Action Asia

The Road Less Travelled

by David Espinosa

The Road Less Travelled

It was a brave conception, taking a motorcycle – with nothing but a pair of panniers strapped to the jump seat – some 500 km to the north of Hanoi, on ‘off-piste’ roads the likes of which few had ridden. Friends opined that it was more foolhardy than fun. I will admit I had only broadly conceptualised using a motorcycle as a means of exploring Vietnam; but the idea had merit. After all (and without sounding dramatic), what better way to penetrate the essence of a country than by the seat of my pants.

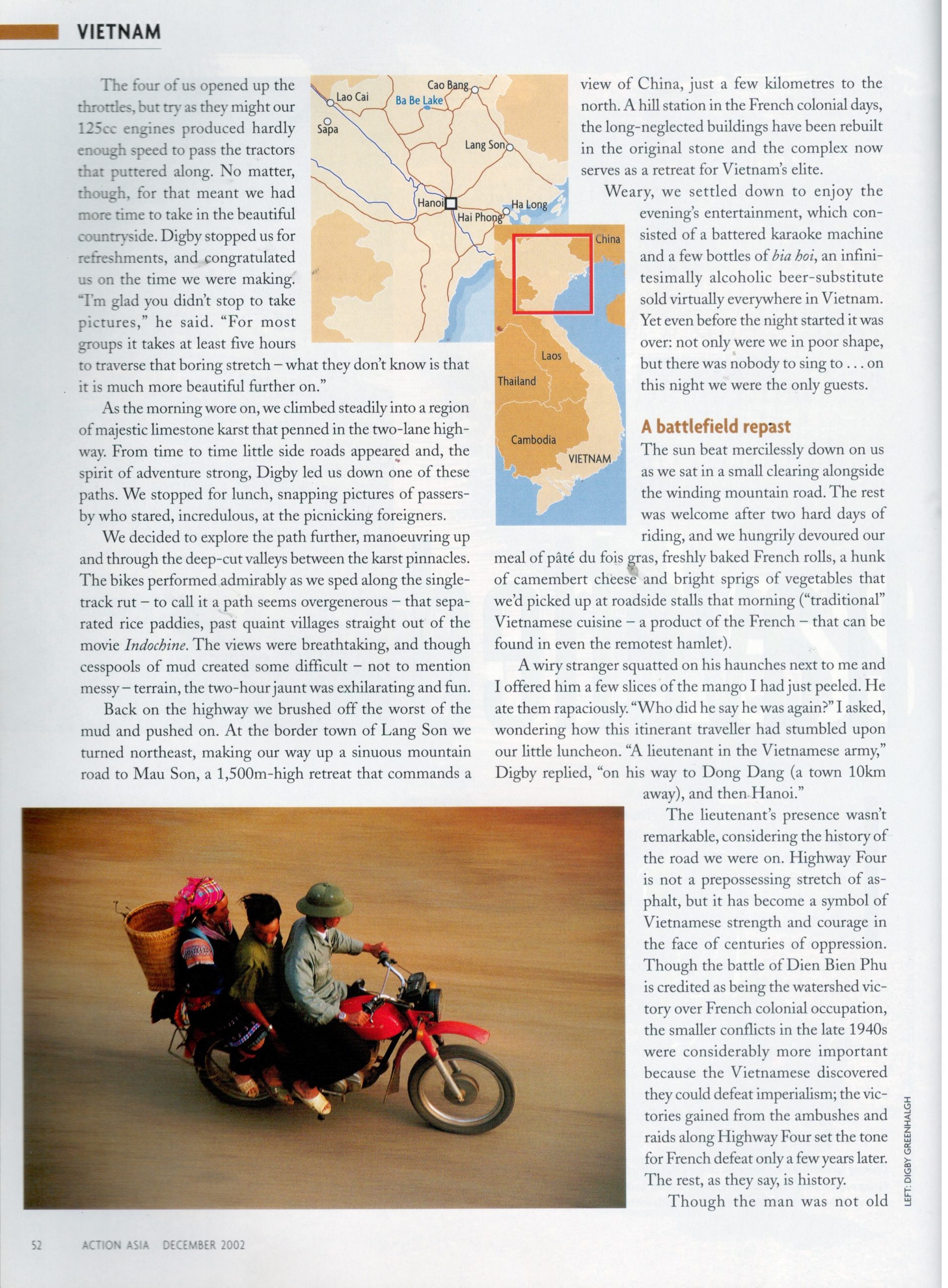

As peculiar as it may seem, a twin-stroke engine, with its horrific whine and purr, is in fact the perfect contrivance to explore ‘off the beaten track’ – in our case the border “roads” between northern Vietnam and southern China. The preferred chariot of northern Vietnamese is the Minsk 125cc, a small Russian bike that is virtually indestructible. The locals tend to modify theirs – for good or ill – or abuse them beyond recognition and mine, it seemed, had endured much the same: pieces of the body were stripped and rusted; the taillights were bent out of shape; the seat was cracked and peeling; and it looked as if it hadn’t been painted since the days of Kruschev.

Our point man defended the Minsk’s virtues. “It isn’t the prettiest of bikes,” he said with a touch of affection (and without so much as a smirk, I might add), “but it is terribly hardy.” He followed with an offhand remark that sent shivers up my spine, and reminded me of the potential folly of the trip: “You’ll be surprised the punishment they can take.” I soon discovered that what the Minsk lacks in comfort or good looks it more than makes up for in performance; and though it was a dubious thought, I had to put my trust in it for seven days along some of the toughest terrain in Vietnam.

The Road to Mau Son

The trip began auspiciously, for we embarked from the country’s distinguished capital, Hanoi. Volumes could be (and have been) written about the beauty of this stately city: its tree-lined, cobbled streets; the “tidy mess” of the Old and French Quarters; the nobility of the solitary lake around which so much is transacted; or of the people: the women pedalling ancient bikes, looking as if they were taken from another decade and the wiry old men, with long white beards – mirror-images of Ho Chi Minh – sitting in the doorsteps of the narrow French homes. But we needed to put some distance behind us on the first day, and so with a twinge of regret the three companions – Steve, Ian and I, sped past the chaotic activity to a highway that led us northeast.

