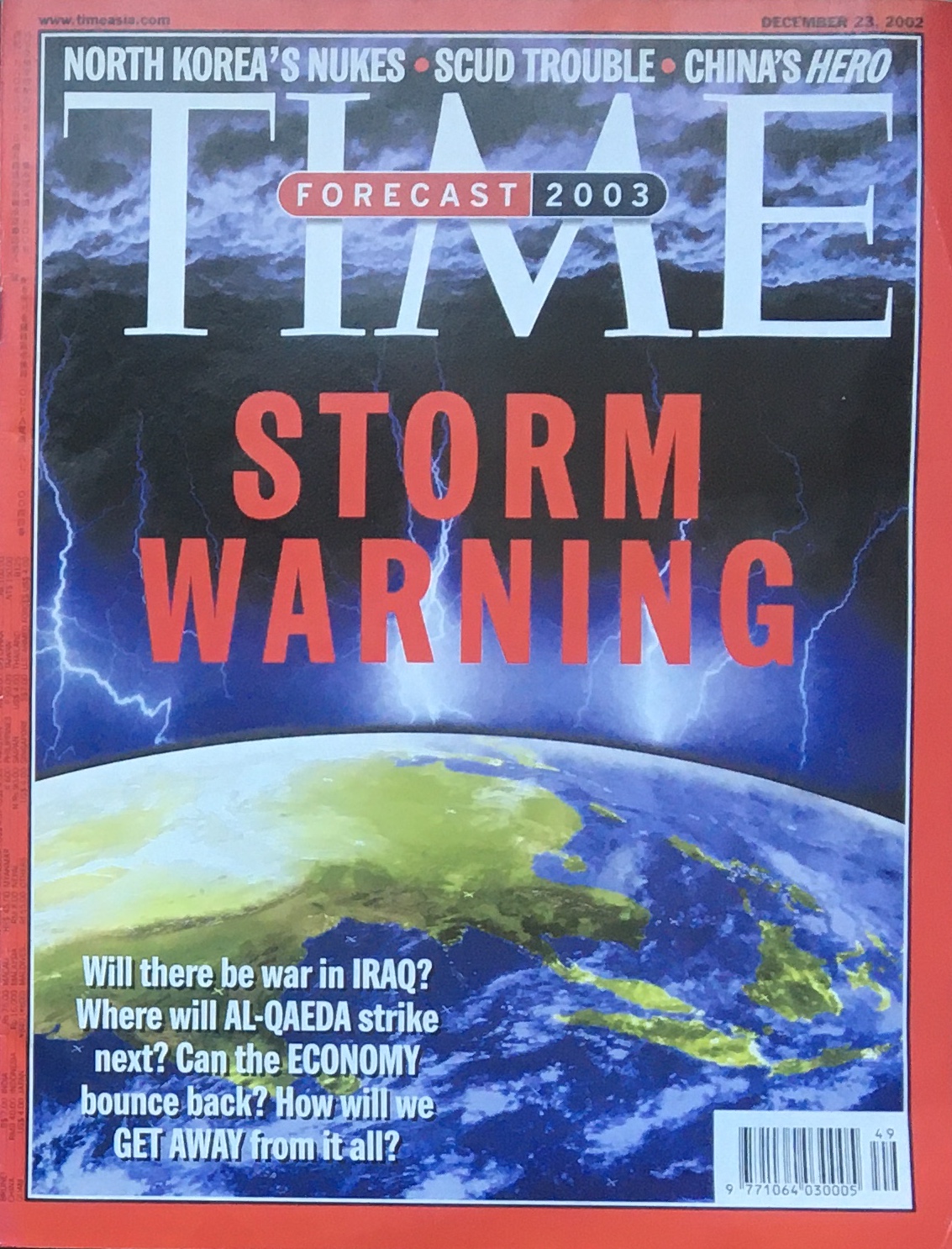

TIME Magazine Asia

by Kay Johnson