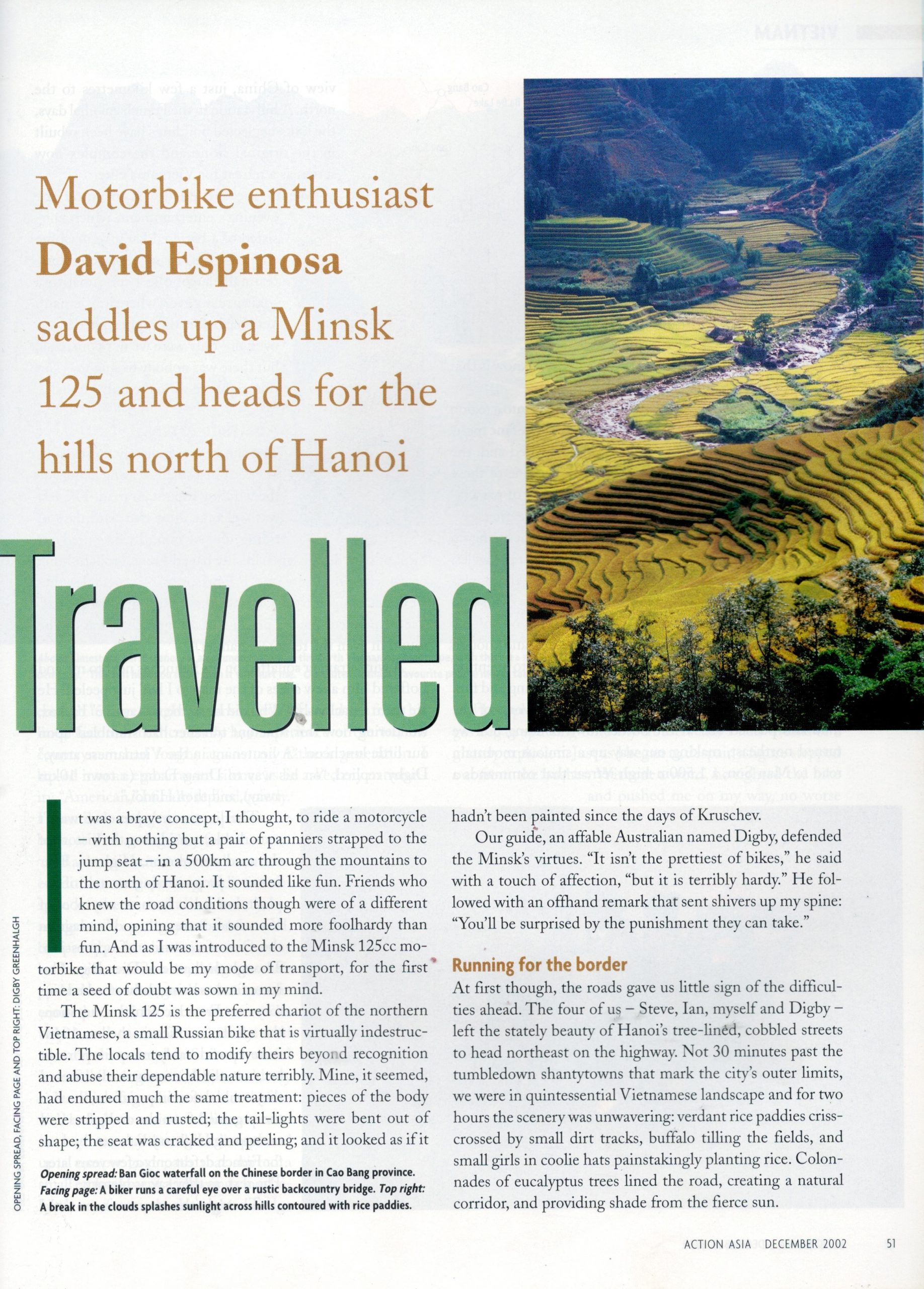

Not thirty minutes past the tumble down shantytowns that marked the city’s outer limits we began to encounter the quintessential Vietnam countryside. For two hours the scenery was unwavering: Spacious, verdant rice paddies were criss-crossed by small dirt tracks. Colonnades of eucalyptus trees lined major arteries, creating a natural hallway, and providing the sole shade for the tiny specks riding to and fro on bicycles. Oxen tilled the fields, and small girls wearing coolie hats and loose clothing painstakingly picked rice.

The three of us “opened up” the throttles, but try as it might the 125cc produced hardly enough speed to pass the tractors that puttered along. No matter, though, for we took in the refreshingly beautiful natural surroundings. Our guide stopped us for refreshments, and congratulated us on our speed. “I’m glad you didn’t stop to take pictures,” he deadpanned. “For most groups it takes at least five hours to traverse that boring stretch – what they don’t know is that it is much more beautiful further on.”

As the morning wore on, we began a steady uphill climb into a mountainous region. Surrounding us were majestic limestone karsts that penned in the two-lane highway; little roads sprang up from time to time, leading seemingly nowhere. The spirit of adventure strong, Our guide led us down one of these paths. We lunched in a glade, and snapped pictures of passers-by who stared, incredulous, at the white folks.

Back on the Highway

Our ham and Brie sandwiches digested, we decided to explore the path. The dirt track was walled in by those same karsts we saw from the highway, creating deep valleys that we manoeuvred up and through. The bikes performed admirably as we raced across the single-track rut (for to call it a path would be an insult to paths) that separated rice paddies, past quaint villages that looked as if they’d been taken straight from the movie Indochine. The views were breathtaking, and though cesspools of mud created some difficult – not to mention messy – terrain, the two-hour jaunt was refreshing.

Back on the highway we brushed off the dirt and mud, and pushed on. At the border town of Lang Son we turned northeast, traversing the quiet countryside before making our way up a sinuous road that cut deep into the mountains. The inexorable climb led us to Mau Son, a 1,500m-high mountain retreat that commands a view of China, just a few kilometres to the north. This small “resort” was once a hill station (read: brothel) in the French colonial days. The buildings had crumbled from neglect, but a local builder came in and rebuilt the original stone houses; the complex now serves as a retreat for Vietnam’s elite.

Weary, we settled down to enjoy the evening’s entertainment, which consisted of a battered karaoke machine and a few bottles of bia hoi, the infinitesimally alcoholic beer-substitute – perfect during or after a long day of riding – sold in virtually every home in Vietnam. Yet even before the night started it was over: not only were we in poor shape, but there was nobody to sing to…on this night we were the only guests.

A Battlefield Repast

The wiry figure next to me showed no discomfort as he squatted on his haunches in the ankle-high grass. The sun beat mercilessly down upon the five of us in the small clearing along the windy mountain road. The rest was welcome after two hard days of riding and, however unpleasant the conditions, we devoured our repast of pate du fois gras, freshly baked French rolls, a hunk of camembert cheese and bright sprigs of various vegetables that we’d picked up at roadside stalls that morning (“traditional” Vietnamese cuisine – a product of the French – that can be found in even the remotest hamlet).

Blood, Guts and Glory

In spite of its beauty, there is no lack of edge to Vietnam. And though the riding was tricky at times, the added danger was addictive. Our route was flexible, but proud (and stubborn) that we were no one was willing to back down. We pushed each other on: The more treacherous the road, in fact, the more we craved its twists and turns.

Late one day our little peloton disappeared up a narrow goat path that skirted a small embankment. Following close behind, my front wheel caught an edge and I toppled over, arms and legs akimbo. Bike and rider slid to a stop a few metres down; as gas began spurting onto my pants, I had visions of a ghastly explosion (admittedly, my imagination tends to get the better of me!). Just as I began to despair, a figure stepped out from the bushes. He righted the bike and pushed me on my way, no worse for wear save a mildly sprained ankle and a badly bruised ego.

Minor incidents reminded us of our own particular frailties, but it was much later we discovered Vietnam’s raw, unpredictable power. One morning we awoke to the crash and bang of heavy thunderstorms. Rain had flooded the riverbanks overnight; as proof of the storm’s might, a large pickup had become stranded in the middle of the raging waters. Ignoring the utter folly of riding in such harsh conditions, we set off after breakfast, mindful that we had to catch a ferry later in the day. We should never have left our beds…

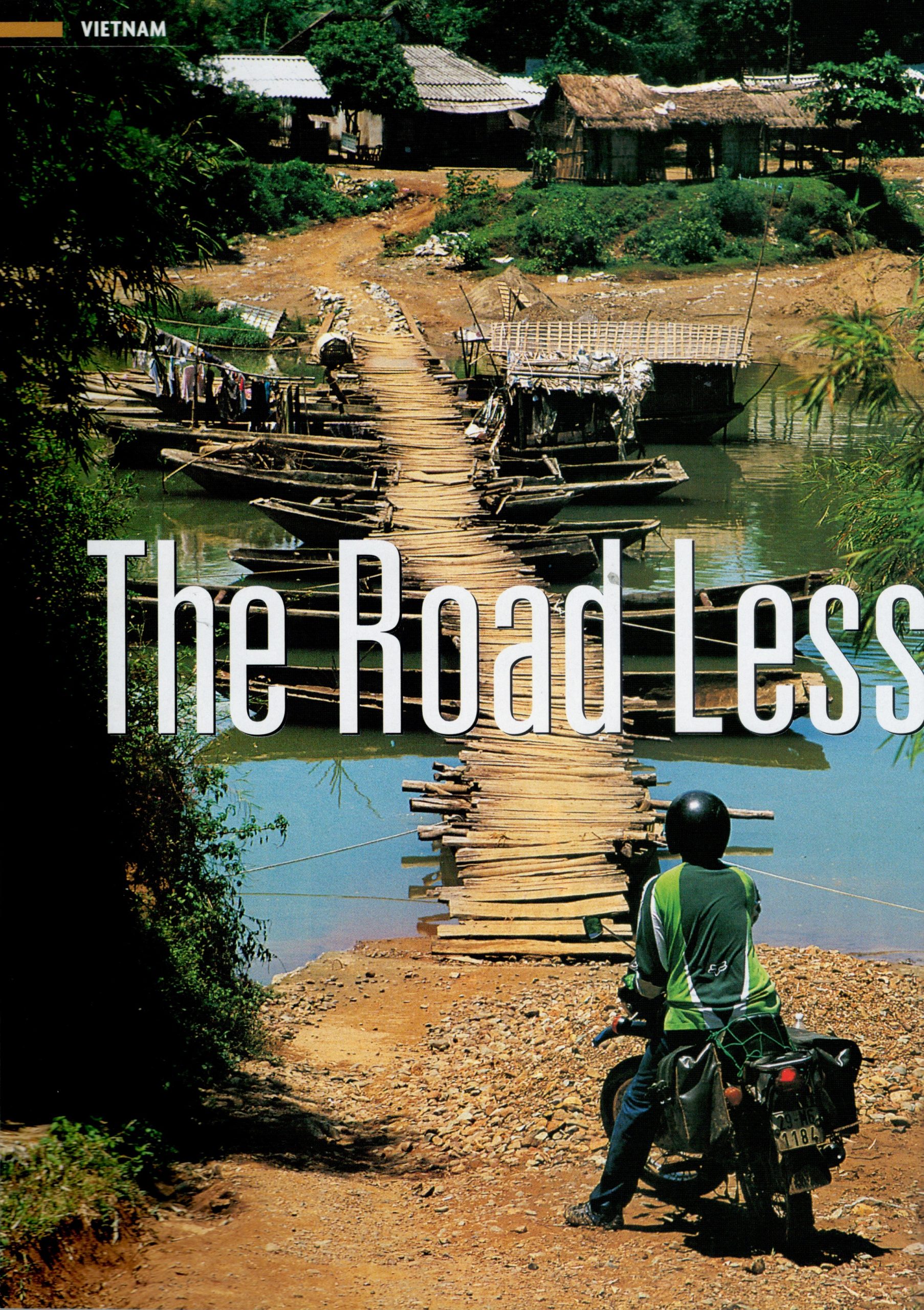

The day unfolded like some terrible nightmare. A few kilometres out of Cao Bang, we took a detour that would connect us to the Old French Road. The little party came upon a bridge “in progress” that spanned a slight stream; but the stream, after hours of heavy downpour, was now a fierce river. Despite Steve’s protestations, discretion got the better part of valour, and we unpacked, disassembled and carried the motorcycles over the portion of bridge that was finished.

In the face of more bridge crossings (one) and flat tires (two), we managed to reach a market town at the base of the Collye Pass Road. It was a gamble travelling along the remainder of this unfinished road, but it was our last hope to catch the ferry; the shortcut proved costly.

The Old French Road

Several partial avalanches and knee-deep mudslides checked our advance. Near the top, two diggers cleared a path through some of the more monstrous slides. Their work proved to be in vain, for 200 metres from the turn off to the Old French Road the road gave way, and a wave of rocks and boulders cascaded down in front of us.

The danger was palpable: the distinct “smell” of avalanches was in the air. Our progress had ground to a halt. Frustrated, we drove a few metres down the road to a small ledge, where we rested while the digger was called to clear a path. No sooner did we sit down then a second avalanche fell only metres behind us, effectively cutting our only path of retreat.

It was hours before we were able to continue, and we rode possessed down the Old French Road, which deserved a far more leisurely examination. For 60 kilometres we negotiated the potholed, uneven cobblestone path that had been built 100 years earlier by French engineers. The sun, which until now had been a rumour, broke through, and we raced past little brooks that trickled down the ivy-grown walls and heaven-sent glades redolent of exotic flowers.

It was hard going, but by early evening we managed to reach Cha Ra, a small town at the base of Ba Be Lake, only to learn that the road to our pick-up location had been flooded. Undaunted by the latest impediment, we were ferried across the new lake, past the tops of telephone poles, transformers and rows of rooftop terraces. As if actors in some farce, we then discovered that Ian’s tire had developed a slow leak – and once again we were forced to stop. Almost uncaring, we pressed on in the dark, through waist-deep waters which managed to swallow Steve’s panniers.

Finally, after nearly 14 hours of the most perilous roads imaginable we arrived at our lakeside chateau. Eschewing the good graces of our hosts I nearly dropped where I stood, and blissfully slept the night away.

Long Strange Trip

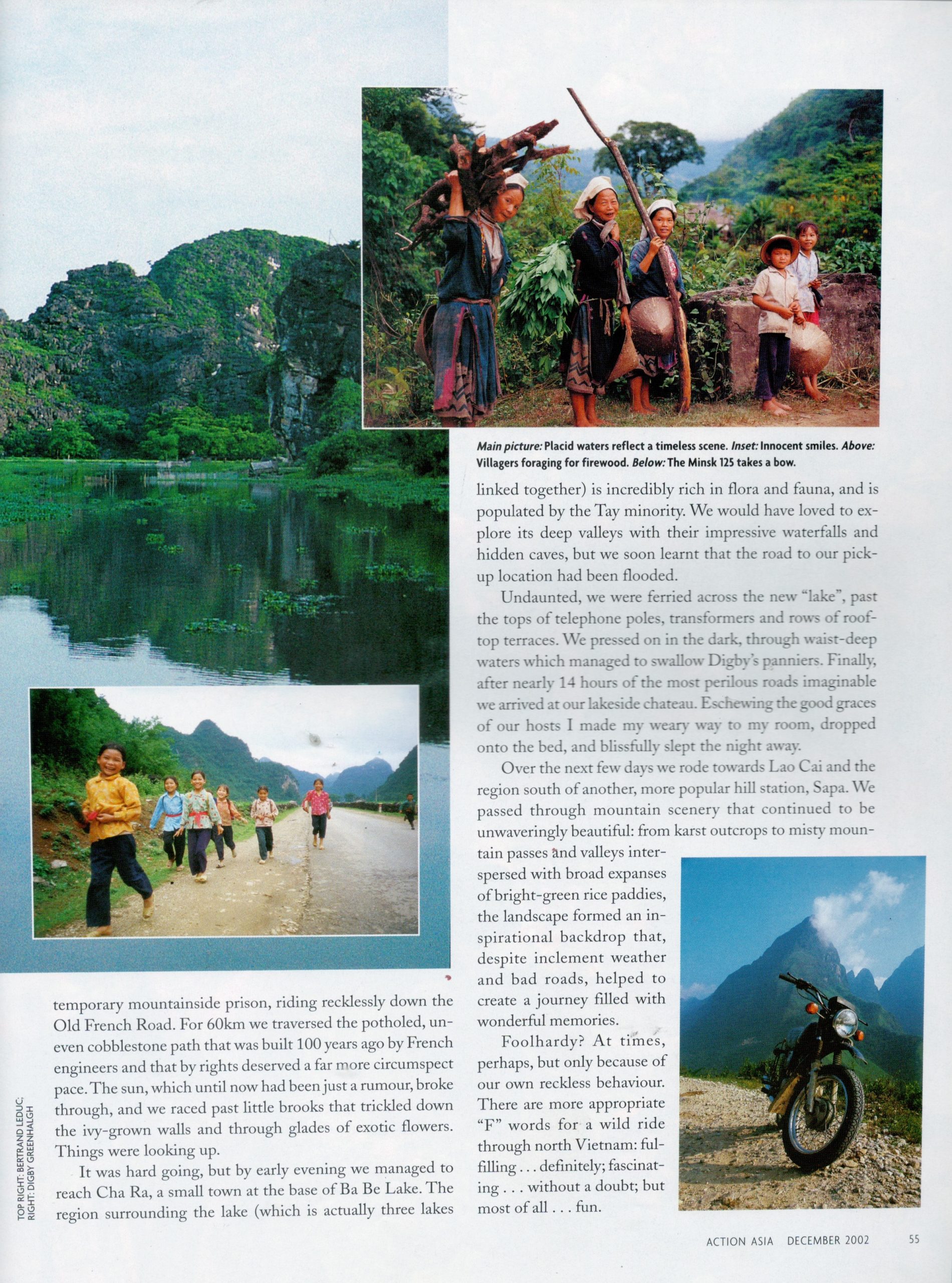

Bruised and battered, on the last day we rode through the mountainous region south of Sa Pa. The scenery was unwaveringly beautiful; and to top it off we encountered virtually all the more famous hill tribes – including the improbable Technicolor H’mong, wrapped in their gaudy cloaks.

Inclement weather, bad roads and Steve’s broken shoulder (suffered the week before the trip, lest you jump to conclusions) conspired to keep us from the more remote villages, but we had accomplished something absolute. And though I am prone to exaggeration, we were glad to have made it through intact. For us, our final destination was a disappointment; it was the journey that provided us with countless memories…not to mention the stuff of which tall tales are told.

More Articles

Two Wheels Magazine

by Digby Greenhalgh

Two Wheels

by Glenn Phillips

ADV Rider Magazine

by Sean Goldhawk